This blog post goes into my interpretation of Structured Literacy and how I have applied it to my classroom and tutoring. I do not consider myself an expert, just sharing what I’ve learned/what I’m still learning.

Update: I’ve had some requests for these slides, so I am sharing the PDF and slides here.

What is Structured Literacy?

Structured Literacy is an instructional approach to teaching students to read that encompasses all of the elements of language and has key principles that guide how it is taught. It emphasizes explicit, systematic teaching of the structure of the English language. Research has shown that it is effective for all students and essential for students with dyslexia.

The International Dyslexia Association came up with this “umbrella term” to unify popular methods, such as Orton Gillingham, Explicit Phonics, and Multisensory Structured Language. I have been studying Structured Literacy, applying it to my reading instruction, and reflecting on its effectiveness for a few years now. I wanted to form my own opinion based on experience before writing this post. I have to say, I am a believer! (Scroll down to learn more about dyslexia.)

How to Teach the Elements of Structured Literacy

Structured Literacy isn’t just about what we teach—it’s also about how we teach it. These key principles guide instruction, ensuring students get the support they need to become confident readers.

These guiding principles of Structured Literacy have helped me so much. This was the first thing I changed. I became very reflective about how I was teaching my students.

Here are some things I changed to do this:

- I now have a clear sequence.

- I always review concepts before introducing new ones.

- I teach each new concept in a direct way and then allow for plenty of opportunities for my students to practice in a guided setting.

- I build on lessons previously taught, meaning I never ask students to read or spell words with things I have not taught them yet.

- For example, if I’m teaching digraphs I will not include words like “shark” or “beach” in their reading or spelling work because I have not taught bossy r or vowels at that point yet. At that point, I would have taught CVC words, so the reading and spelling consist of CVC words and words with digraphs and short vowels only.

