Hi everyone! This post has been a LONG time coming. The more I learn about reading and the brain, the more hungry I get for even more information! I keep hearing experts say “reading is rocket science”. I completely agree! Understanding the “science of reading” has transformed the way I teach.

This post is part of a series that I’m doing about dyslexia. Make sure you check out the other posts about dyslexia here. This post doesn’t quite dive into dyslexia, but it sure does set the stage! This is all about how our brain reads. I find this all SO fascinating!

Before I go any further, I have to say a little disclaimer: I am not a brain scientist. I do not have a PHD or anything like that. This comes from several years of reading articles and books, taking online classes and other pd workshops on the topic. I am slightly obsessed with the topic of dyslexia, but I don’t feel like I can call myself an expert. I do feel like it is SO important to share the knowledge that I do have.

After reading this post and my other posts about dyslexia, I encourage you to keep learning and start making adjustments to your teaching so you can meet the needs of students with dyslexia (which happen to be 1 in 5.) I’m STILL making these adjustments, learning, and trying to meet the needs of these students. It’s not easy, but I feel like it’s so important to at least get this dialogue started (or continue it if you’ve already started) so we can make positive changes together. Okay, my little speech is over and now to the good stuff! 🙂

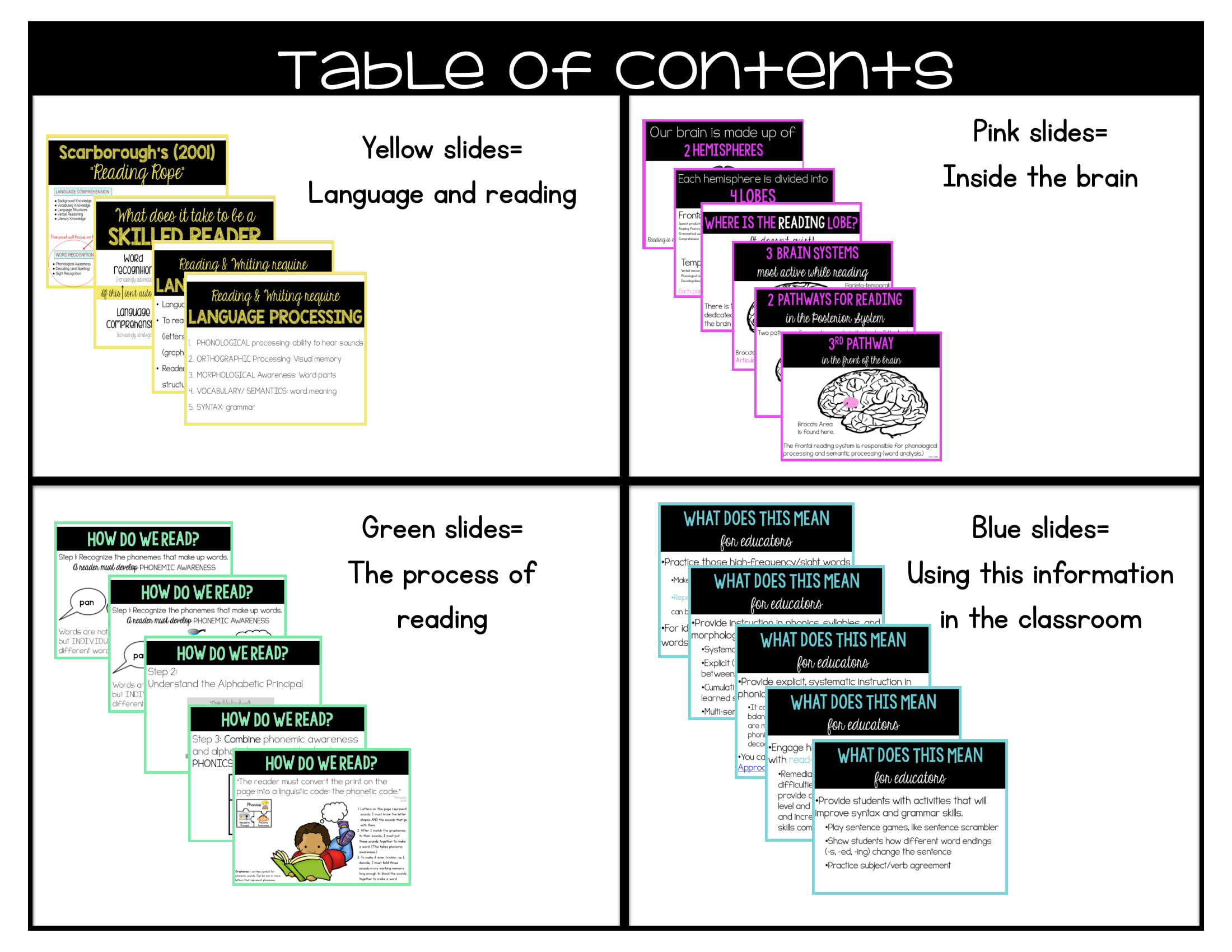

Since this blog post is SO long and has so much information, I’ve made a little “key” to help organize all this.

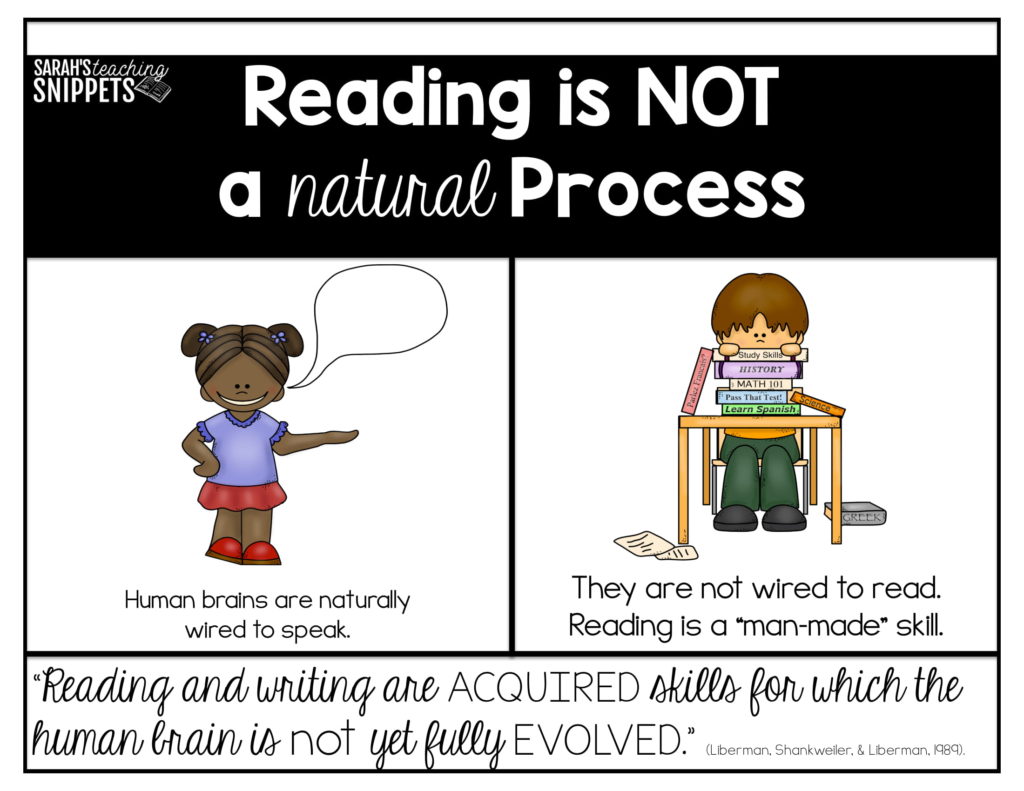

I think it’s best to start with this little nugget:

I first heard this when I went to a hear Dr. Louisa Moats speak. She’s amazing! To read an interview with her, click here. The first time I heard this was from Dr. Louisa Moats, it totally woke me up! I had never really realized this or even thought about it! Now that I have been teaching reading for so long, it makes a lot of sense. Reading is an incredibly complex skill!

