It’s been exciting to see the Science of Reading spreading over the past few years! The science of reading is a body of research investigating how children learn to read and which instructional approaches are most effective. The research spans over 50 years! This information has been there, but for some reason, it is just recently being translated into practice. Thanks to Emily Hanford’s articles and podcasts, this information is finally reaching teachers and school leaders.

Read this blog post to learn more about the Science of Reading.

For many of us, there was a pretty big shift in both mindset and practice that needed to be made. For me, this was a slow process over many, many years. However, I realize that for teachers who are new to the Science of Reading, there is both a desire and an urgency to make this switch quickly. This can feel so overwhelming because there is so much to learn! Like with most new things, it’s best to start by taking small steps and implementing manageable changes.

This post summarizes some of the things you can do to become a Science of Reading-aligned K-2 Classroom.

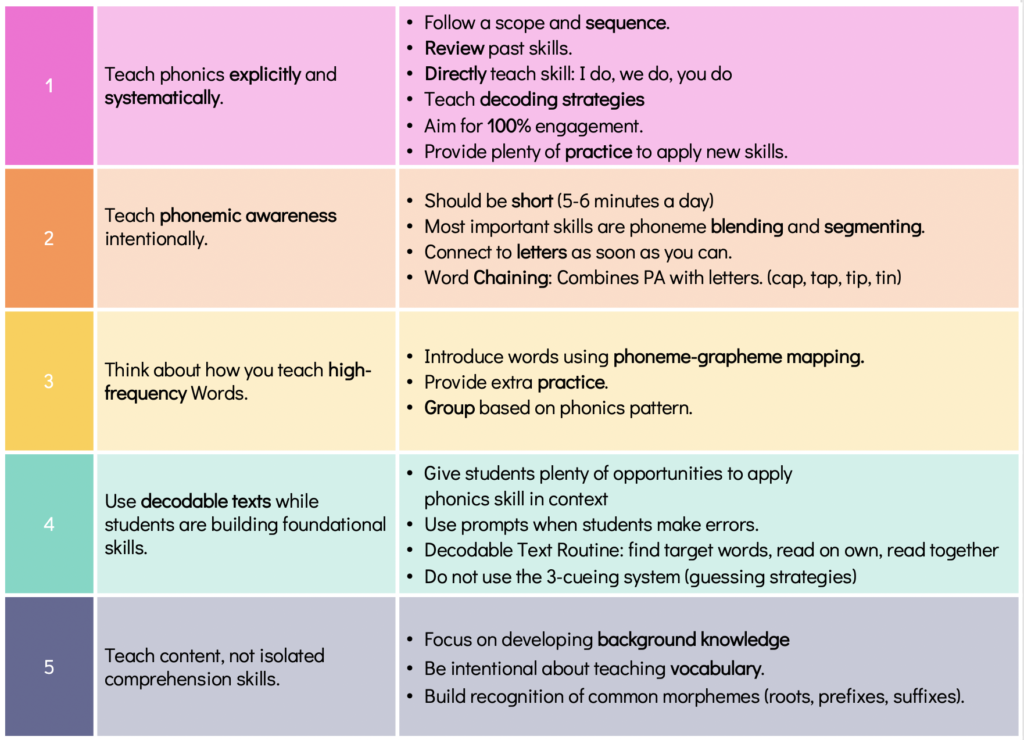

1. Teach Phonics and Morphology Explicitly and Systematically.

This is the first shift that I made. I became more direct and intentional with my phonics instruction. Below are some key elements of what it means to teach explicitly and systematically.

