This morphology post has been a long time coming! I have started and stopped so many times because it feels so big! I have had an interest in morphology for years and have slowly been developing my understanding of morphology and dabbling with how to incorporate morphology in the elementary classroom. I’ve always been hesitant to complete and publish this post because I still don’t have all the answers. But I decided a little snippet about morphology is better than nothing! Morphology is one of the components of a Structured Literacy classroom. To read more about Structured Literacy, click here.

I decided to split this blog post up into 3 blog posts. This first one will provide background knowledge about morphology. I’ve realized over the years that before I can truly help my students apply morphological concepts, I need to have a better understanding of morphology myself! I hope this first post can provide the background knowledge you need to get started. The second will be about teaching morphology in the primary grades (K-2) and then the third will be about teaching morphology the intermediate/upper grades.

What is Morphology?

Morphology is the branch of linguistics that deals with the structure and formation of words in a language. It focuses on the smallest units of meaning within words, known as morphemes. So, morphology is the study of how morphemes are combined to form words. I have found huge benefits to teaching morphology early and often. Usually in elementary classrooms, we focus on phonology, or the study of sounds in our language. This is absolutely essential! However, I have also found that sprinkling in morphology in the younger grades can set our students up for success by providing a deeper understanding of how words work. Then, by third grade we start to shift our focus from phonology to morphology. If they have some instruction all along, they are primed for more!

Morphological Awareness is the ability to consciously recognize, comprehend, and manipulate morphemes (Kirby & Bowers, 2012). The key word there is “consciously”. We manipulate morphemes all the time when we speak but we are not conscious of what we are doing or how we are doing it. My goal with younger students is to help them to become aware of this process.

What are Morphemes?

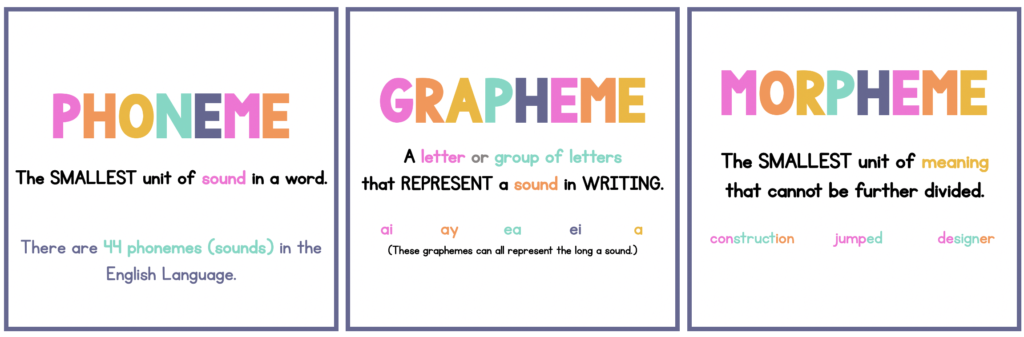

A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning. I always like to compare it to phonology, which is the study of sound patterns. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound. Letters and graphemes represent those sounds. By itself, a phoneme or grapheme does not carry any meaning. It is just a sound or a written representation of that sound. On the other hand, a morpheme does carry meaning. In her book, Beneath the Surface of Words, Sue Hegland says that “morphemes contribute to the overall sense of a word.” She goes on to explain that “Morphemes cannot be further divided without losing the sense they contribute to words.”

A morpheme can be an affix (like a prefix or a suffix) or a base word. A morpheme can also be a function word like “to”, “the”, or “of”.

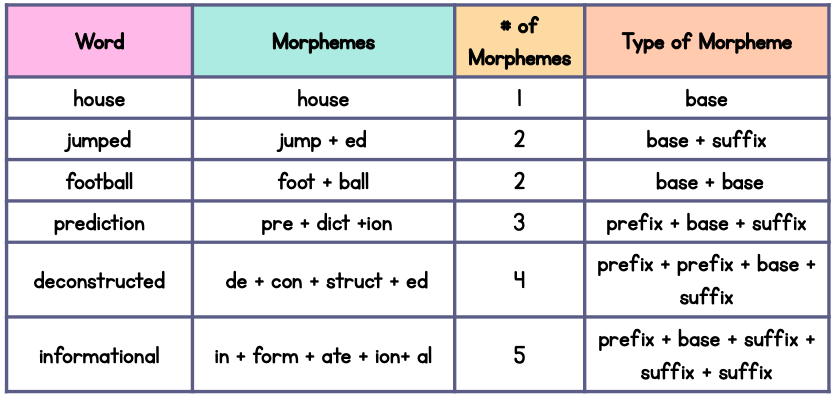

Examples of Morphemes

A word can have only one morpheme, or it can have several. I always think it’s easiest to understand with examples.

Types of Morphemes

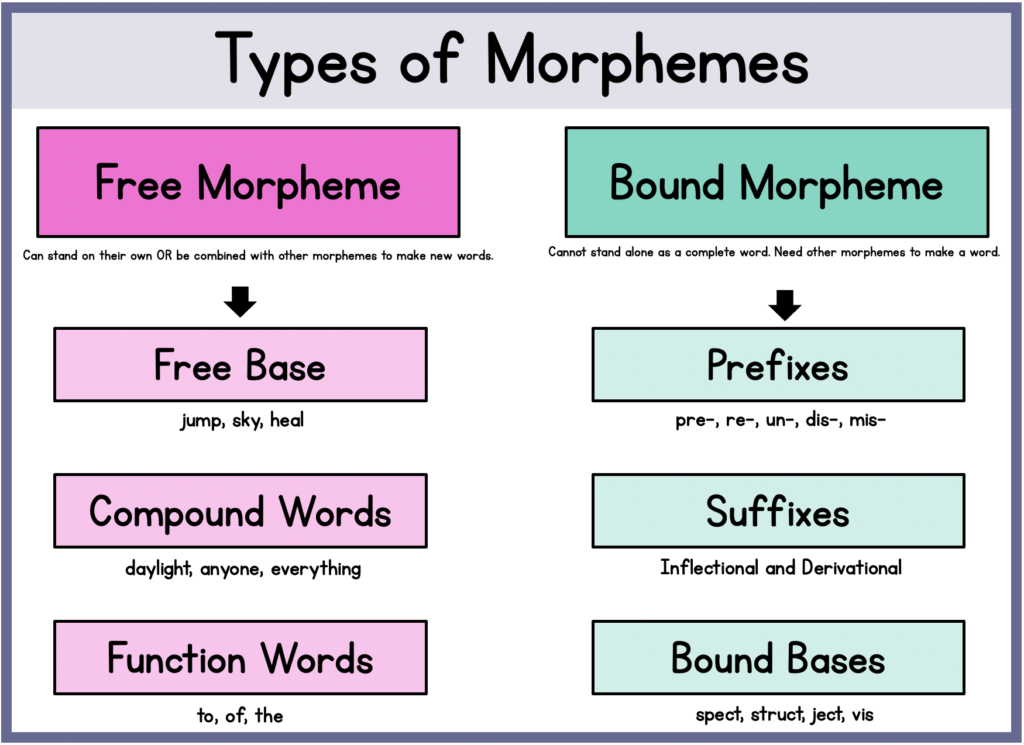

There are two types of morphemes: A free morpheme and a bound morpheme.