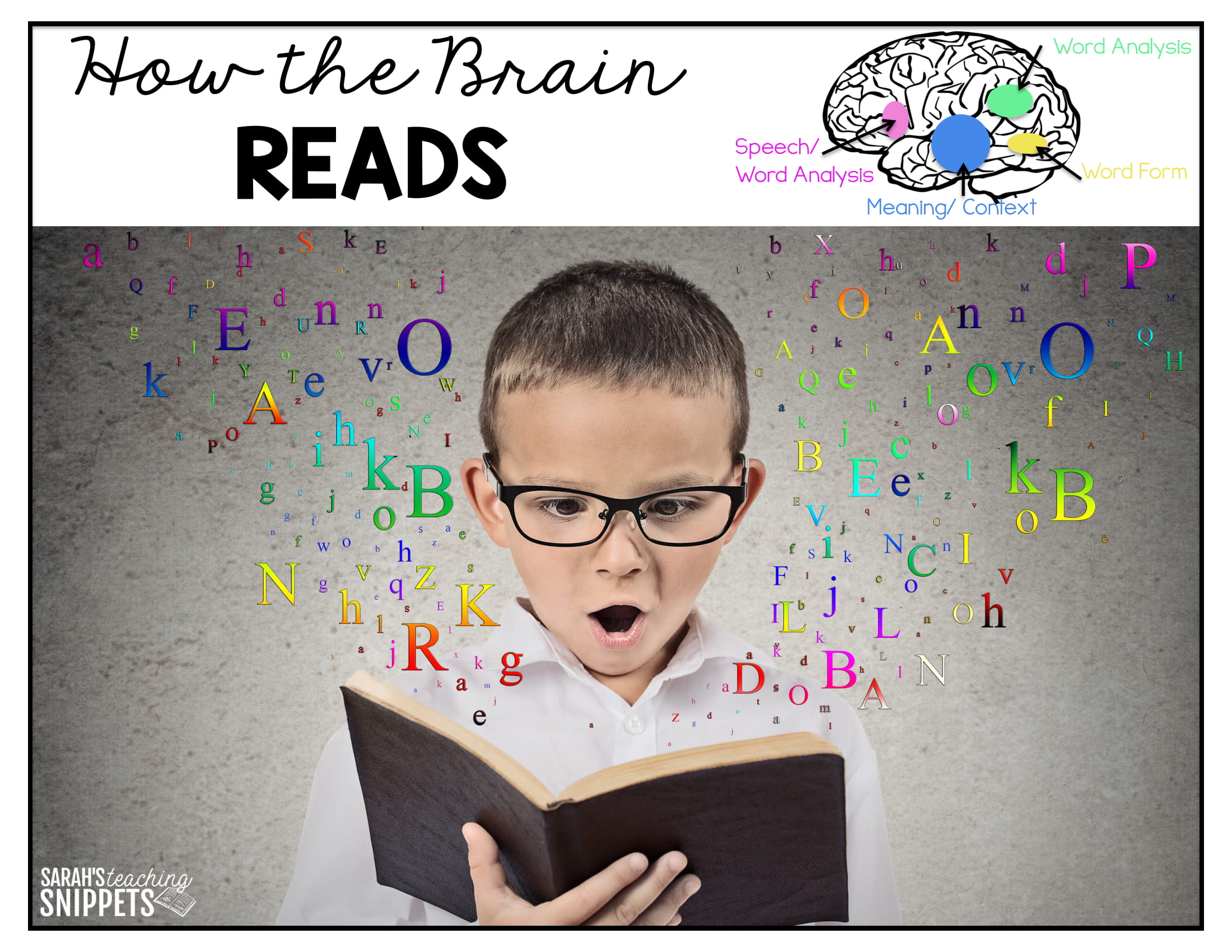

So if the brain is not “wired to read”, how do we do it?

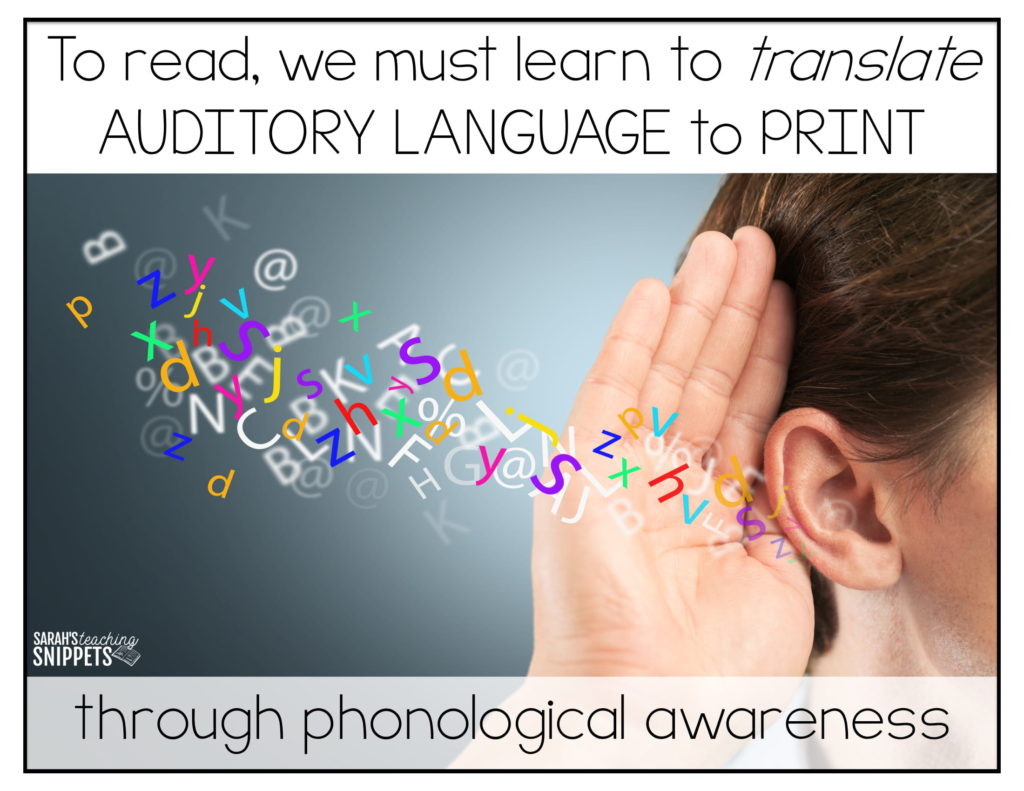

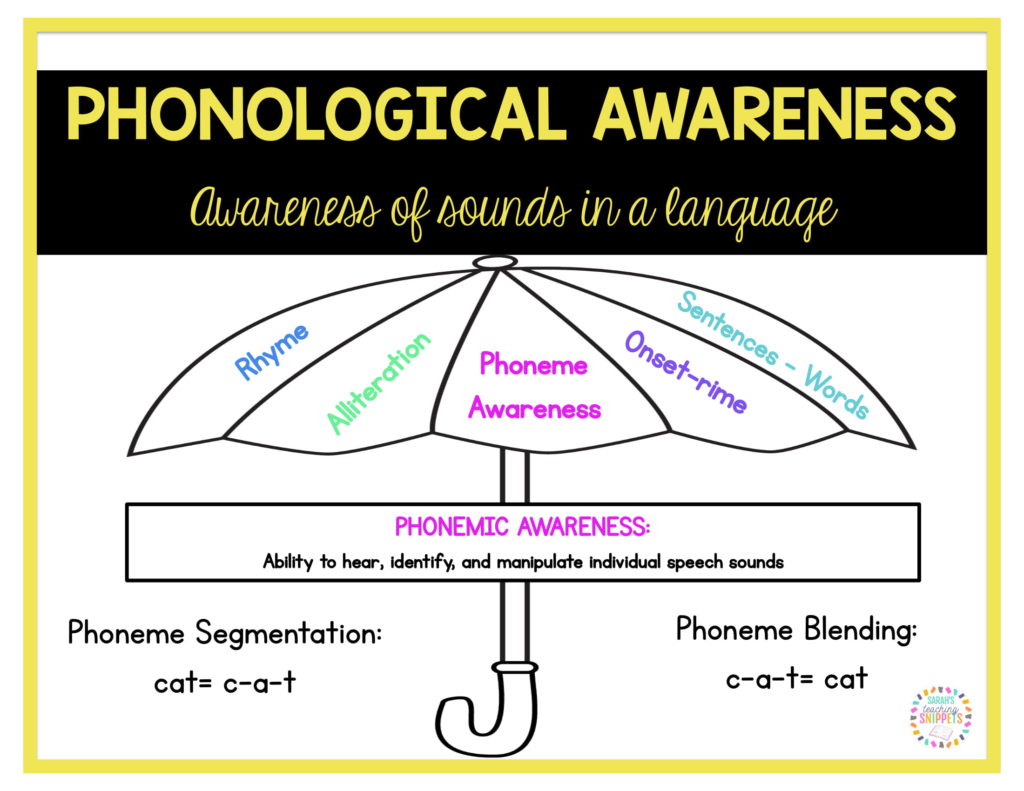

When we speak and listen, we don’t need to break apart the individual phonemes that make up words. In fact, we aren’t really aware of them at first. We say words as bigger parts.

When we learn to read and write, we must first figure out that all of our words are made up of smaller phonemes, or sounds. Instead of hearing and saying a word as a whole, we must break it apart into much smaller sounds.

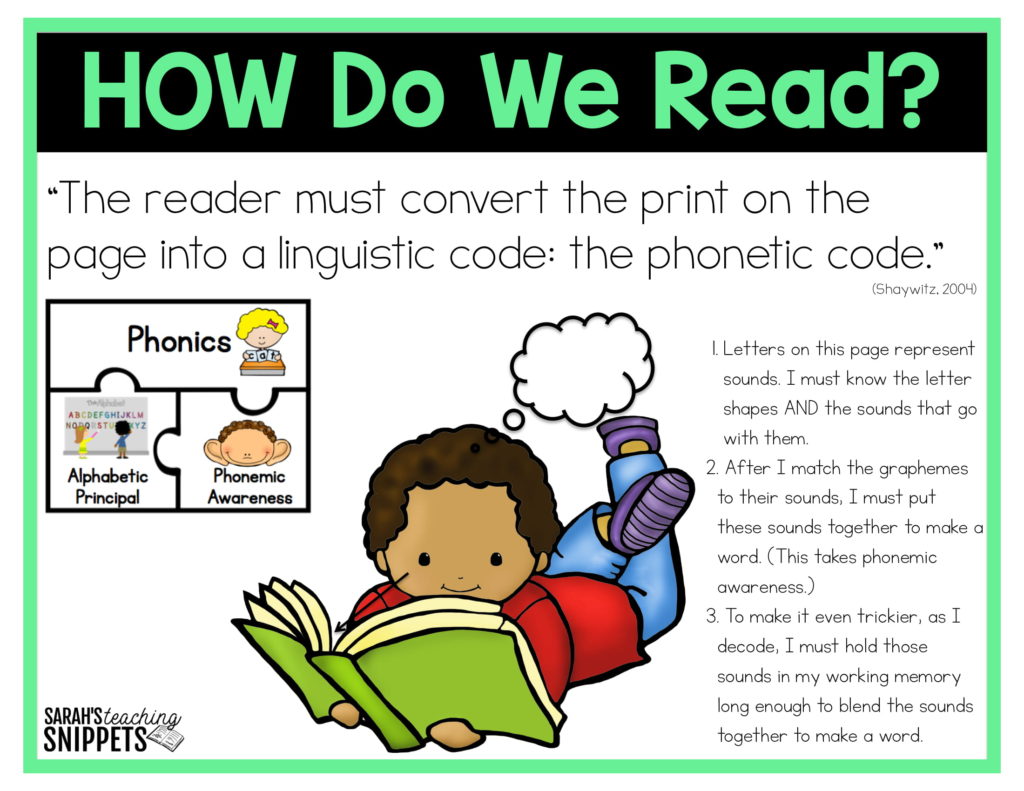

We rely on our language modules in our brains to convert this print into the linguistic code (phonetic code) we have created. We can’t do this until we have that ability to break apart words into their individual phonemes. “70-80% of American children learn how to transform printed symbols into a phonetic code without much difficulty.” (Shaywitz, 2003) Think about that. Are you thinking about the remaining 20-30%?