Scope and Sequence

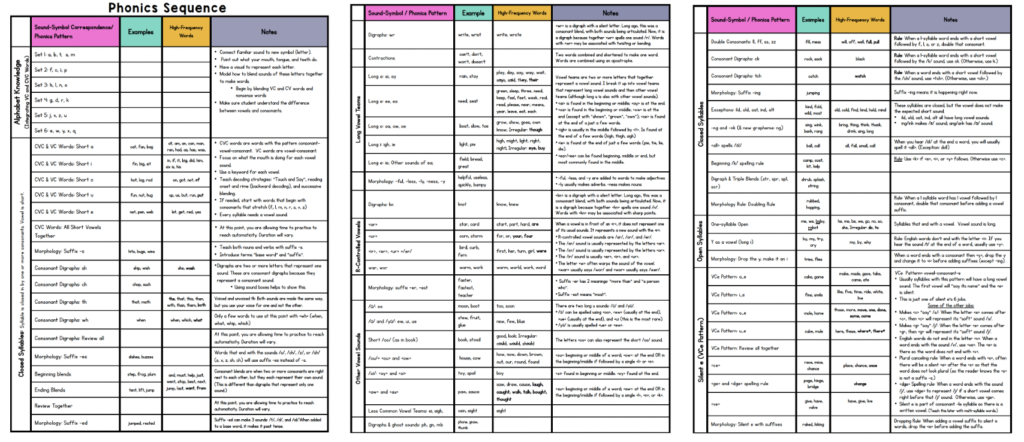

The first step is having a scope and sequence. A scope outlines the content and skills to be taught, providing a clear roadmap for what students need to learn at each stage. The sequence organizes this content in a logical order, building on previously learned skills and gradually increasing in complexity. This approach helps students develop foundational skills before moving on to more advanced concepts, ensuring that nothing is overlooked. There are several free options out there. You can find my free scope and sequence here. My scope and sequence includes the major phonics generalizations, too.

Establish a Routine

This resource lays out what a Structured Literacy lesson can look like.

Direct Teaching: I Do, You Do, We Do Approach

As you follow along the sequence, you will directly teach each skill. Using the “I do, We do, You do” approach is best. You explicitly teach the new skill and model (I do) for your students. Keep this part short. Introduce the new grapheme or phonics pattern and show some examples. Model decoding and spelling with that phonics element.

Next, you provide plenty of guided practice (we do). In my opinion, the guided practice can be the most powerful. During this time, your students are applying what you just taught them while you are providing guidance and as much support as they need. This can be in the form of leading questions, decoding together, or providing corrective feedback.

Finally, you will provide opportunities for independent practice (you do). This is so important because it’s this practice that solidifies the new learning. This can be partner work, centers, or seat work. While students get this independent practice, you could also work with a small group of students who need more guided practice.

If you are looking for an all-in-one resource to help you teach explicitly and sequentially, click here to check out my SoR Phonics Units.

You may also like this free resource to get you going!

Provide Opportunities to Apply Learning

Providing enough time for students to apply what they have learned is essential. Teaching the skill is just the first step. Giving our students ample practice applying that skill should be the bulk of the time. This practice comes in the form of decoding and encoding (spelling). Start with words, move on to phrases and sentences, and then passages/books (see below). I can’t emphasize enough how important practice is!

I think so often, we teach a new skill but then don’t give enough time to practice and apply this. This is especially important for students who have difficulty learning to read. They need a lot more practice, so be thinking about how and when you can provide that practice. I have seen teachers do a wonderful job teaching but then not provide that time for the students to apply and master what they just learned. I’ve been that teacher! So learn from my mistakes and really reflect on this one.

This resource here provides tons of practice reading and spelling words with all the phonics skills.

Teach Decoding and Encoding

Decoding helps students break down words into their individual sounds and blend them to read, while encoding strengthens their ability to spell by segmenting words into sounds and applying phonics knowledge. When we explicitly teach these skills and model the process, students gain the tools to tackle unfamiliar words with confidence.

For most students, I recommend using continuous blending. (I often call this “stretching sounds”.) Continuous blending is a powerful strategy for teaching beginning readers how to decode words smoothly and effectively. Instead of isolating each phoneme (sound) and then pausing before blending, students are encouraged to stretch out the sounds and connect them without breaks. For example, when decoding the word “map,” students would produce the sounds /mmmm-aaaaa-ppp/ in one fluid motion, rather than stopping between each sound. This technique reduces cognitive load, helping students maintain the sequence of sounds in memory as they form the word. Continuous blending also mimics natural speech patterns, making it easier for young learners to transition from sounding out words to reading fluently.