- A free morpheme can be a word all on its own, and it can also add additional morphemes to make new words.

- A bound morpheme cannot be a word on its own. It has to have other morphemes added to it in order for it to be a real word.

The image below shows the types of morphemes and examples of each:

Bases and Roots

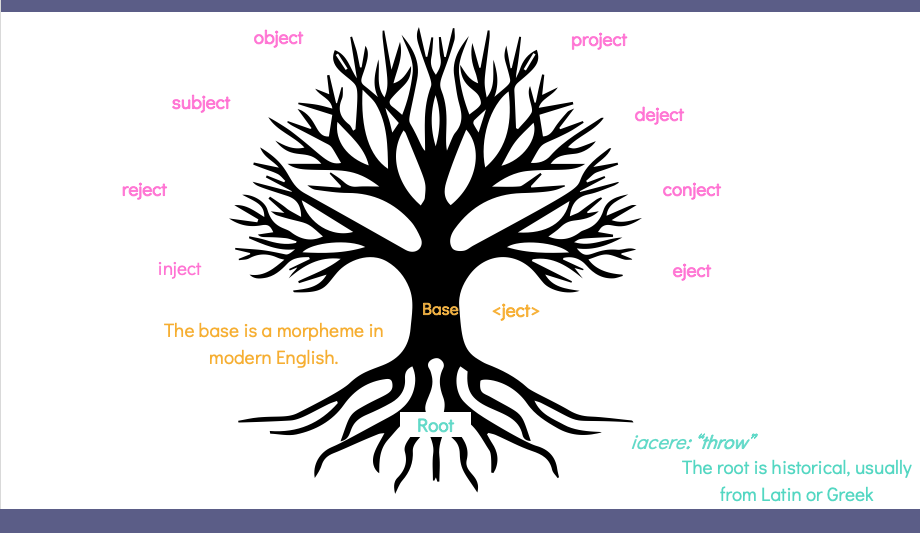

I get a lot of questions about the difference between base words and roots. I recently updated the image above to reflect my new understanding. Instead of using the word “root” I used the word “bound base”. I’ll explain why.

Base words hold the bulk of the word’s meaning. It is the core of the word. As Pete Bowers says, “Every word is a base or has a base.” A base can be free or bound. A free base can be a word on its own. It also can have additional morphemes attached to it to make new words. For example, “act” is a free base. It can be a word on its own, or you can add prefixes and suffixes to make “acted”, “react”, “action”, “reaction”, etc .

A bound base, on the other hand, does need other morphemes. That is what makes them a bound morpheme. Examples are “ject”, “struct”, “spect”, and “rupt”. You can add prefixes or suffixes to make these bound bases into words (instruct, construct, structure, inject, dejected, etc.)

It is easiest to start with free bases like “jump”, “rain”, and “play” and show how you attach affixes (prefixes and suffixes) to them to make other words.

So then, what is a root? I used to call “bound bases” “roots”. (In my resources, I still refer to them as such because that is the most common term for searching purposes.) However, I heard along the way that roots are technically the etymological source of a base, tracing back to its origins in older languages like Latin or Greek. Think of roots as the historical “seed”. From that seed, many English words have grown! For example, the base of “erupt” is <rupt>, but the root is “rumpere” from Latin. (For the record, I think it’s fine to call a bound base a root, but I wanted to share that new learning because I think it’s interesting and it makes a lot of sense!)

For resources to help you teach this, click here.

Affixes: Prefixes and Suffixes

As I mentioned, the base carries the bulk of the word’s meaning. We tend to teach free base words in the primary grades (k-2) and then get into bound bases later (starting in 2nd, but mainly 3rd grade and beyond). Prefixes and suffixes are both affixes. They are bound morphemes because they are not words on their own, but they are added to the beginning or end of a base word or root to change that word.

Prefixes

Prefixes are affixes attached to the beginning of words. Prefixes modify the meaning of words. “Prefixes negate the meaning of a word, intensify the meaning, or change the direction.” (Unlocking the Logic of English by Denise Eide)

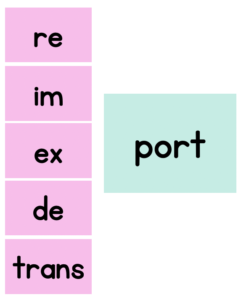

Take a look at the example below. All of these prefixes can be attached to the same base. <port> means “to carry”. Each prefix changes the meaning of the word. When you report, you carry back information. When you “import” something, you carry it in. When you “export”, you carry it out. Transporting is to carry across from one place to another and deport is to carry from a place. Pretty fun, right?!