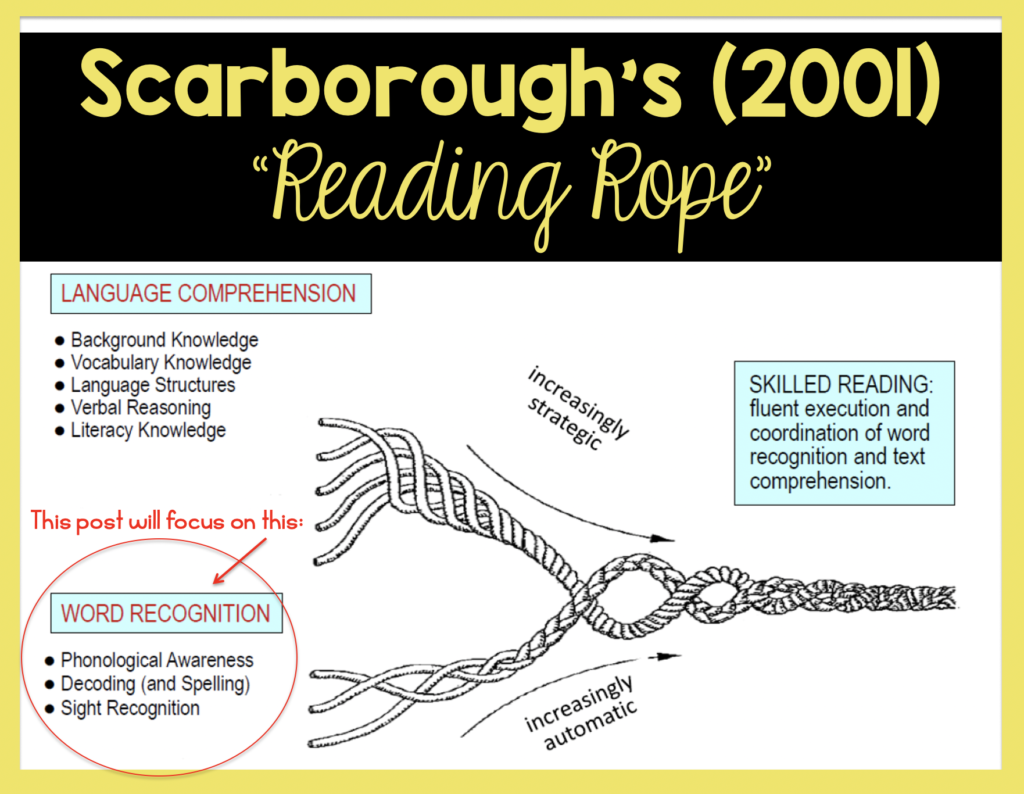

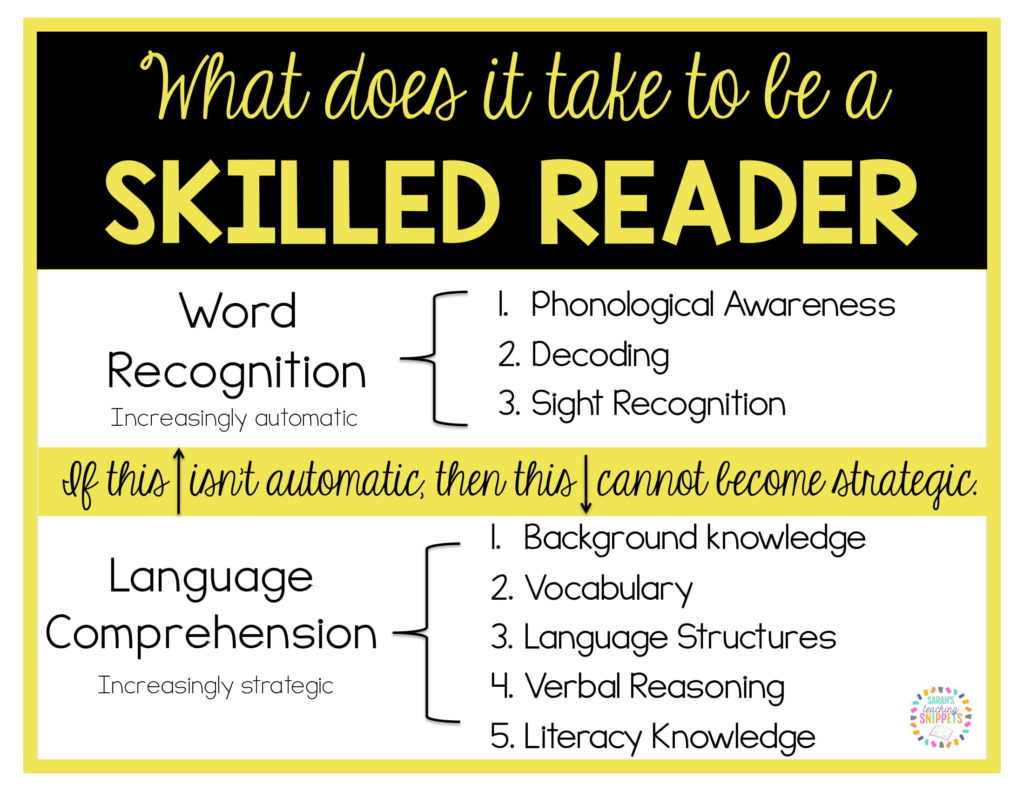

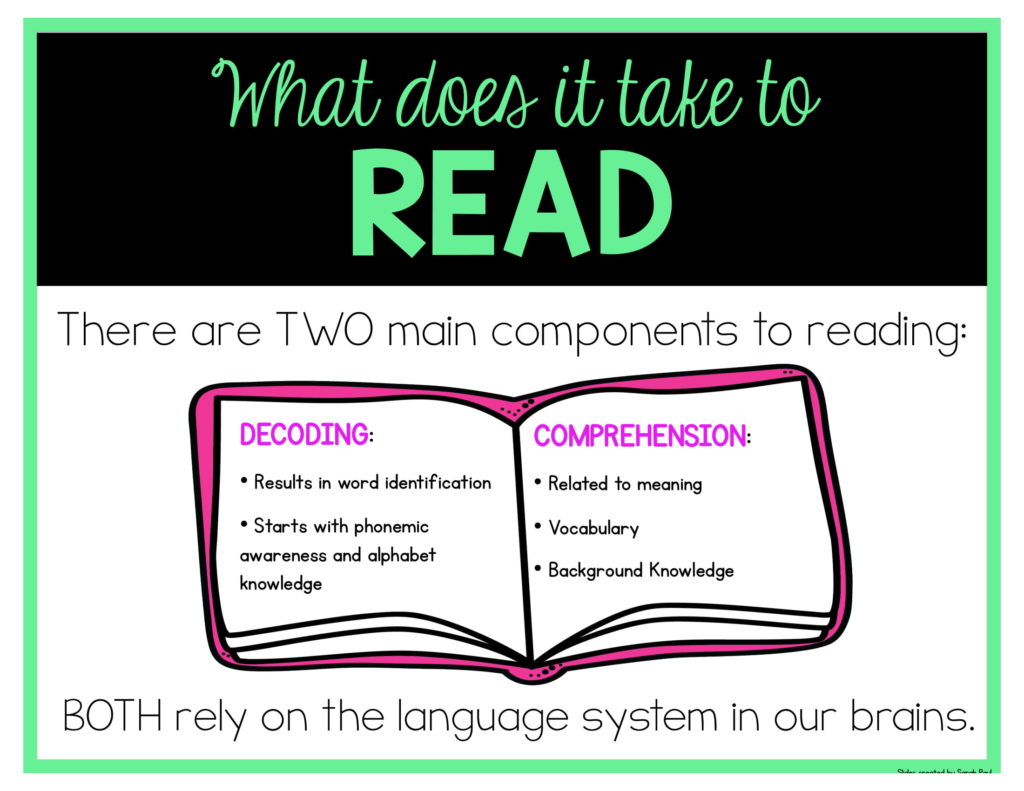

You may have seen this Scarborough rope before. Basically, it’s showing you what it takes to be a truly “skilled” readers. Many of our dyslexic students have the language comprehension, but the skills involved in the word recognition part is a roadblock. For this post, we will be focusing on that bottom part of this “rope.”

This is the same information, just another way to look at it:

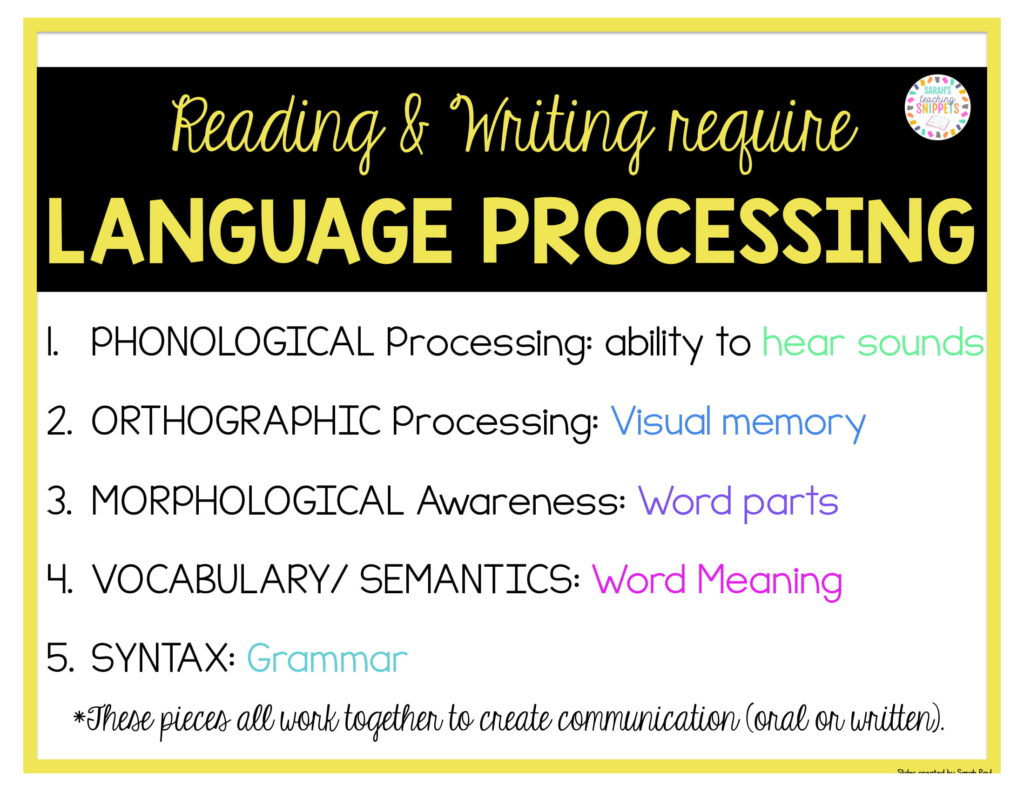

Since reading skills are tied to these language skills, it is important to look at all of them. I will come back to this slide later, when I talk more about reading instruction.