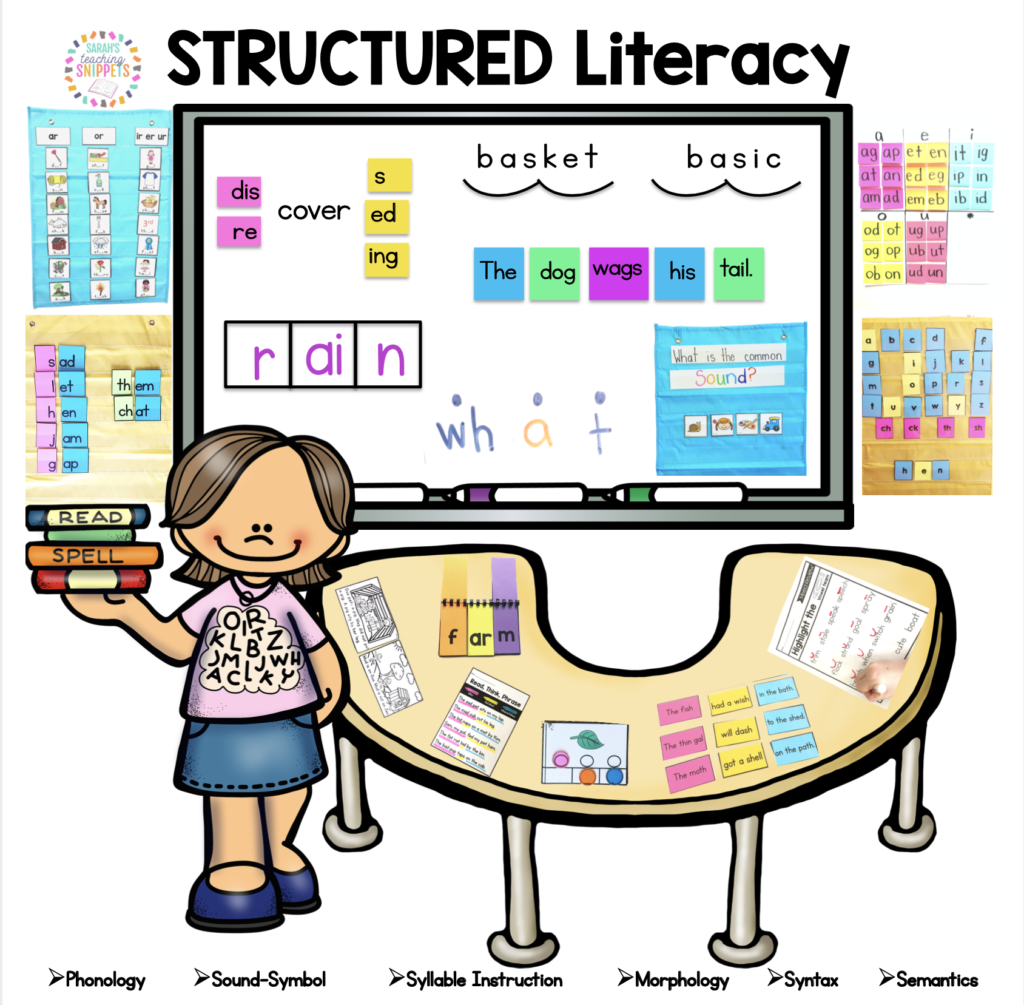

Components of Structured Literacy: What to Teach

Structured Literacy encompasses several critical elements that work together to build a strong foundation in reading and writing:

- Phonology: The study of sound structures in spoken words. English comprises 44 phonemes, and understanding these sounds is crucial for decoding words.

- Sound-Symbol Association: Connecting sounds (phonemes) with their corresponding letters or letter combinations (graphemes).

- Morphology: The study of word parts that carry meaning, such as roots, prefixes, and suffixes.

- Syntax: The set of rules that dictate sentence structure and word order.

- Semantics: The meaning of words and sentences.

Each part plays a key role in helping students become strong readers, and bringing them together gives kids a deeper understanding of how language works. Let’s take a closer look at each.

Phonology

Phonology is the study of the patterns of sounds. The first step for our readers starts long before they pick up a book or a pencil. I always like to say, “Learning to read begins with our ears.”

Phonological awareness is the ability to recognize that spoken words are made up of sound parts. Phonological awareness skills include sentence segmenting (identifying words in a sentence), rhyming, alliteration, and identifying syllables. The most advanced phonological awareness skill is phonemic awareness.

Phonemic awareness is the awareness of individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words and the ability to manipulate those sounds. When a student has phonemic awareness, they can take a whole word like “bat” and orally break it up into its speech sounds (/b/ /a/ /t/). They can also do the opposite and blend together individual speech sounds to say a word. These are the skills required for decoding and spelling.

Strong phoneme awareness in kindergarten can be an indicator of reading success later on. Explicit teaching of phonemic awareness can provide a strong foundation for reading and spelling. Students with dyslexia often need intervention with phoneme awareness early on in kindergarten and will continue to need more intervention with advanced phoneme manipulation in later years.

Sound-Symbol Correspondences

Sound-symbol awareness is the understanding that letters and letter combinations represent (or spell) spoken sounds. This foundational skill helps students grasp that print is not random—there is a system to how letters map to sounds, which allows for decoding (reading) and encoding (spelling).

Helpful Terms & Knowledge for Understanding Sound-Symbol Awareness

Phonemes are individual speech sounds. English has 44 phonemes.

Graphemes are the letters or letter combinations (like ea, igh, th) that represent sounds in written words.

- A single grapheme can represent more than one sound. For example, ea can sound like /ē/ in eat or /ĕ/ in bread.

- A single sound can be spelled with different graphemes. For example, the long /ē/ sound can be spelled as ee (see), ea (tea), ie (field), or ey (key).

To become proficient readers and spellers, students need explicit and systematic instruction in sound-symbol relationships. They must learn to match phonemes (spoken sounds) to graphemes (printed letters) and apply this knowledge in both reading and spelling. Sound-Symbol association must be taught and practiced in two ways:

- Visual to Auditory: When reading, students must translate written symbols into sounds and blend them to form words.

- Auditory to Visual: When spelling, they need to segment words into individual sounds and convert those sounds into print.

How to Teach Sound-Symbol Correspondences

Now let’s connect the what with the how.

- What:

- Sound-Symbol Relationships (Teach graphemes that spell sounds.)

- Teach “rules” or patterns (for example, <ck> is only used at the end of words following a short vowel)

- How:

- Use a Scope and Sequence that guides you from the simplest graphemes to the more complex. Following a scope and sequence ensures that you don’t miss anything.

- Be direct when introducing a new grapheme or “rule.”