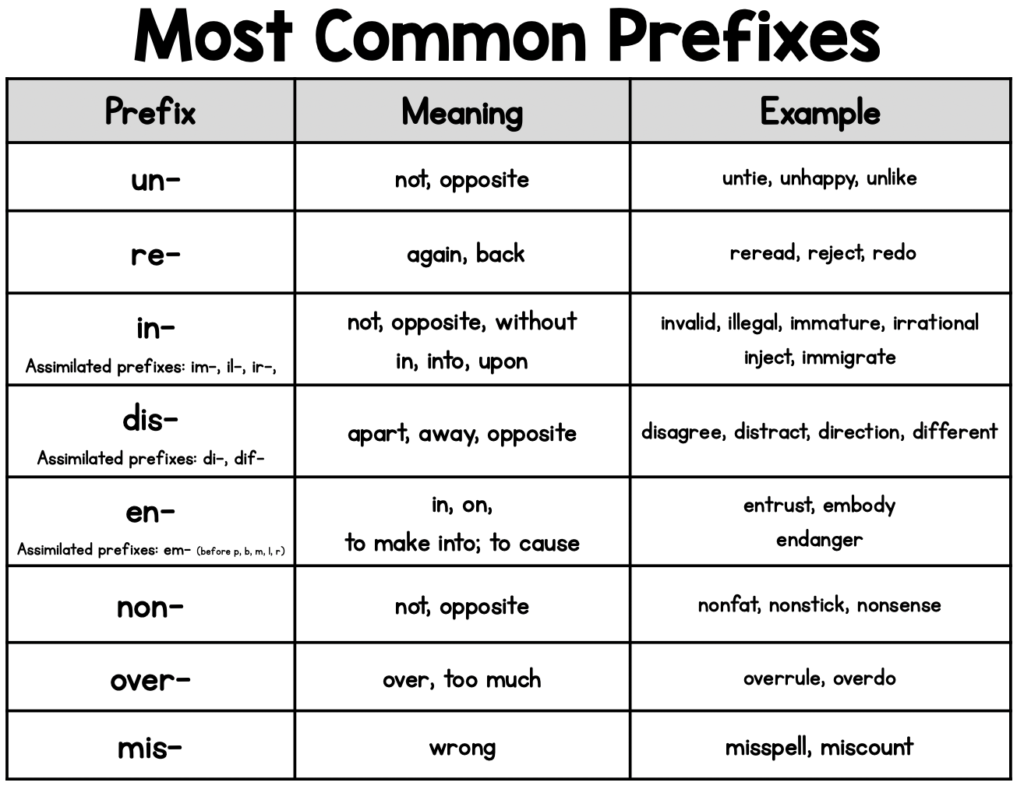

The 4 most common prefixes (dis-, in-, re-, un-) in English “account for 97% of prefixed words in printed school English”. (Scholastic source here)

These nine prefixes account for 75% of words that use a prefix.

I have created some prefix posters. I will also be making prefix units, but my to-do list is quite long!

Suffixes

Suffixes are affixes attached to the end of words.

The 4 most common suffixes (-s/-es, -ed, -ing, -ly) “account for 95% of suffixed words in printed school English.” (Scholastic source here)

Ten suffixes (-s/-es, -ed, -ing, -ly, -er/or, -ion, -ible/able, -al/ial, -y, -ness) account for 85% of words that contain a suffix.

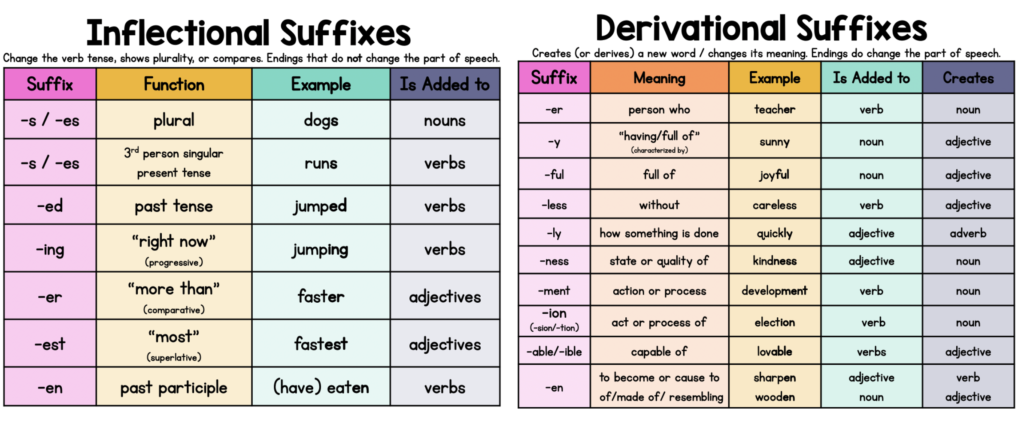

There are two types of suffixes: inflectional and derivational. (I do not get into these terms with my younger students. I simply use the term suffix. I am sharing this for your background knowledge.)

- Inflectional suffixes change the verb tense (-ed, -ing, -s, -es), pluralize nouns (-s, -es), or show comparison (-er, -est). These endings do not change the part of speech.

- Derivational suffixes create (or derive) a new word. It changes its meaning. These endings do change the part of speech.

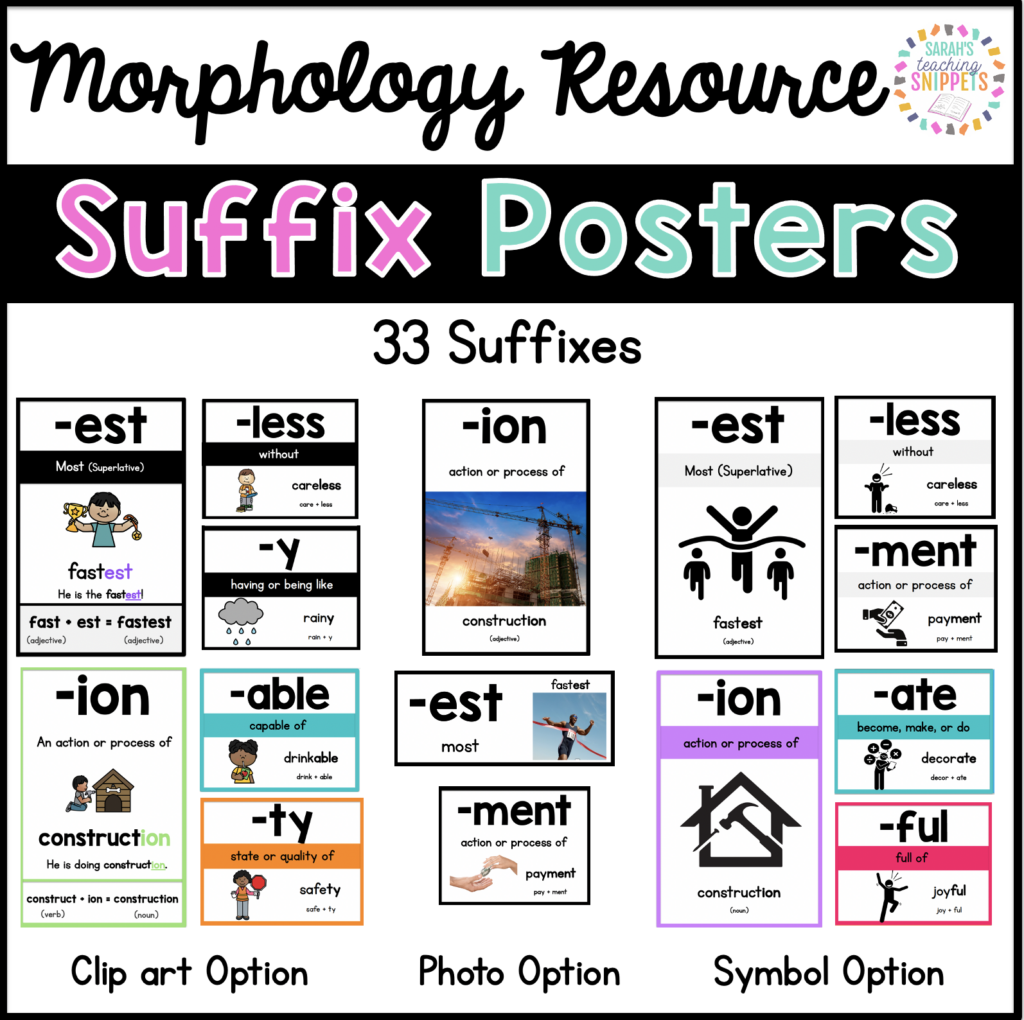

I have created suffix posters. There are three options: clip art, photo, or symbol. There are also several size options. You can find those suffix visuals here. I also have a bundle of suffix, prefix, and “root” posters. You can find that here.