The Process of Learning To Read

Before we jump to the brain, let’s look a little more at the skills involved in the learning to read.

Students need to learn how to decode and then develop word recognition before they can read for meaning. However, you can still develop language comprehension from an early age that will later help them when they have the tools to read the actual words.

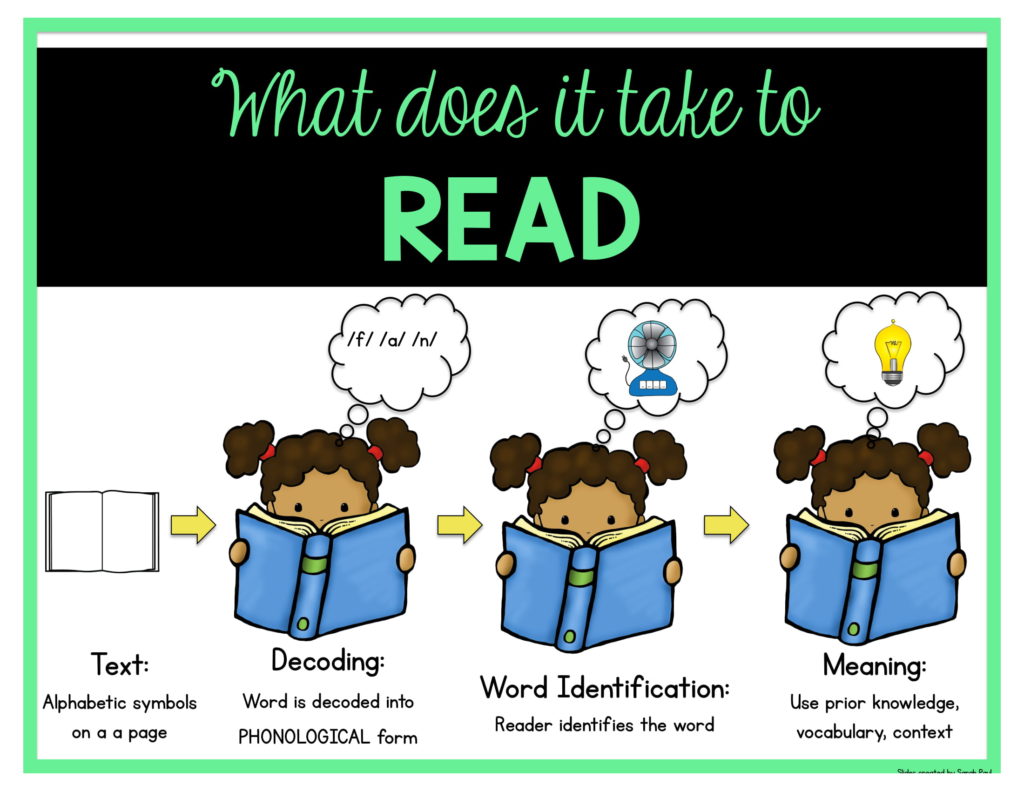

Breaking it down, here is how a child learns to read.

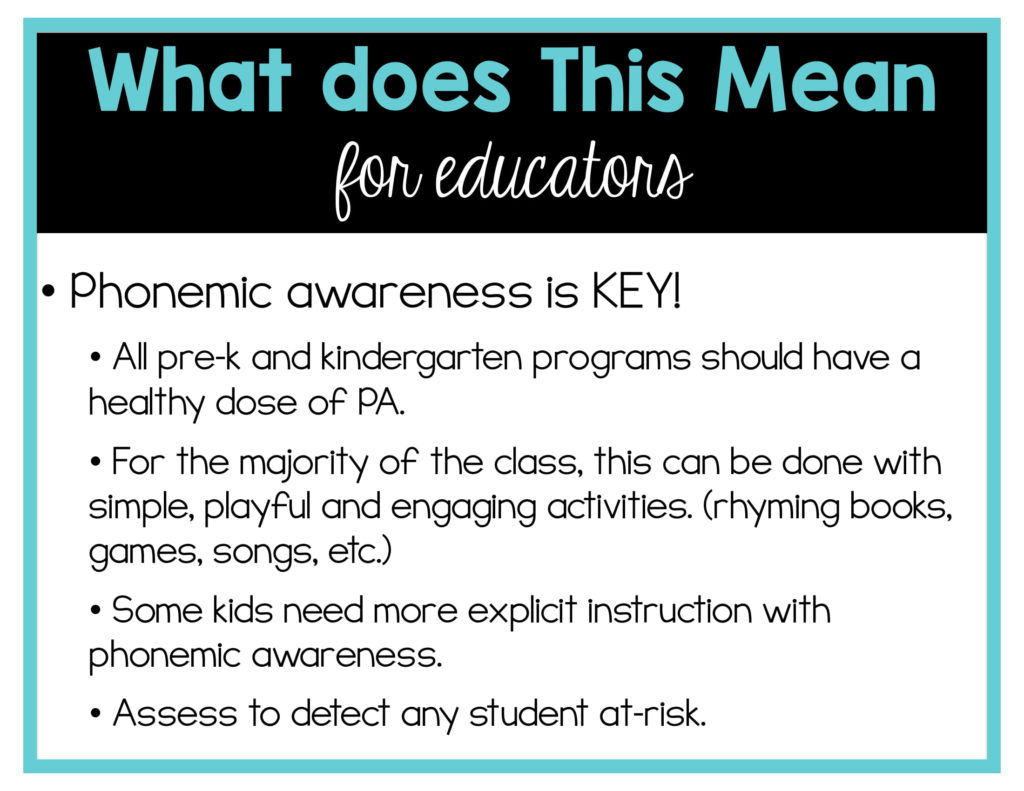

Phonological awareness comes easier to some kids than others. Many children develop it without any real instruction by the time they need to learn to read. Others need a little boost in the form of fun nursery rhymes, games that play with words, and minimal instruction. Still, there are many who need intensive instruction with phonemic awareness before beginning to learn to read.

To read more about phonological awareness, click HERE.

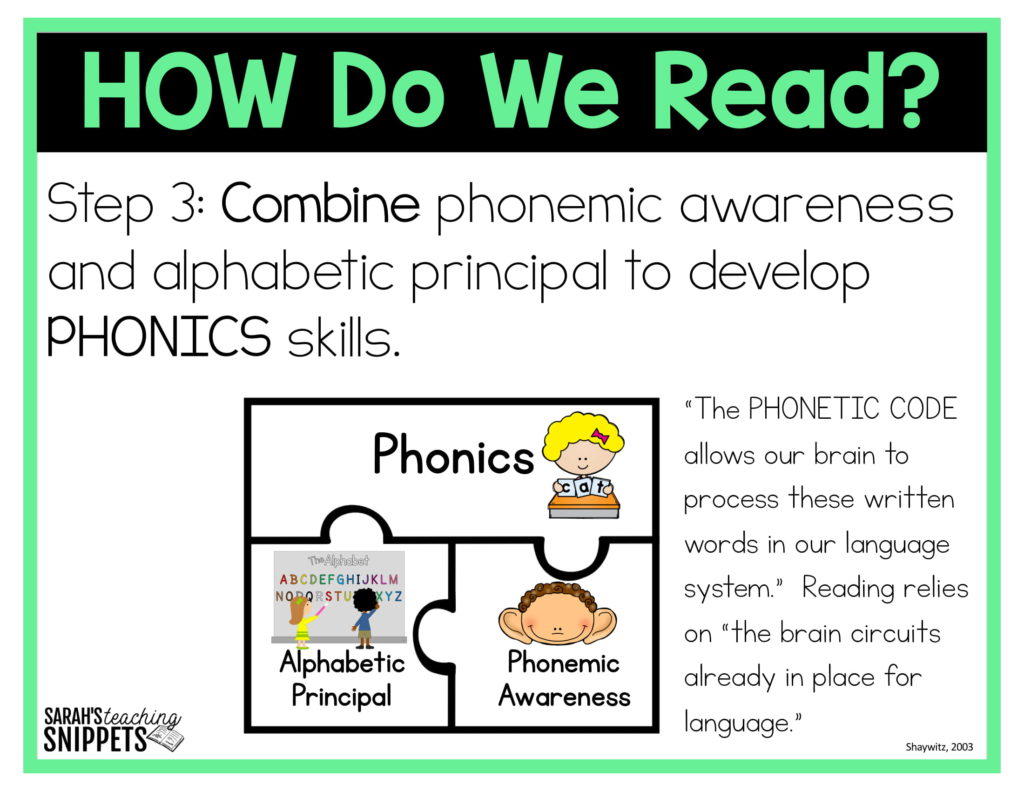

The alphabet principal is the idea that those lines and circles actually carry meaning when they are linked together. Words are made up of letters and letters represent sounds. To read about I teach the alphabet using a research-based approach, click here.

Applying decoding skills and developing word recognition is faster for some and slower for others. For many children, it can be incredible difficult. To read more about phonics, click here.