Another decoding strategy, successive blending, is great for students who are having difficulty with blending sounds.

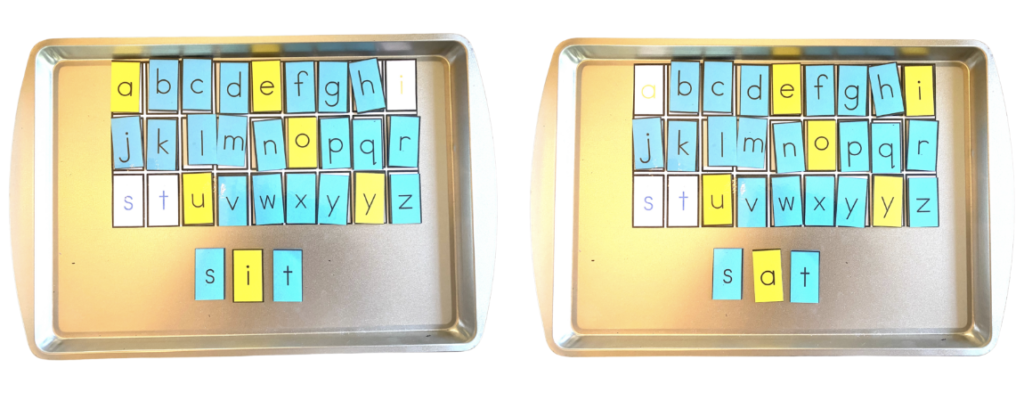

Encoding is such an important part of teaching literacy because it helps students connect the sounds they hear to the letters they write. Practicing encoding builds spelling skills, strengthens phonemic awareness, and helps students understand how words are put together. Using manipulatives like letter tiles, magnetic letters, or word cards can make encoding more hands-on and engaging for kids. For example, students can break a word like “cat” into its individual sounds and then build it by moving the tiles to match the sounds. This kind of practice helps make the process more concrete and gives students the confidence they need to grow as readers and writers. Click here for a post about using Sound Boxes.

100% Engagement

While teaching, we want to aim for 100% engagement. Make sure you provide enough think-time for your students. Give them whiteboards so they can all participate and show responses. Have students think-pair-share with a partner. I often have all students whisper-read words to themselves before we say the word out loud to the whole group.

Review Previously-Taught Skills and Concepts

Finally, make sure you weave in review of previously-learned skills. For example, if you are teaching silent e, make sure you weave in some short vowels in your decoding and spelling practice.

Learn Phonics Generalizations

Phonics generalizations are patterns or rules that help students decode and encode words. These generalizations provide students with a framework to tackle unfamiliar words. While not every rule applies universally, teaching these patterns equips students with strategies for reading and spelling with accuracy and confidence.

The science of reading emphasizes the importance of providing students with clear, consistent instruction based on how our brains process written language. Phonics generalizations, when taught systematically, fit into this approach by giving students the tools to apply their knowledge in meaningful ways. They work best when paired with plenty of practice, ensuring students can apply the generalizations they’ve learned to real reading and writing tasks.

While phonics generalizations can be helpful tools for teaching reading, it’s important to use them with balance and intention. Overloading students with too many rules at once can lead to cognitive overload, making it harder for them to apply what they’ve learned. Instead of focusing on memorizing every possible generalization, prioritize the most common and reliable patterns that will give students the greatest return in their reading and writing. The goal is to support their understanding of how words work, not overwhelm them with exceptions or rules that may not always apply.

Looking for visuals to guide you? These phonics posters may be helpful!