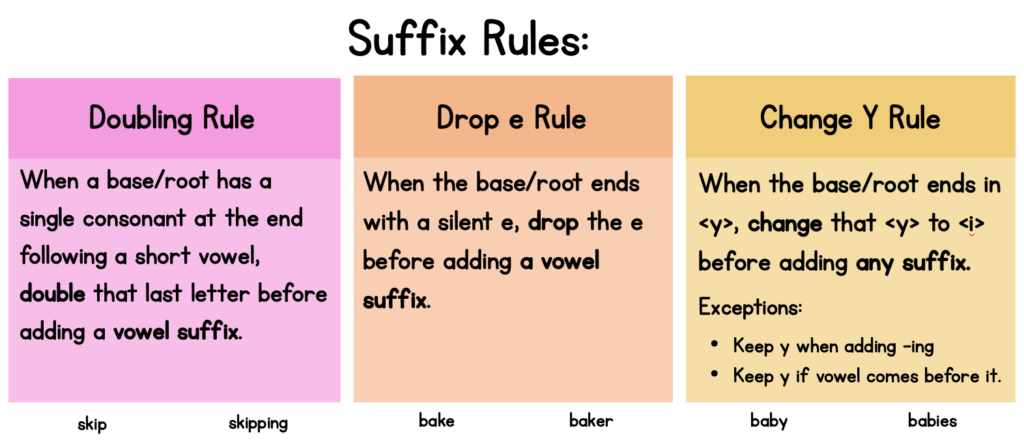

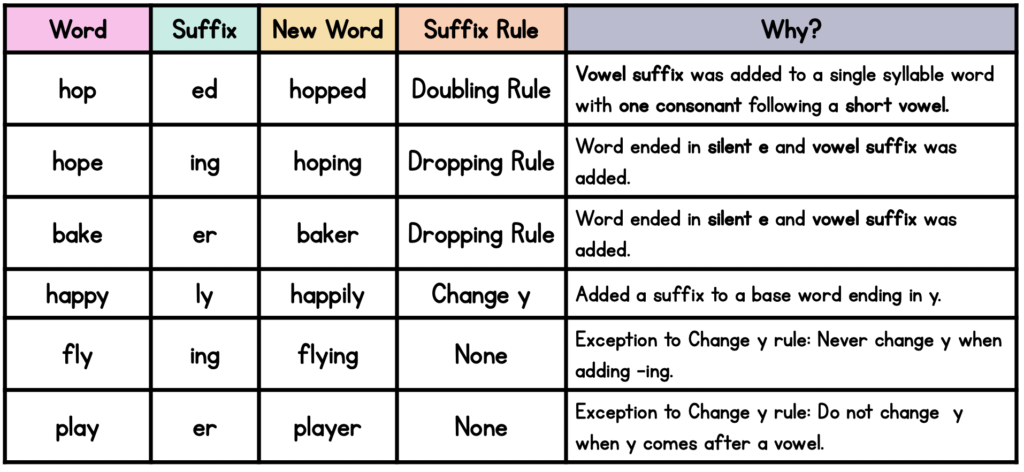

Suffix Changing Rules

Unlike with prefixes, adding suffixes isn’t always straightforward. When you add a prefix to a word you just add it. It doesn’t affect the base word at all. On the other hand, when adding, the base can change. But don’t worry! There are very consistent suffix-changing rules that you will see over and over again. The consistency of these rules makes them easier for kids to grasp and understand. The rule that applies to a suffix depends on what kind of suffix it is: a consonant suffix or a vowel suffix. (Consonant suffixes begin with a consonant. Vowel suffixes begin with a vowel.) Most of time, when we add a consonant suffix to a base, the spelling of the base remains the same (except the y changing rule). No letters of the base are changed or added. However, when you add a vowel suffix to a base, changes often may be made.

I first teach the doubling rule at the end of my closed syllable unit. I review it again and again though, because it takes a while to get! I teach the drop e rules with my silent e unit. I teach the change y rule with my open syllables unit. (More about that in the next post!)

Here are some examples of those words in action. I hope it helps!

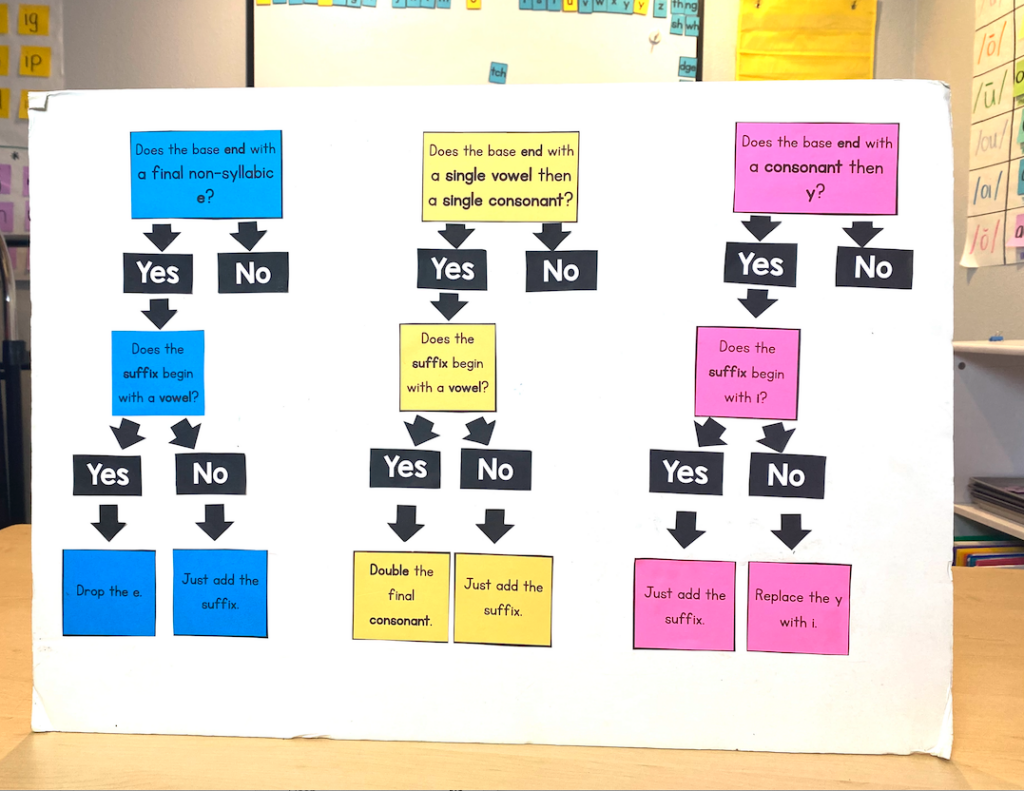

After I’ve taught all the suffix-changing rules, I use this poster when working with small groups on spelling. Begin at the top and ask those questions. Follow the flow chart to figure out if you need to change anything. This poster is part of my Suffix Rules resource.