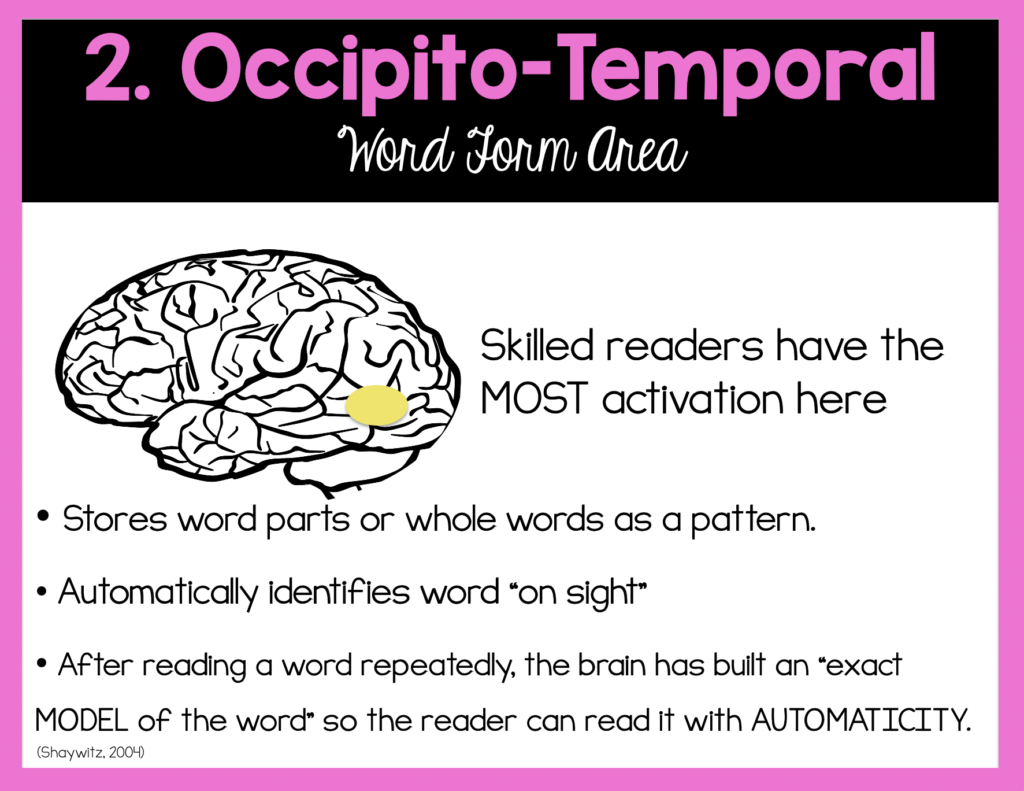

After students are able to decode words, they can start committing them to memory. To store a new word into long-term memory, the reader needs to link the sequence of letters to the pronunciation and meaning. The average reader needs to see a word 4-14 times before they can read it with automaticity. (Dyslexic readers need to see it 40+ times!) The more a reader is exposed to words, the quicker they are committing these words to memory. To read more about how we learn words, click here.

According to research, teaching students to sound out words actually “sparks more optimal brain circuitry than instructing them to memorize the word.” Isn’t that interesting?! (You can read more from this article HERE.) You will see below where in the brain this all happens.

I won’t be getting into comprehension in this post very much (because this is already too long), but obviously that is the end goal. It’s the whole reason why we teach phonics. Phonemic awareness and alphabetic principal leads to breaking the phonetic code which leads to automatic word retrieval which leads to fluency which allows the reader to truly gain access to the text and, hopefully, read for meaning.

Of course there are those students who can word call like crazy but can’t comprehend. That’s because that skill happens as a result of activation in a different part of the brain.

To read about how I teach comprehension, click here.

What is Happening in the Brain While we Read?

Now, onto what is happening in our brains when we are reading. Above is the process that we can see. As teachers, we see this happening every year with our students. They start out sounding out words, and as they year goes on, they become more and more fluent. By the end of first grade, most kids are reading 40-80 words/minute.

So, how does this happen? Why do some kids still struggle after loads of practice and quality instruction? The answers are all there, thanks to fMRI’s (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging.) Scientists can now literally see what is happening in our brains when we read and what is happening in the brains of struggling readers. I’m going to try to break it down as best I can. Keep in mind, science was not my subject in school at all. I also have no background in brain anything. 😉