- Use routines that are backed by research (teach decoding strategies, practice spelling using phoneme-grapheme mapping, provide practice using decodable texts)

- An example is shown below:

Syllable Instruction

Another important component of Structured Literacy is syllable instruction. Understanding syllables is essential for both reading (decoding) and spelling (encoding) because it helps students break words into manageable parts and apply consistent patterns to unfamiliar words.

A syllable is a unit of spoken language that contains one vowel sound. While spoken syllables do not always match neatly with written syllables, written syllables follow predictable patterns that can help students decode and spell words accurately.

Syllable Types

There are six common syllable types in English (closed, open, silent e, vowel team, r-controlled, and consonant-le), and teaching these syllable types explicitly helps students recognize patterns in words and apply consistent decoding and spelling strategies. By knowing the syllable type, readers can determine the vowel sound. And as I like to tell my students, “It’s all about the vowels!”

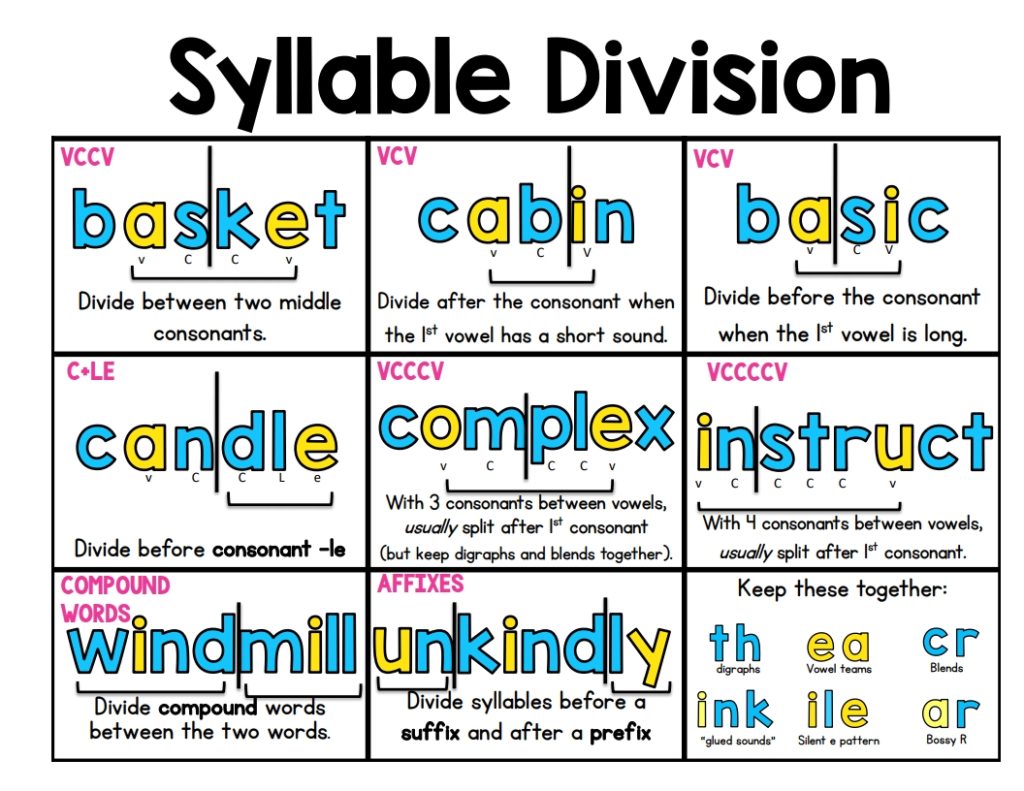

Syllable Division

Once students understand syllable types, the next step is learning syllable division patterns for multi-syllabic words. Syllable division patterns show students how to break words into syllables when reading and spelling. Knowing where to divide words can help students decode unfamiliar words accurately.

There are several common syllable division patterns in English:

- VC/CV (Vowel-Consonant/Consonant-Vowel) – Divide between the consonants

- Example: rab-bit, nap-kin, bas-ket

- VCV (Vowel-Consonant-Vowel): This has two different options.

- V-CV – Divide before the consonant to create an open syllable

- Example: mu-sic, ro-bot, ti-ger

- VC/V – Divide after the consonant to keep the first syllable closed

- Example: lem-on, fin-ish, clos-et

- V-CV – Divide before the consonant to create an open syllable

- VC/CCV – Divide after the first consonant.