This suffix rules resource has detailed lesson plans, student worksheets, posters, and a game! You can find it here.

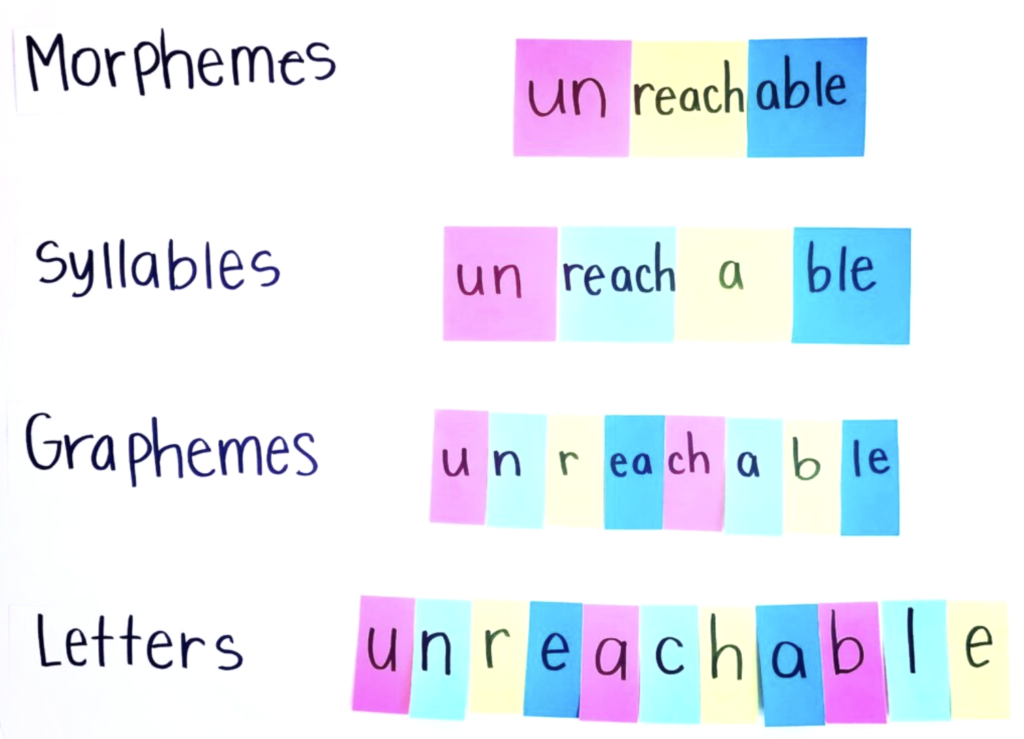

Morphemes Compared to Other Linguistic Terms

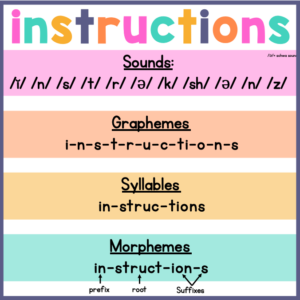

I posted this visual several years ago on Instagram and it seemed to help with understanding these terms.

There is often confusion about the difference between graphemes and letters. There are 26 letters of the alphabet. However, there are 44 sounds (phonemes) in our language. Graphemes are the written representation of those sounds. Graphemes can be one letter, or they can be more than one letter. For example, the sound (phoneme) /b/ is represented by the grapheme <b> (which is also a letter). The sound (phoneme) /sh/ is represented by the grapheme <sh>. (The letters <s> and <h> together form the grapheme that spells /sh/.)

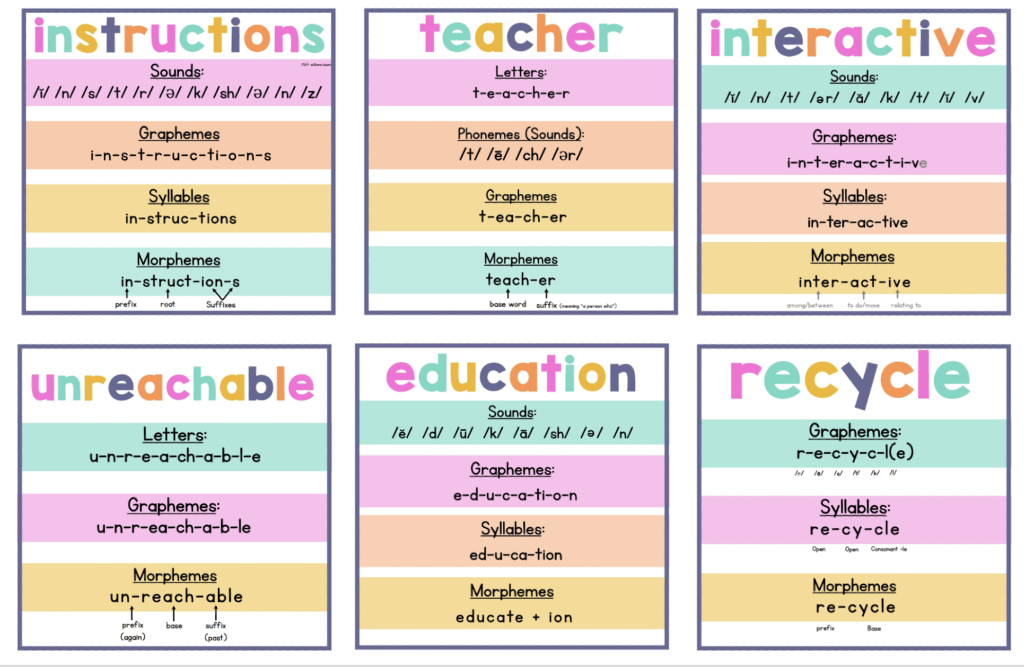

If you like those examples, I have created a few more and posted them on Instagram from time to time.