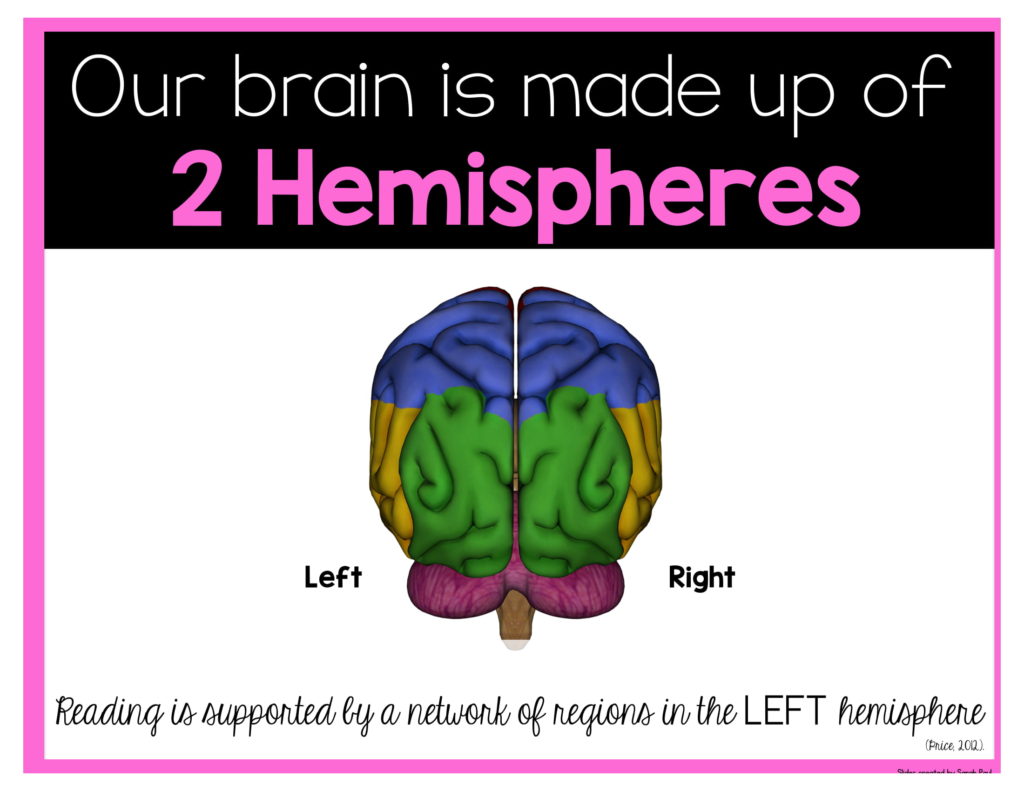

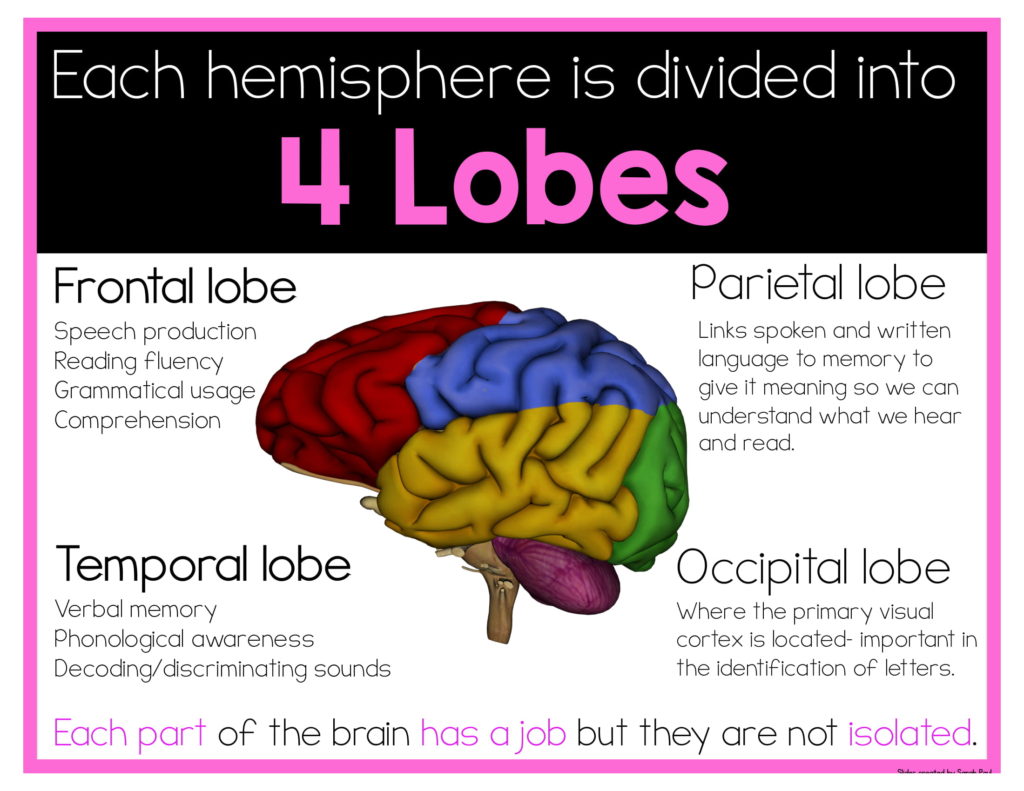

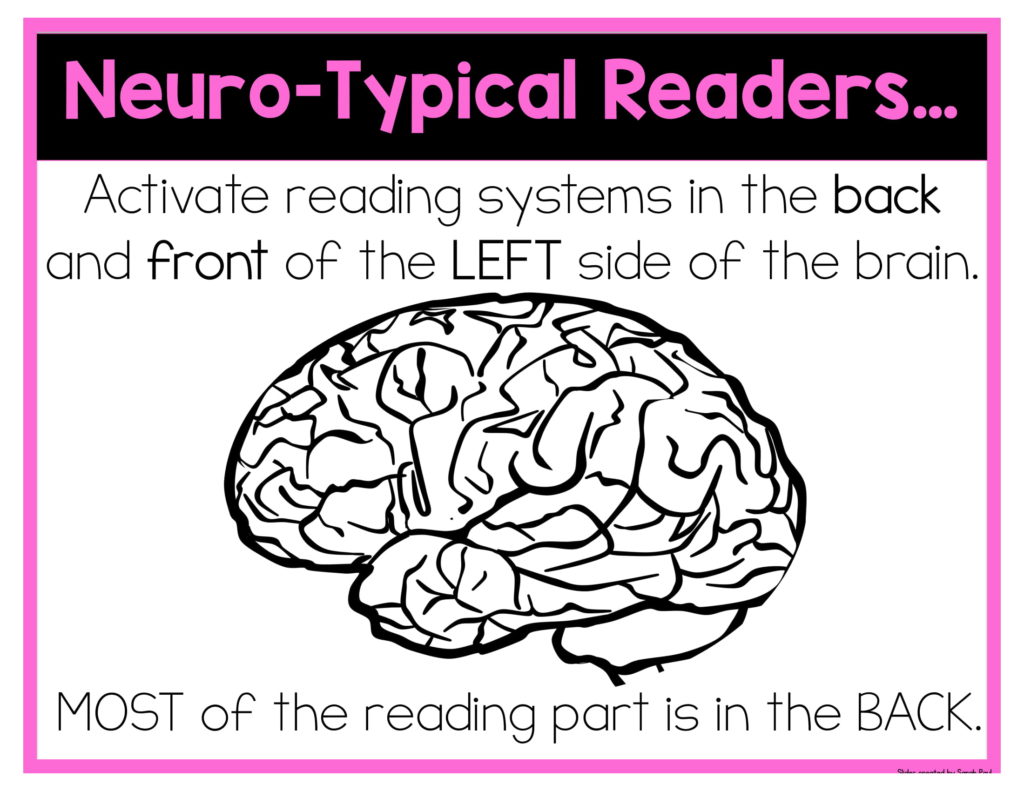

Reading is supported by a network of regions in the LEFT hemisphere.

Remember when I mentioned that reading is not a natural skill that we are born to do? There are no parts of the brain that are innately dedicated to learning to read. Instead there are parts of the brain that are used for spoken language and object recognition, which we use for reading. (Dehaene &Cohen, 2007)

Brain Systems Most Active While Reading

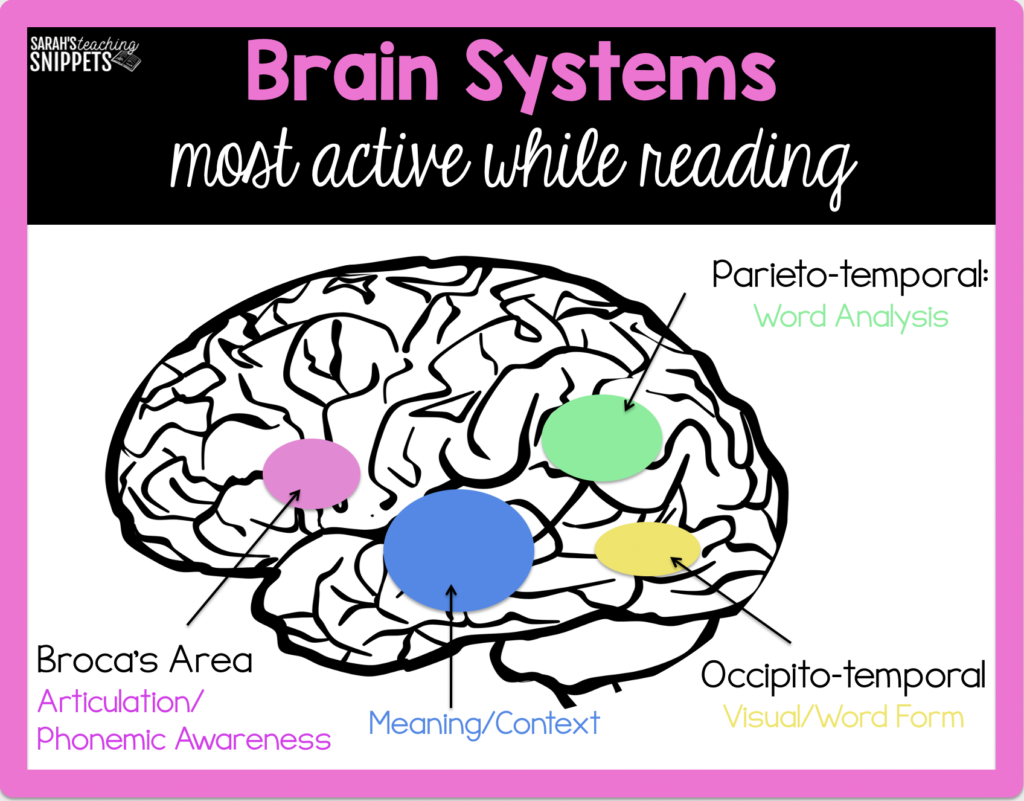

Through fMRI’s, scientists have found that there are four main brain systems that are active while reading.

Two of these pathways for reading are in the posterior system (back of the brain):

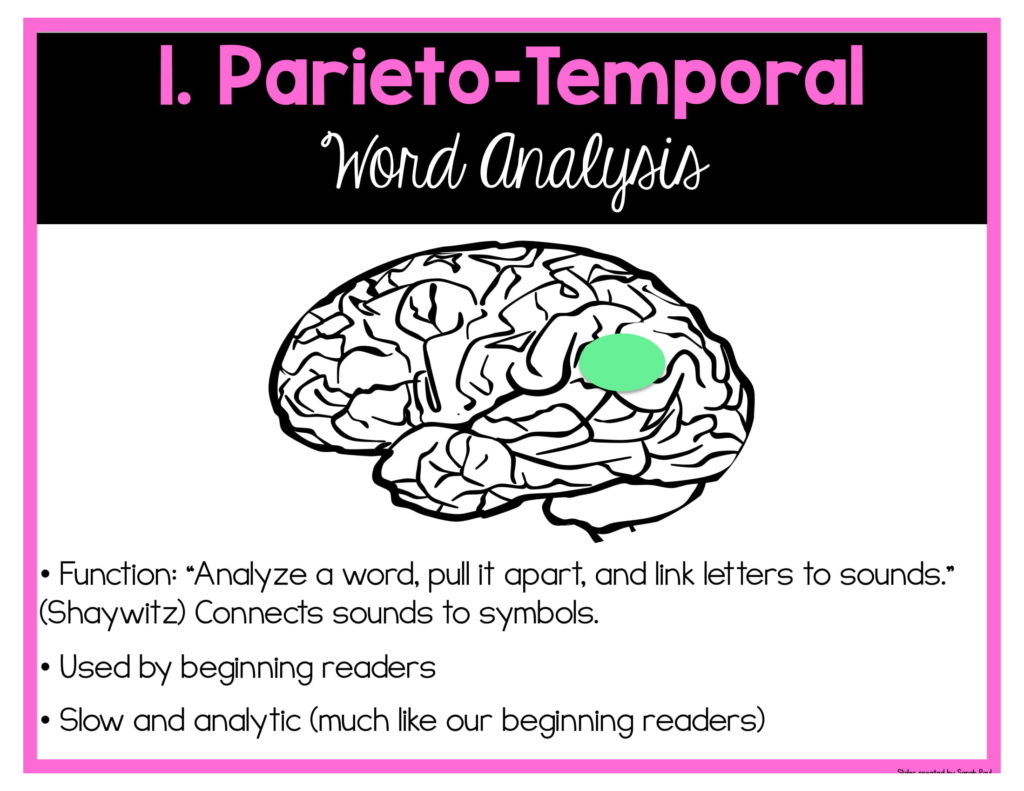

Think about our beginning readers. They are relying on this because they have not had enough exposure to automatically identify every word. (You’ll learn more about this in a sec.) Our new readers need multiple opportunities to practice this skill.

- They need to know the letters and the sounds they represent with automaticity. If they don’t have these sounds down, it will slow them down with this process. Simply knowing the letters and letter combinations isn’t enough. We need to give students plenty of practice to master this skill and develop automaticity.

- They need to have phonemic awareness (they must be able to pull those sounds apart and blend the individual sounds together with relative ease.)

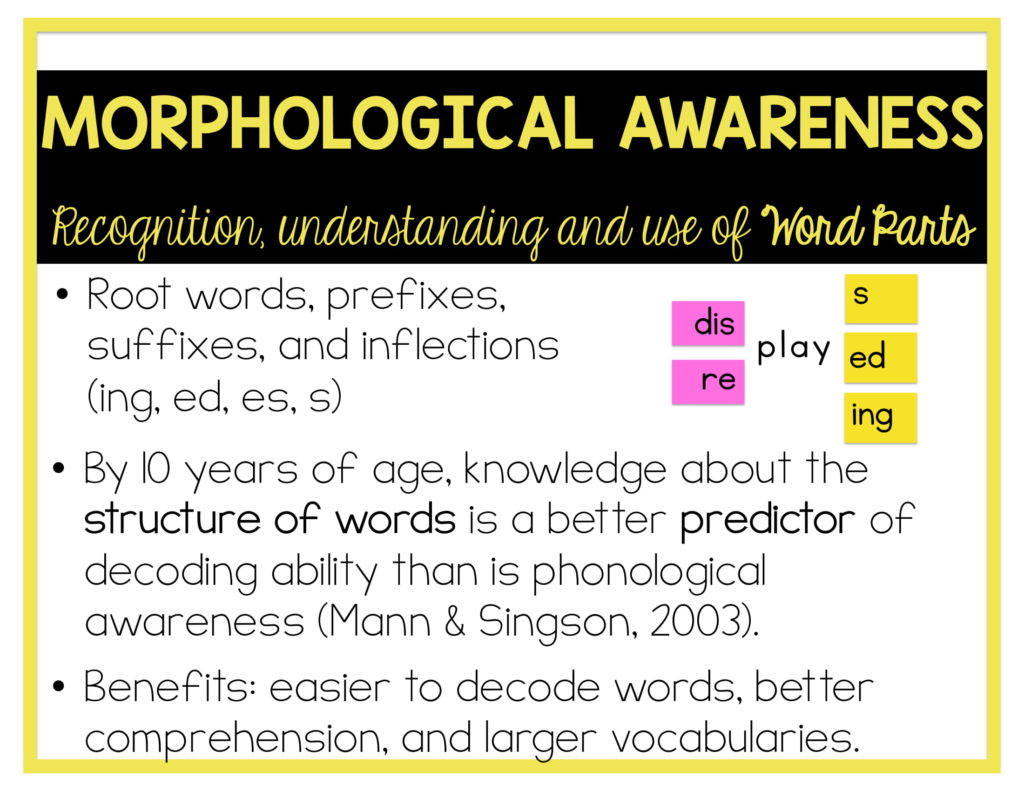

- Systematic, explicit phonics and morphology instruction helps students make the connections they need to turn print into meaning.