- Example: os-trich, con-tract

- Consonant-le (C-le) – Divide before the consonant-le syllable

- Example: ta-ble, lit-tle, sam-ple

- The consonant-le syllable is always at the end of the word and must be attached to the preceding syllable.

- V/V (Vowel-Vowel) – Divide between two vowels that do not form a vowel team

- Example: di-et, li-on, flu-id

- This pattern occurs when two vowels are next to each other but represent separate sounds.

Morphology

Morphology is the study of meaningful units of language and how they are combined to form words. These meaningful units are called morphemes. Morphemes are the smallest unit of meaning. This means you cannot break that word part down any further and still have meaning. Morphemes include prefixes, suffixes, and bases.

Every word either is a base has a base with one more morphemes added to it. The base holds the main meaning of the word. Prefixes are attached before the base and suffixes are attached after the base.

The tricky part about English spelling is that while morphemes tend to stay consistent in spelling, their pronunciation can change depending on the word they appear in. This is why, as students advance in reading and spelling, morphology becomes just as important—if not more important—than phonology.

For example, take the word please. The base <please> contains the grapheme ea, which represents the long e sound (/ē/). However, when we add -ure to form pleasure or -ant to form pleasant, the pronunciation shifts—the ea now represents the short e sound (/ĕ/), but the spelling remains the same.

This happens because English spelling prioritizes preserving the structure of words over perfectly representing pronunciation. That’s why, once students build a strong foundation in phonology (understanding sounds and their spellings), they need to shift their focus to morphology—learning how word parts function and how they can change a word’s meaning or pronunciation. This concept is key to understanding why English spelling may seem inconsistent at first glance—but in reality, it follows predictable patterns based on meaning rather than just sound.

Teaching morphology helps students recognize that words with the same base often share spelling patterns, even when their sounds shift. Studying these word families can help with spelling and vocabulary! Studying morphology can even help us understand why some seemingly irregular words are spelled the way they are! (The image below shows the word family for “do”. It illustrates that “does” is just the base “do” + suffix -es. The pronunciation is a bit off, but the spelling totally makes sense when thinking about the structure of the word.

And when we study one base, we unlock so. many. words. It’s an efficient and effective way to develop vocabulary, master spelling, and improve decoding!

If you are interested in learning more about morphology, check out these three posts:

Syntax

The IDA defines syntax as the system for ordering words in sentences so that meaning can be communicated.

Syntax refers to the rules that govern sentence structure—how words and phrases are arranged to form grammatically correct and meaningful sentences. While phonology and morphology focus on individual words, syntax helps students understand how those words fit together to form sentences.

Syntax and Reading Comprehension

Syntax is hugely important to comprehension.Many struggling readers can decode words but still struggle to understand full sentences. That’s often a syntax issue rather than a phonics issue. Teaching students to recognize sentence structures—like how dependent and independent clauses function—helps them break down long or complex sentences into manageable parts.

Where to Start?

Since syntax is such a broad area, it helps to start with foundational skills and build from there.

I have a lot to learn about syntax still, but there are a few activities that my students and I both love!

Sentence scramblers are an activity where students are given words in a mixed-up order, and they must rearrange them to form a complete, grammatically correct sentence.

I align this to my phonics instruction in the early grades. For example, if we are working on silent e, I will make a decodable sentence with silent e words (and any other phonics pattern we have already worked on) and turn that into my sentence scrambler.

You can extend this by identifying nouns, verbs, and adjectives. You can also break the word into subject, action, and additional phrases (like “into the cold lake”.

This activity helps students develop syntax awareness, sentence structure skills, and fluency.

Find pre-made Sentence Scramblers here.

Build a Sentence: I do this with both phrases and words. Students mix and match to build different sentences.

For kindergarten and first grade, you can read decodable words and sort them into nouns (who/what) and verbs (action/doing). Point out that sentences need both a “who” and a “do”. Then use those cards to build simple sentences. (Add in the word “the”, suffix -s, and punctuation.) Extend this by adding prepositional phrases that show where.