If you would like to download these examples, click here.

Morphemes vs. Syllables

Morphemes and syllables are easily confused. A syllable has to do with sound. It’s like a beat in a word. It is a chunk of sound that revolves around a vowel. With each syllable, our chin drops, creating a separation. You can hear and feel syllables. You cannot always hear each morpheme. A morpheme is a piece of a word that has meaning. In short, a syllable is like a beat in a word, and a morpheme is a meaningful piece of a word.

A great example of this is with the syllable -tion. The syllable -tion consistently spells the sound “shun”. However, did you know that the suffix is actually -ion?

Let’s look at the word “instruction.” When I break it up into syllables, I would say in-struc-tion. By contrast, when I break it up by morpheme, it is prefix in-, root “struct” (to build) and suffix -ion (in-struct-ion). The root is “struct” with that <t> being part of the root. The suffix is -ion. By itself, suffix -ion doesn’t say “shun”. It is only when it is combined with the <t> from the root that is says “shun”.

The same is true for syllable -ture vs. suffix -ure. In the word “fracture”, the syllables are frac-ture (with -ture saying “cher”), but the morphemes are root “fract” meaning to break and suffix -ure. This may seem confusing at first, but I’ve taught these same concepts to second and third graders and after much exposure and investigating lots of words, it clicks and makes sense to them. (More to come on that in the third blog post of this series.)

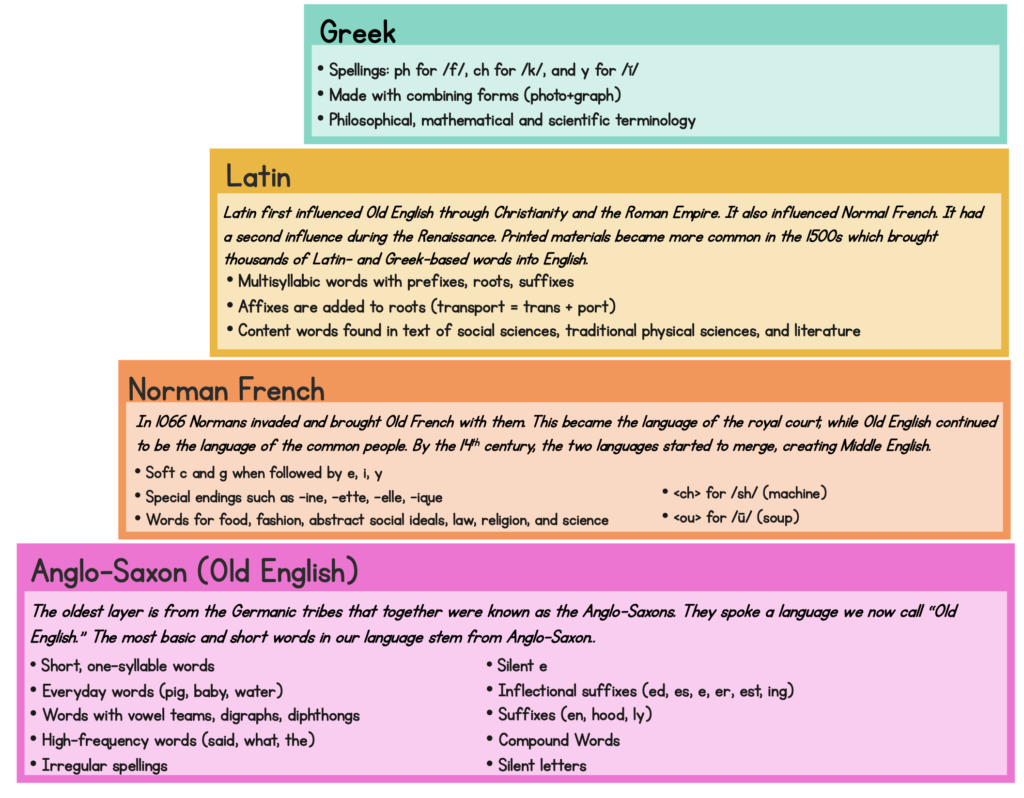

Influences on the English Language

One of the reasons why our language is so complicated (and interesting) is because it has many influences from other languages. The English language reflects English history. I don’t get into this with my younger students, but it could be interesting for older students. Here is a quick breakdown. (Information is from Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling LETRS: Module 4)

Why Should I Teach Morphology?

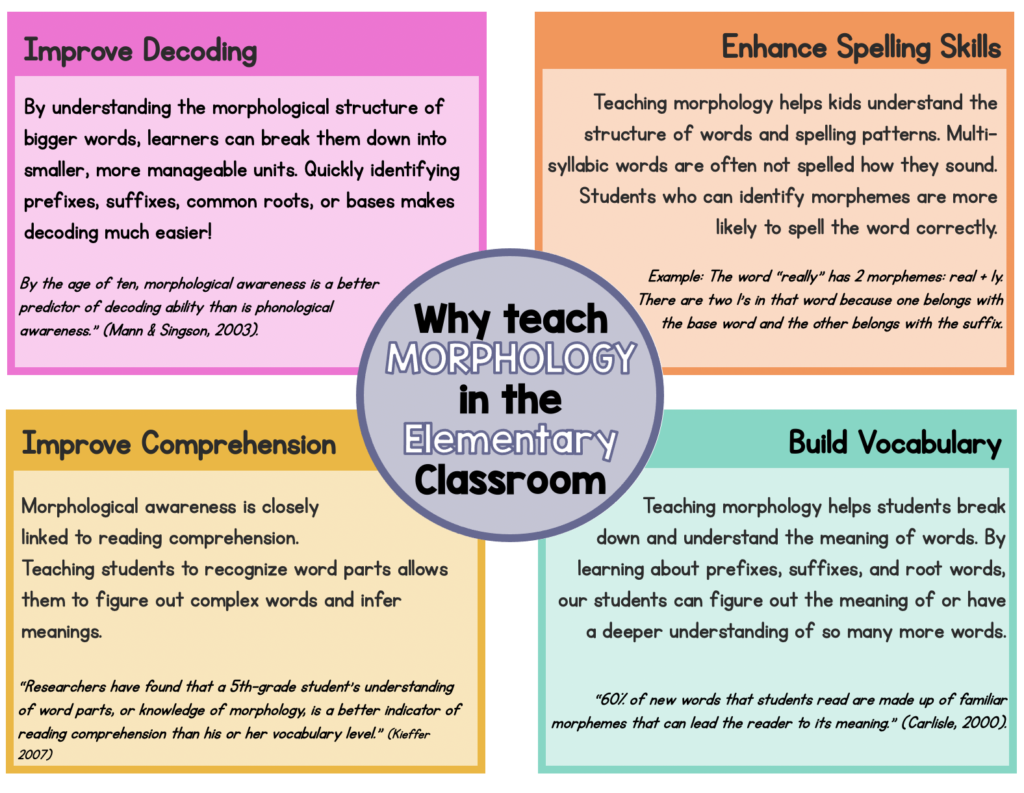

Understanding morphology involves exploring how words can be broken apart into meaningful units. Teaching morphology is beneficial for decoding unfamiliar words, expanding vocabulary, and enhancing language comprehension.