This is the part of the brain that we hope is getting busy as our students finish first grade and entering second grade, right?! This made a few things pop in my head when I read over this.

- It does start with phonics. Repetitive exposures to sounding out those words (reading and spelling) DOES usually lead to eventually recognizing the word with automaticity later.

- Phonics is a tool that gets us to that goal of automaticity.

- Back to that research I mentioned above. They found in the study that when teaching two groups using different methods (teaching phonics vs. whole word memorizing,) that the brain showed more activation on the left with the phonics method and more on the right with the whole word method. Strong activation on the left was the “hallmark” for skilled readers, which also happens to be lacking in struggling readers.

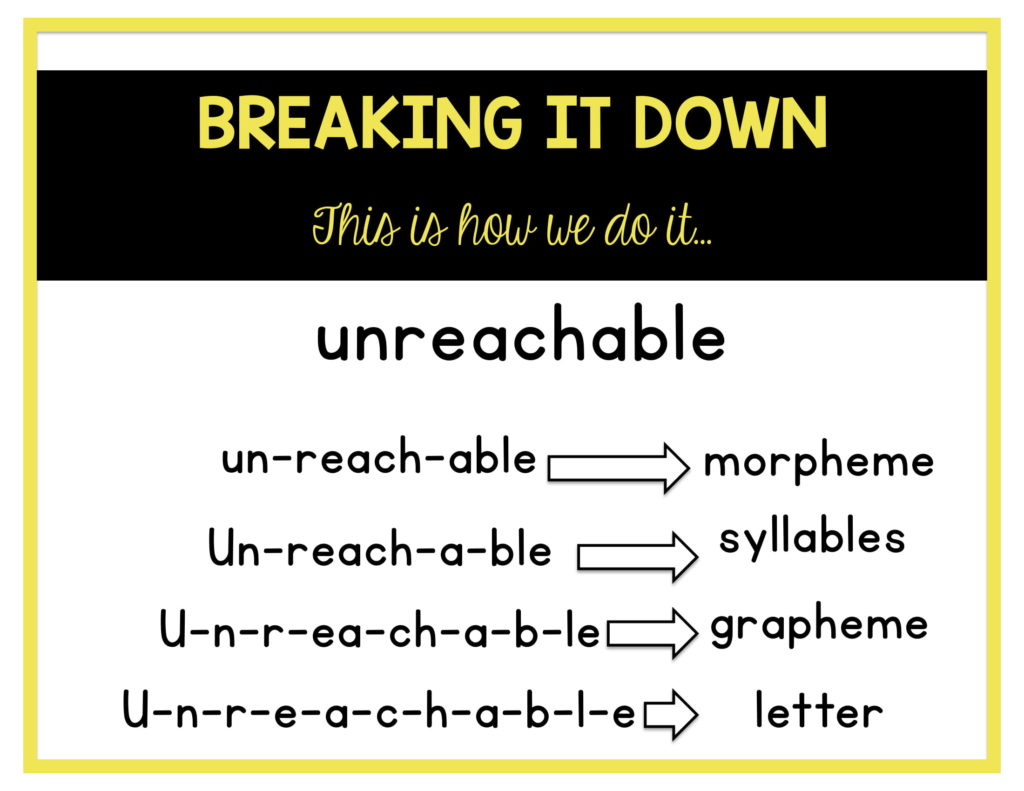

- I recently went to an excellent teacher training by PDX Reading Specialist, Barbara Steinberg. She pointed out that our brains can only hold so many words to be memorized. So what we are actually doing is memorizing word parts more often. These parts are what we retrieve so quickly and link together to make more words. This points more to the importance of teaching phonics and morphology.

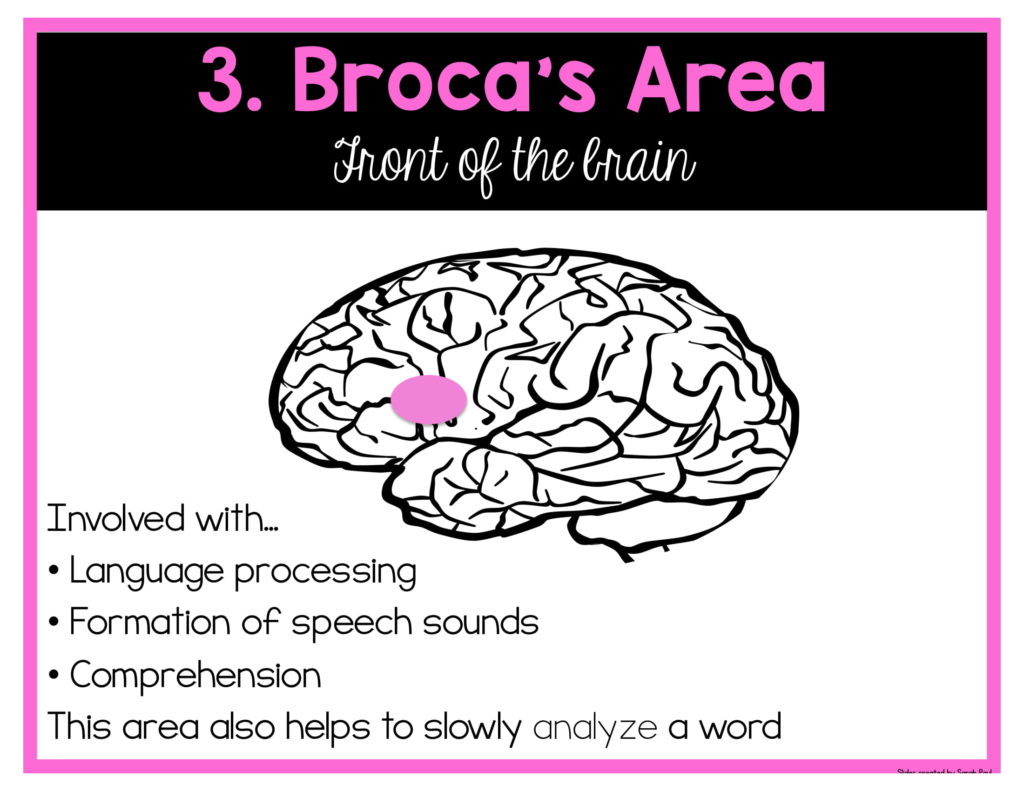

The third pathway is in the front of the brain in the Broca’s area. The frontal system is responsible for phonological processing and semantic processing (word analysis). (Willis, 2008)

The Broca’s area helps a person vocalize words and start to analyzing phonemes.

Neuro-typical readers rely on the left side of the brain for reading. Students with dyslexia rely more on the right side of the brain, resulting in reading that is slower and more labored.

With dyslexia, there is a neurobiological reason for why students struggle with reading. My next blog post is all about how a dyslexic brain reads. Here’s a hint- there are different levels of activation in various parts of the brain that I’ve mentioned.

The Language Processes of Skilled Readers

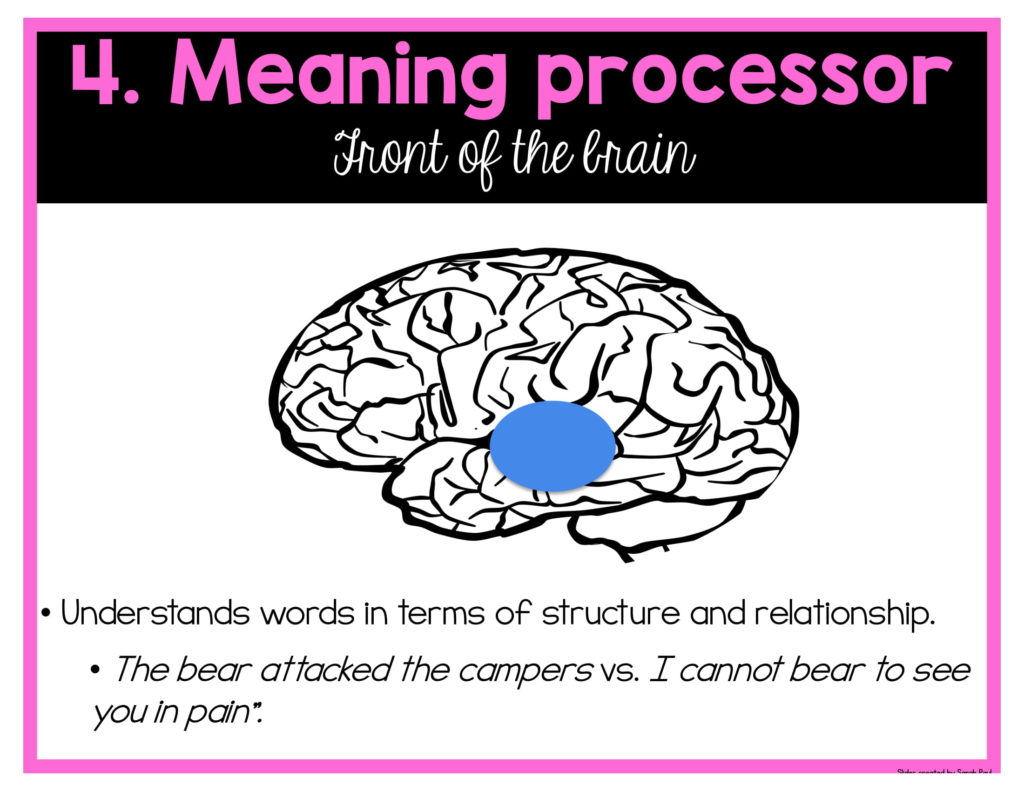

This brings us back to the yellow slides. When these brain systems all work together, it seems like reading is seamless. Let’s review the types of language processing that need to occur to be a skilled reader.