2. Be intentional about Phonemic Awareness

One of the most common sources of reading difficulty is poor phonemic awareness. The most important phonemic awareness skills are phoneme blending and segmenting, so these are the skills we want to focus on the most. An example of phoneme blending is saying sounds and asking a student to blend those sounds. For example, I would say /s/ /i/ /p/ and my student would blend those sounds to say “sip”. Phoneme Segmenting is the opposite. You say a whole word and your student breaks that word into its sound parts. For example, you would say “ship,” and your student would say /sh/ /i/ /p/.

Incorporate Letters

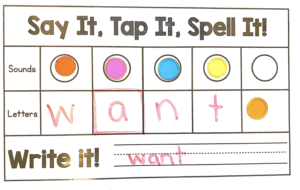

Although phonemic awareness is all about sounds, research has shown us that it is most impactful when we incorporate letters as soon as possible. This means that in kindergarten, we may begin doing phonemic awareness activities with just sounds, but after some time, when students have learned a few letters, we can start to practice phoneme blending and segmenting with those letters. For example, when students know the letters t, a, s, m, and b, you can start to show them how you can blend those sounds to make the words tab, sat, mat, at, and bat. Even though you are incorporating letters, our students are still working on the phonemic awareness skill of blending sounds. On the flip side, you can use those same words for spelling. This time, the phonemic awareness skill your students are practicing is segmenting sounds.

Read this blog post about how I start to merge phonemic awareness with my alphabet instruction as soon as possible!

Word Chaining

Word Chains are a great way to get students to blend, segment, and manipulate phonemes. A word chain (also known as a word ladder) is a list of words where each word changes only slightly, usually by just one sound.

Spelling (Encoding): Instruct your student to spell “sit”. Then, you will ask your student to change one letter to make “sap”. Students must first identify the sound that changed. Then, they need to figure out which letter to change. If you are not using letters, you would use bingo chips or cubes. In this case, you may ask the student to point to the chip/cube that changed its sound.

Decoding (Reading): Instruct your student to build or write the “sit”. Then, tell your student to change <i> to <a>. Now you ask your student to read the word. This is great because it provides practice reading words that are very similar. If you are not using letters, then you would having students orally segment “sit” ( /s/ /i/ /t/ ) as they push a bingo chip for each sound. Then, you would tell them to change /i/ to /a/ and ask them the new word. This is a high-level phonemic awareness skill.

You can find word chains here.

3. Rethink how you Teach High-frequency Words

High-frequency words are the words we see most often in texts. Most are “regular,” meaning their sounds and letters match up as expected. Some are “irregular”, meaning that at least one sound-symbol spelling is not expected. (For example, in the word “what”, the <a> represents the short u sound.) Read more about high-frequency words here.

We need to help our students move from decoding every word to recognizing words automatically. This automaticity leads to reading fluency. Focusing more on high-frequency words can be helpful.

When I first started teaching, I was trained to just ask students to memorize these high-frequency words. I was told that they were not decodable and didn’t make sense, so kids just had to memorize them. At one point, I even believed students could learn their shapes and, therefore, could read the words. Lists were sent home with parents and flashcards were overused. For a long time, some schools even taught “sight words” before all letters and sounds were mastered!

What Does the Science of Reading Say about High-Frequency Words?

- Research shows that readers store all words in their memory the same way, whether they are “irregular’ words or “regular” words. (Gough & Walsh, 1991; Lovett, 1987, Treiman & Baron, 1981) They pay attention to each letter in a word and then match them to the sounds they represent. Learning new words is not a visual process. We do not memorize words as whole chunks.

- Linnea Ehri created the term orthographic mapping to describe how the brain memorizes a word. A reader uses the part of the brain used for processing oral language to “map” the familiar sounds (phonemes) of words to the correct sequence of letters in the word. This process makes words instantly recognizable. Read more about orthographic mapping here.

- For a word to be truly “mapped,” the sounds, spelling, and meaning(s) of the word are all stored together. There are three distinct regions of the brain that are activated for this to happen. Because of this, we must teach in a way that activates all three parts.

- Although this process is essential for learning all words, focusing more on high-frequency words is helpful since our students will see those the most in texts.