- Improve Decoding of multi-syllabic words: It is so helpful to be able to quickly identify prefixes and suffixes and common roots or bases while decoding. By the age of ten, morphological awareness is a better predictor of decoding ability than is phonological awareness. (Mann & Singson, 2003).

- Building Strong Vocabulary: Teaching morphology helps students break down and understand the meaning of words. By learning about prefixes, suffixes, and root words, our students can figure out the meaning of or have a deeper understanding of so many more words. For example, if our students know that the prefix re- means “again”, they can figure out that “rewrite” means to write again. “60% of new words that students read are made up of familiar morphemes that can lead the reader to its meaning (Carlisle, 2000).

- Improving Reading Comprehension: Morphological awareness is closely linked to reading comprehension. Teaching students to recognize word parts allows them to figure out complex words and infer meanings. “Researchers have found that a 5th grade student’s understanding of word parts, or knowledge of morphology, is a better indicator of reading comprehension than his or her vocabulary level.” (Kieffer et al, 2007)

- Enhancing Spelling Skills: Understanding the structure of words can really help with spelling! Teaching morphology helps students understand spelling patterns, making it easier for them to grasp spelling rules and exceptions. Multi-syllabic words often are not spelled how they sound. Students who can identify morphemes are much more likely to spell the word correctly. Here are some examples:

- If a student is struggling to remember how to spell the word “really” and keeps spelling it “realy” with one <l>, you can explain that the word is made up of two morphemes: base word “real” + suffix -ly. There are two <l>’s in that word because one <l> belongs with the base word and the other belongs with the suffix.

- Another example I like to use is the word “different”. It sounds like it should be spelled “difrent”. When we use morphemes, we can see that it is base word “differ” plus suffix -ent. When we say “differ”, we can hear that /er/ sound. There are endless examples like this one.

- When spelling the word “rocks”, a student may want to spell it like “box” or “fox”. Afterall, it does sound the same. The understanding that “rocks” is really “rock” plus suffix -s, meaning more than one rock can help with understanding of the word and spelling of the word. (See Instagram post explaining here.) This is a basic example, but it serves as a foundation for later understanding with more complex words.

- (Read more about spelling instruction here. )

English is Morpho-Phonemic

To wrap it all up… English words are made up of two components: phonemes and morphemes. English spelling represents sounds, syllables, and morphemes. Students need knowledge of both phonology and morphology to fully understand English words.

Although we must teach sound-symbol correspondences and spend ample time mastering decoding and encoding early on, we also should begin introducing the concept of morphemes. We want students to be thinking about structures along with pronunciation. Both are equally important.

Morphological elements are spelled consistently, even though the pronunciation will vary. Pronunciation can change as we add or take away affixes, but the spelling remains consistent. A schwa sound may move, the stressed syllable may change, and vowels may represent different sounds depending on the affixes you add. “Bases and affixes can have multiple pronunciations, but use consistent spelling to mark relations of meaning.” (Pete Bowers)

Pronunciation Changes, Spelling is Consistent

Let’s take a look at two examples of related words that change pronunciation, but keep spelling:

In this first example, see how the letters <e> and <a> change pronunciation. You can also see how the letter <t> represents the /t/ sound and then changes to /sh sound when combined with the -ion. The base here is “relate”. We add the suffix -ive to make “relative”. We add suffixes -ion and -ship to make “relationship”. The pronunciation changes but when we look at it through the lens of morphology, it’s easy to see the relationships. The only change in spelling was the consistent suffix rule of dropping e before a vowel suffix.

Now, let’s look at another example. Here the root is “nat”, which means “birth”. When suffix -ive is added, the <a> makes a long a sound and the <t> represents the /t/ sound. But, if you add -ion to the root, the letter <t> no longer represents the /t/ sound. Once you another suffix -al, the <a> changes from a long a to a short a. Add yet another suffix -ity, and that second <a> goes from a schwa sound to a short vowel sound and that syllable is not the stressed syllable. See how pronunciation varies so much but the spelling and meaning totally make sense! It’s like putting puzzle pieces together.

Irregular Words or Just Misunderstood Words?