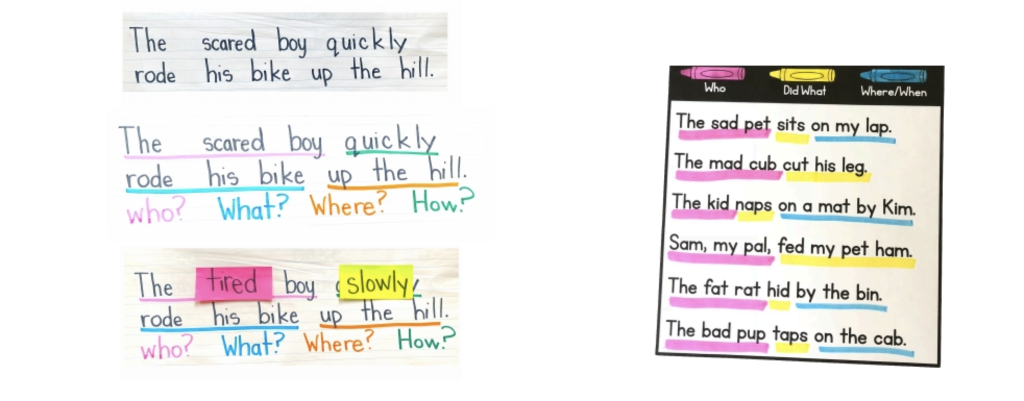

Find Phrase Building here (picture on the left) and Build a Sentence here and here. (picture on the right).

Looking at parts of a sentence: You can ask questions that encourage students to look at the parts of a sentence.

- Who or What is this sentence about?

- What did they do?

- How was it done?

- Which word or phrase told you that?

- Where or when?

Pictured on the left: Change up Adjectives and Adverbs: Write a sentence. Ask the questions above. Change an adverb or adjective and discuss how it changed the meaning of the sentence.

Pictured on the right: Read the sentences. Then, break up sentences by identifying the different parts. Find this activity here.

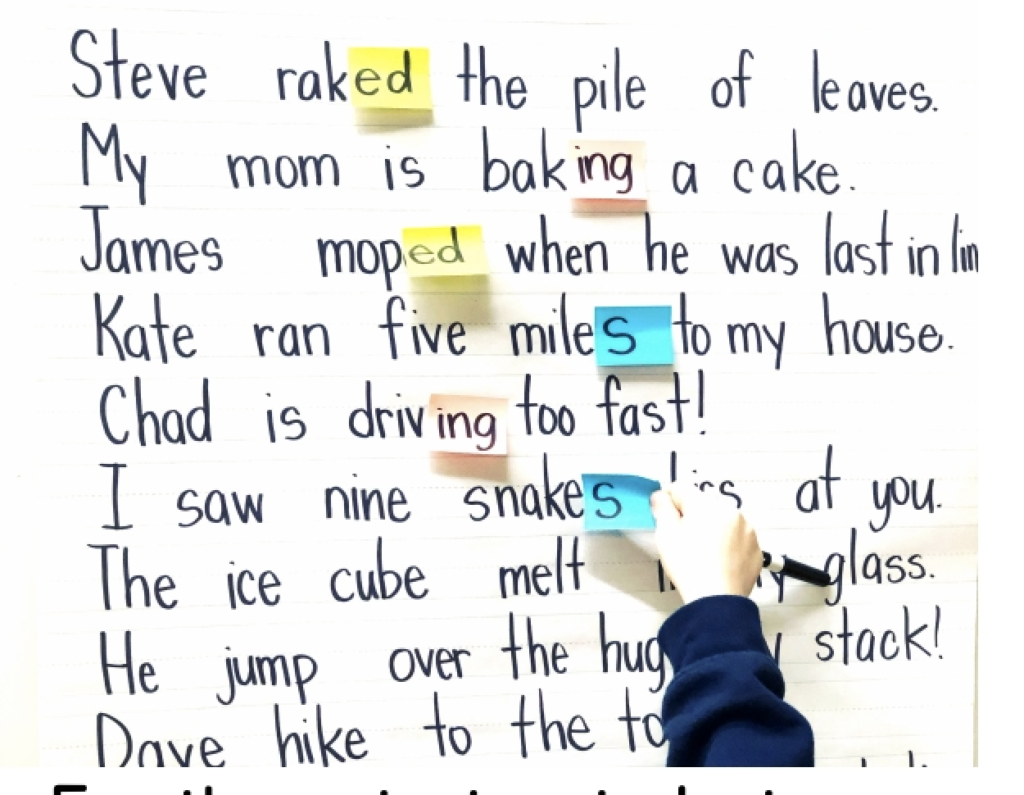

For the activity shown below, students are reading the sentence, then choosing the correct inflectional ending to add to the words.