Implications for Instruction

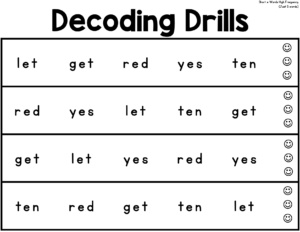

- Group high-frequency words by phonics skill: Because most high-frequency words are regular, you can teach them as you teach each phonics skill. For example, when you are working on CVC words teaching short e, you will teach the high-frequency words “get”, “let”, “red”, “ten” and “yes”. Instead of having a random list of high-frequency words, group these words by phonics skill.

- Weave into Practice: You will integrate the high-frequency words more into your decoding and encoding (spelling) practice. Here is an example of a Decoding Drill with high-frequency words. With this activity, students are focusing on short e, but getting repetition with the high-frequency words.

- 13 words account for 25% of the words in print (Johns, 1980): a, and, for, he, is, it, of, that, the, to, was, you. Since these words are so common, you will likely teach them earlier. For example, you will not wait until you teach r-controlled vowels to teach the word “are”. I always include it in my instruction with r-controlled vowels, but it gets introduced much earlier out of necessity.

- Use phoneme-grapheme mapping to introduce new high-frequency words (regular or irregular). Find directions here and mapping page here.

Find high-frequency word resources here and here.

4. Use Decodable Texts While Developing Foundational Skills

Decodable texts only (or mainly) contain the phonetic elements the student has already learned. They are also called phonetically-controlled texts. Students can use their phonics knowledge to decode unknown words when reading decodable books. Since the book is full of words using only the phonetic elements that they have been taught, students can be successful. They provide a structured and effective way to practice decoding, build reading fluency, and support overall reading development.

How to Integrate Decodable Texts into your Science of Reading Classroom?

When you teach a new skill (following your scope and sequence), you will give your students practice reading decodable texts that focus on that skill. That means that they will have lots of words that use that phonics pattern or grapheme. You can use decodable sentences, reading passages, or books.

For example, if you are focusing on digraph <sh>, you will give your students sentences, a passage, or a book filled with words with <sh>. However, it is important that this text mainly uses previously-taught phonetic elements as well. That means this text will not have vowel teams, silent e, or r-controlled words. It will only have short vowels.

Want to check one out? Here are four free decodable passages for digraphs.

Want to learn more about decodable texts? Click here for that blog post. I share my favorite publishers!

Want more decodable texts? Click here for decodable books, here for decodable passages, and here for decodable sentences.

5. Teach Content, not Isolated Comprehension Skills

I was taught originally that comprehension was developed through the teaching of isolated skills. I would choose a skill and practice that for a week. The Science of Reading shows up that the best way to improve reading comprehension is through knowledge building. Having background knowledge about the topic you are reading makes everything more accessible.

So what does this mean for instruction? We should spend more time focusing on science and social studies content. Choose texts that focus on a particular science or social studies topic. This can include both narrative and informational texts. Reading multiple texts on the same topic helps students build a deeper understanding and broader knowledge base.

This also allows you to revisit key vocabulary that may be used over multiple texts. Explicitly teach vocabulary related to these topics. Make connections between vocabulary words and the overall topic. Continually review the vocabulary over time.

In this recent study, researchers found that no single reading comprehension strategy works best in isolation. Instead, the combination of teaching the main idea, text structure, and retelling strategies proves to be the most effective in improving reading comprehension. These strategies should be paired with background knowledge instruction to ensure their effectiveness. Having background knowledge helps reduce the cognitive load.

Incorporating the science of reading into your classroom doesn’t have to be overwhelming. Do what you can and make changes at a pace that works for you. The best thing you can do is educate yourself about how the brain learns to read. From there, you can take some of these steps.

Update: I created this visual to post on Instagram, but then realized it may be a helpful poster to print out and post as inspiration. Each square has a recommencation of something to start doing and something to swap out. Click here to download this printable.