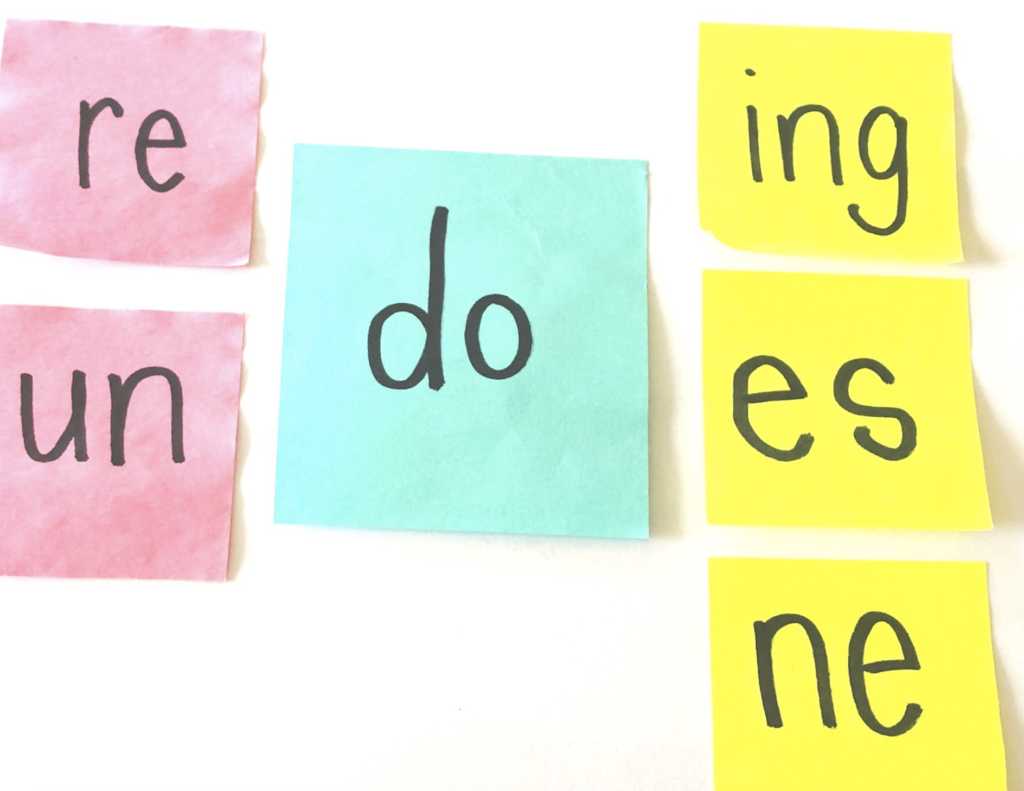

Here is another picture from an old post to illustrate the words “do”, “does”, “doing”, “done”, “undone”, and “redo”. Often the word “does” is super tricky for students and we consider it an irregular word. It does seem irregular if we are only considering the sounds in the word. If we were to do phoneme-grapheme mapping, we would break it up like this: d-oe-s with <oe> representing the /u/ sound. However if we were considering morphology, the spelling sure does make sense. The word “does” is base word “do” plus suffix -es. This is similar to “goes”. As with other words, the pronunciation changed when a suffix was added but the spelling remains intact.

The word done is base word “do” with suffix -ne (similar to “gone”). I remember reading somewhere that -ne is an irregular version of the suffix -en? That one is a bit trickier but super interesting! I’m sure there is a historical explanation.

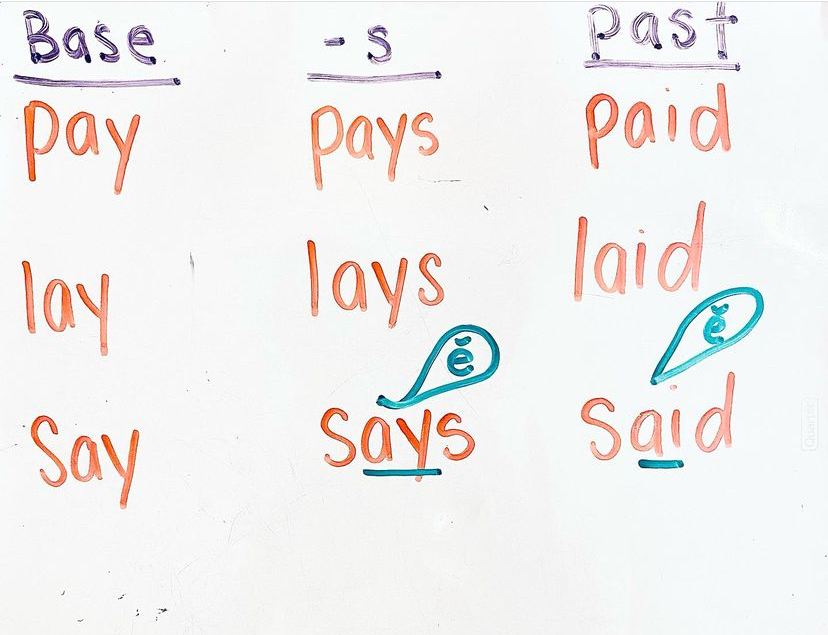

The word “said” has a similar structure to “paid” and “laid”. Pronunciation of “says” is different, but the spelling shows it is base “say” plus suffix -s. That’s much better than trying to “sound out” that word.

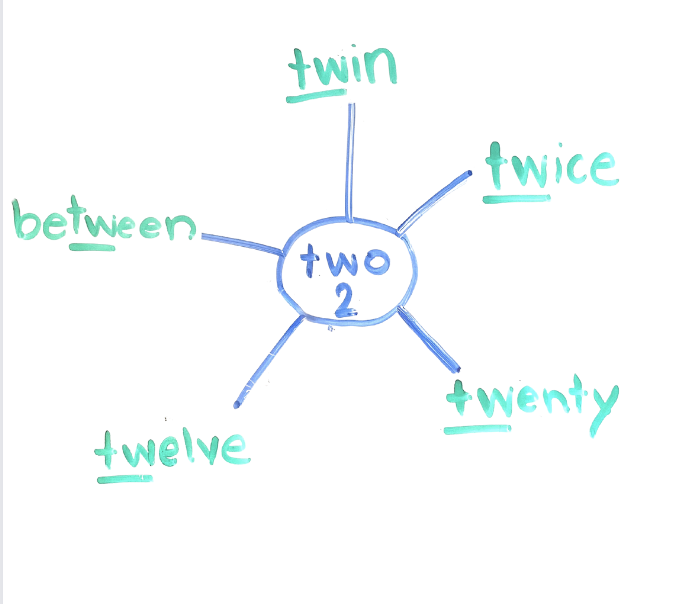

One last example is the word “two”. The <w> seems like it comes out of nowhere. Long ago, the /w/ may have been pronounced. The /w/ sound is still pronounced in related words, like “twin”, “twelve”, “twenty”, “twice”, and “between”. All are related to the meaning of two.

This all feels like a lot of information that may be too overwhelming to throw at our students. Well, you’re exactly right! It would be too much to just throw at them all at once. This is why we want to give little snippets starting early and continue to review and show more and more examples often! We start very basic and slowly add on.

So how do we do that? Check out my next blog post on how to get started with teaching morphology. Then, read the third morphology post about how to teach morphology in the intermediate grades.

Resources:

I’ve posted a few videos on YouTube that may be helpful. Click here to get to my morphology videos.

So far, I’ve created several resources for Latin roots and some suffix resources as well.

The first one is a digital resource that will lead you through teaching each root. The “Root Activities” pack is interactive and great for centers and small group instruction. The word matrices come as a digital Google Slides option and “printable” worksheet option. The reading passages area great way to work on fluency and vocabulary buildings. Finally, the root posters are super helpful visuals to connect to meaning of those morphemes. These are sold separately, or you can buy them at a big discount as a bundle!

Here is a link to all of my morphology resources.

Acknowledgements:

Eide, Denise. Uncovering the Logic of English: A Common-Sense Approach to Reading, Spelling, and Literacy. Logic of English, Inc., 2012.

Hegland, Sue Scibetta. Beneath the Surface of Words: What English Spelling Reveals and Why It Matters. Learning About Spelling, 2021.

Moats, L, & Tolman, C (2019). Excerpted from Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS): Module 4

Zafarris, Jess, and Marco Marella. Once upon a Word: A Word-Origin Dictionary for Kids: Building Vocabulary through Etymology, Definitions & Stories. Rockridge Press, 2020.

Home, www.wordworkskingston.com/WordWorks/Home.html. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.