Semantics

When we talk about semantics, we are referring to finding meaning in language. In teaching, we usually refer to it as comprehension.

I love both of those comics because they illustrate how context and background knowledge affect our understanding of words and concepts.

It is important to note that you do not need to wait when it comes to comprehension instruction. In other words, a child does not need to be able to read in order to develop comprehension skills. Reading comprehension is a result of word recognition and language comprehension (this is the Simple View of Reading).

- Language comprehension literally begins before kids enter school. We can continue to improve language comprehension through read-aloud. A child can benefit so much from read-alouds that are intentional. In the younger grades, we can need to focus on vocabulary development and building background knowledge.

- Word Recognition comes from all of those other elements above (phonemic awareness, phonics, sound-symbol association, and morphology).

Here is my understanding of what semantics entails:

The IDA says: Comprehension of both oral and written language is developed by teaching word meanings (vocabulary), interpretation of phrases and sentences, and understanding of text organization.

Semantics includes understanding…

- Meaning of individual words (vocabulary) and morphemes.

- How words are related .

- How the arrangement of words in phrases and sentences impacts the meaning of the word.

- How using context can help determine meaning of a word

- Idioms, synonyms, antonyms, categories, metaphors, and semantic gradients (shades of meaning).

- Denotation (dictionary definition) and connotation (cultural and contextual definition)

I found this in my studies and thought it was super interesting. I ordered the book so I’ll hopefully have a better understanding soon! Notice how the symbol cannot directly go to the referent. We must have conceptual understanding first (for a cat, that might be fury, pet, mammal, tail, cuddly, whiskers).

Below is s an example of a quick and easy word web. The question was about the word sanitary, which was used in a book. I compared it to “clean”, then we came up with synonyms for clean. Next, we sorted them into two categories. One side has more to do with “healthy” cleaning, and the other to do more with “neat” cleaning.

Why Structured Literacy

Research shows that Structured Literacy works for all students—and it’s critical for those with dyslexia. Unlike Balanced Literacy, which often doesn’t provide enough focus on word analysis and decoding, Structured Literacy gives students the tools they need to truly understand how words work.

One more reason? During the last few decades, cognitive scientists and researchers have done thousands of studies about how skilled reading works, what children need to be able to do it, and why some children struggle with reading. The elements and guiding principles of Structured Literacy are based on this science.