These are the major components of the structure of our language:

These pieces all work together to create meaningful communication (whether it be oral or written).

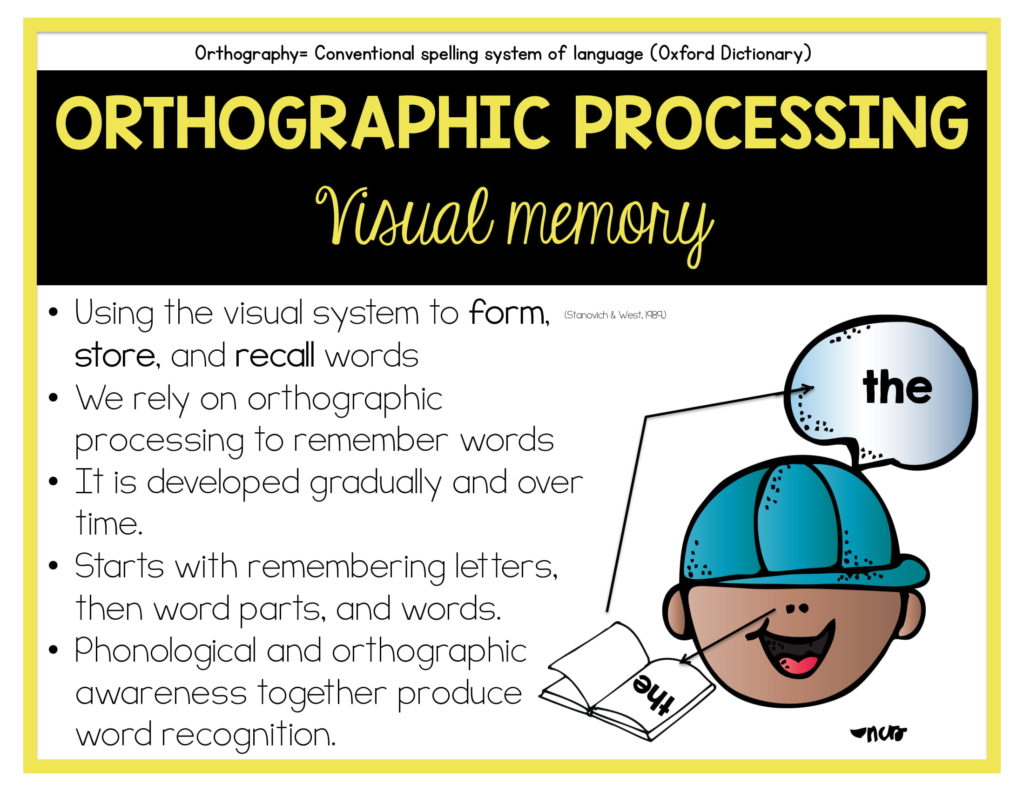

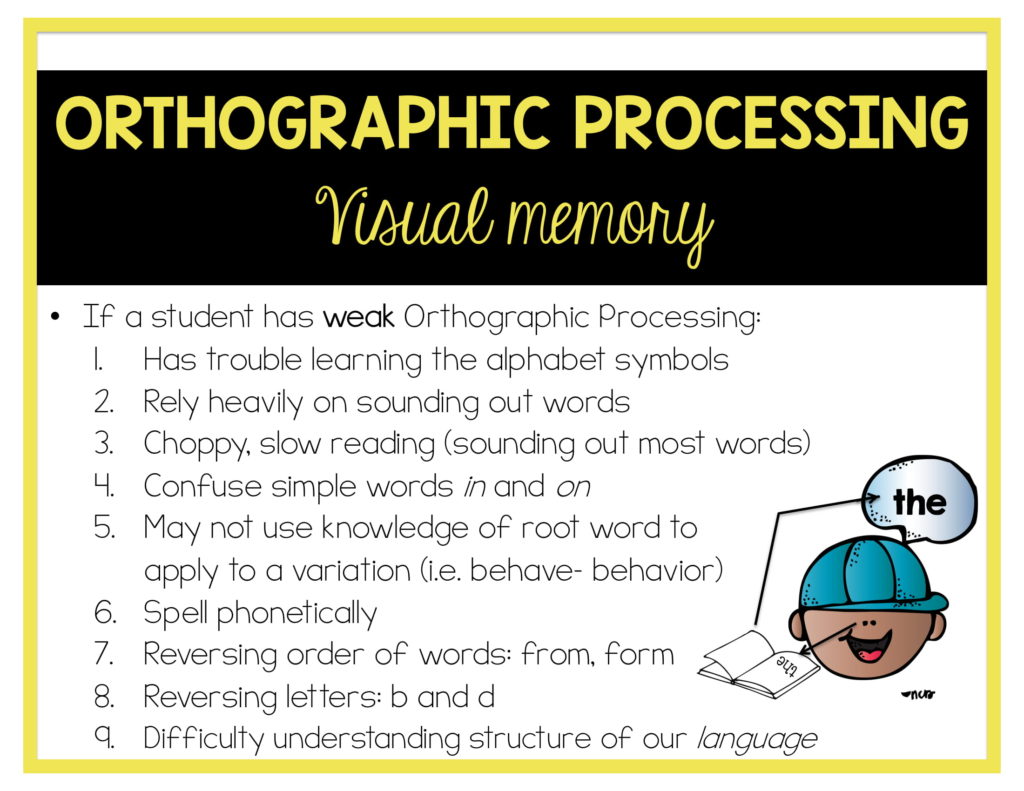

We all know how important this is! I’ve had students who seem to have great phonemic awareness but they cannot remember a word! They sound out words every time.

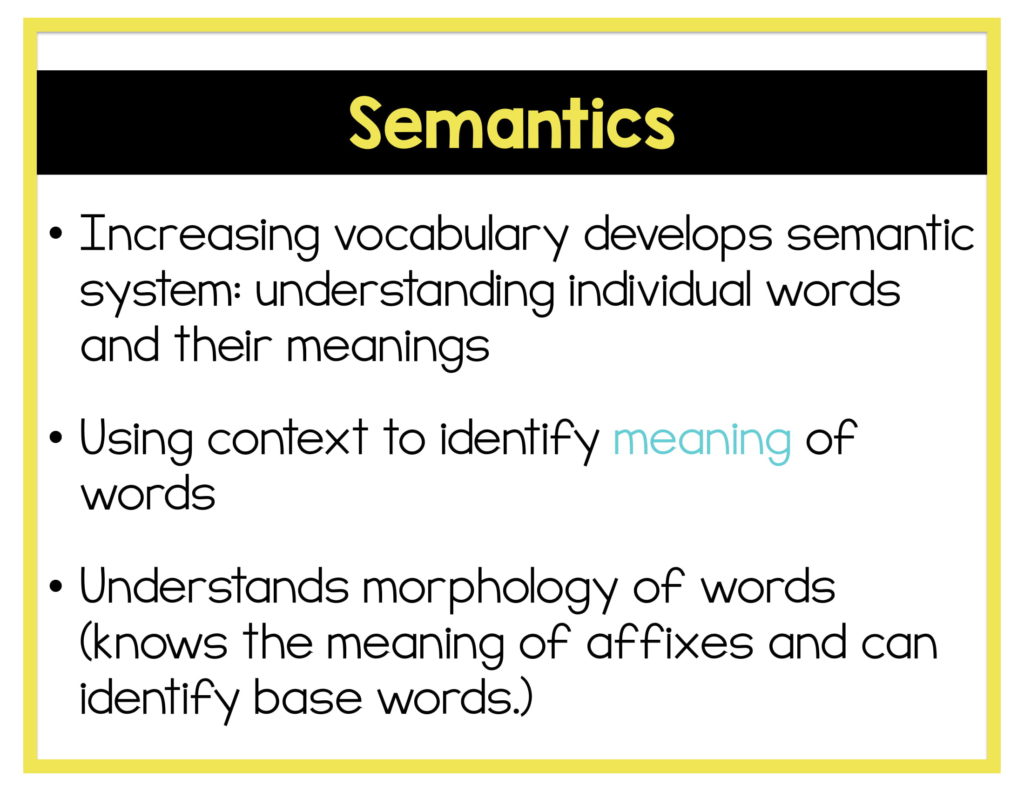

This slide above is to help with all the vocab I’m throwing at you…

These next slides show the higher level language skills. It’s important to start focusing on these even with our beginning readers. The frontal lobe is responsible for comprehension. Have you ever had a student that is a slow reader and bad speller BUT has awesome comprehension. Here’s why: The frontal systems are working like crazy. They are bright kids and they get it. Their brains are just not using the same pathways that would make their reading fluent. This is why we want to make sure that, although our remedial instruction is at their reading level, they are still exposed to TONS of literature at their intellectual level. Read-alouds and audio books are great for this. Have you ever had a struggling reader who is the first one to raise his/her hand with a thoughtful comment or question about your read-aloud? Yep. They need that and we need to make sure we are engaging their brains and helping them grow their vocabulary and higher-order thinking skills. (I promise- more about this in future posts!)

What Does This Mean for Educators?

Click here to read a post about an instructional approach called Structured Literacy.

Other Blog Posts about Dyslexia

Acknowledgements

I highly recommend reading Sally Shaywitz’s book called Overcoming Dyslexia.