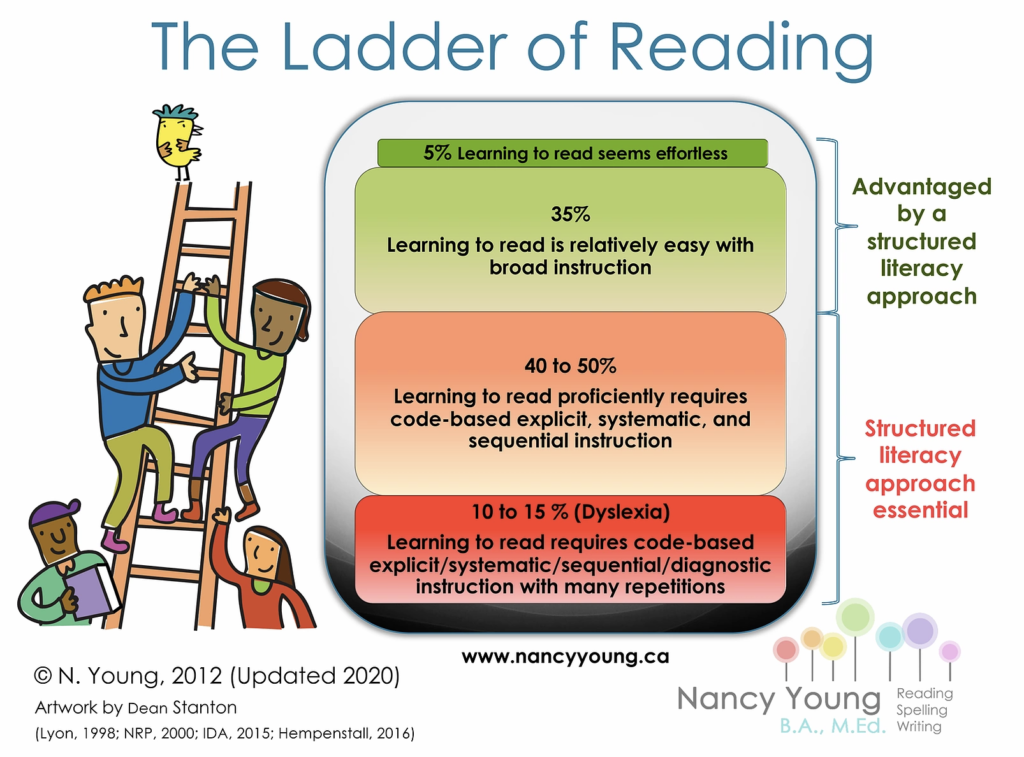

The Ladder of Reading

This infographic is such a powerful visual! It was created by Nancy Young, a member of the International Dyslexia Association, and every time I see it, I think of the first-grade classes I’ve taught. It just makes sense.

There are always a handful of kids who seem to teach themselves to read, picking it up with little to no instruction. Then you have the ones who catch on quickly and keep progressing with minimal effort. Others get there, but they have to work at it. And then there’s that 10-15%—the kids who struggle no matter how much we support them, leaving us wondering what’s missing.

The Ladder of Reading helps explain why. It shows that while reading comes easily to some, the majority of students need explicit, systematic instruction—and for those who struggle, Structured Literacy isn’t just helpful, it’s essential.

Used with Nancy Young’s permission. Click here to visit Nancy Young’s website to learn more.

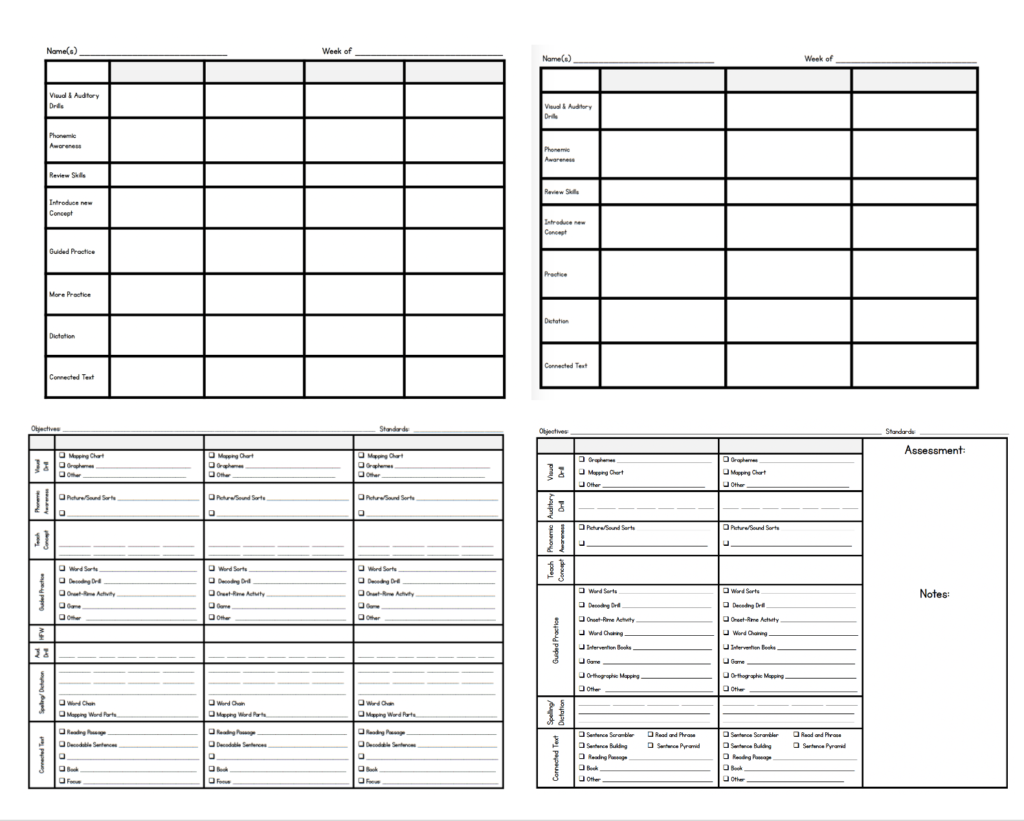

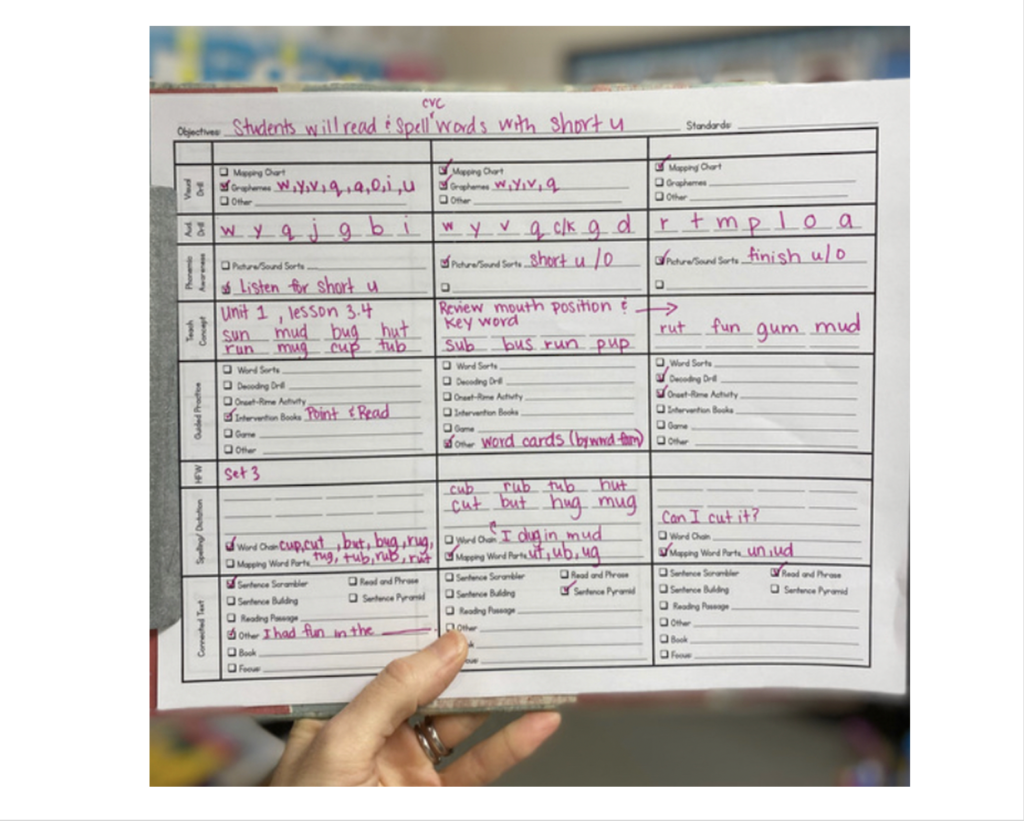

Lesson Plan Templates for Structured Literacy

Click here for editable lesson plan templates.

Here are the components of a lesson. When I’m teaching small groups, I don’t get to every section every day or I spend a different amount of time on each. For example, on the first day of teaching a particular skill, I may spend more time teaching the concept, doing guided practice, and spelling words. Then, the next day, I’ll spend more time on guided practice, applying to a connected text, and spelling/dictation. One thing I’ve learned is that you don’t need to spend a ton of time teaching. We want to make sure that we give students plenty of time to apply their new learning, especially with connected text .

Here are examples of activities I would do in each section.

Where to Learn More

Update: Here are some places to learn more.

- Science of Reading Info.com and this Facebook group

- The podcast Amplify and the Teaching, Reading and Learning are amazing! You will learn so much about the classroom application of the science of reading here.

- UFLI is another great resource!

- Reading Teachers Toolbox

- If you’re not sold on the why, check out Emily Hanford’s report

- I highly recommend looking into LETRS training.

Other Related Blog Posts

To learn about Reading and the Brain, click here

To read posts about dyslexia, click here.