Hello again! I meant to get this post up right after my previous post but life happened. 😉 My last post was all about what happens in the brain while we read. Make sure you read that post first before continuing on to this one. This one will make more sense if you read that one first.

After reading this post, you should also check out an older post about myths and misconceptions surrounding dyslexia. Knowing what dyslexia is NOT will help you understand what it IS. I am not an expert by any means. This has just become a passion of mine to learn more and spread any knowledge and understanding that I do have.

I encourage you to do some more reading and, if possible, take a class or seminar by someone who is an expert so that you can learn more! The research about dyslexia is there and there is a lot of it. We just need to get it out there so it is common knowledge for all educators. A great place to start is Overcoming Dyslexia by Sally Shaywitz.

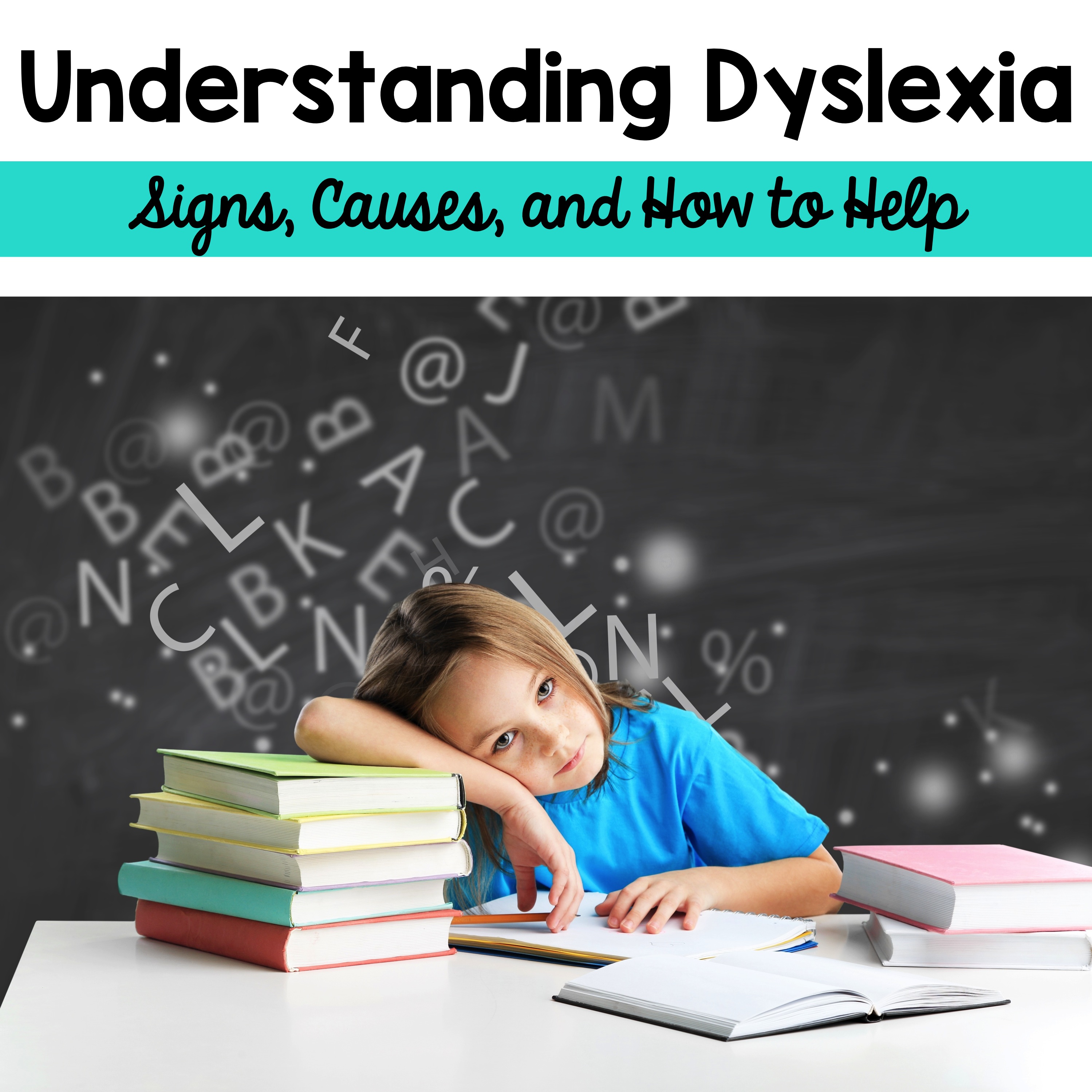

What is Dyslexia?

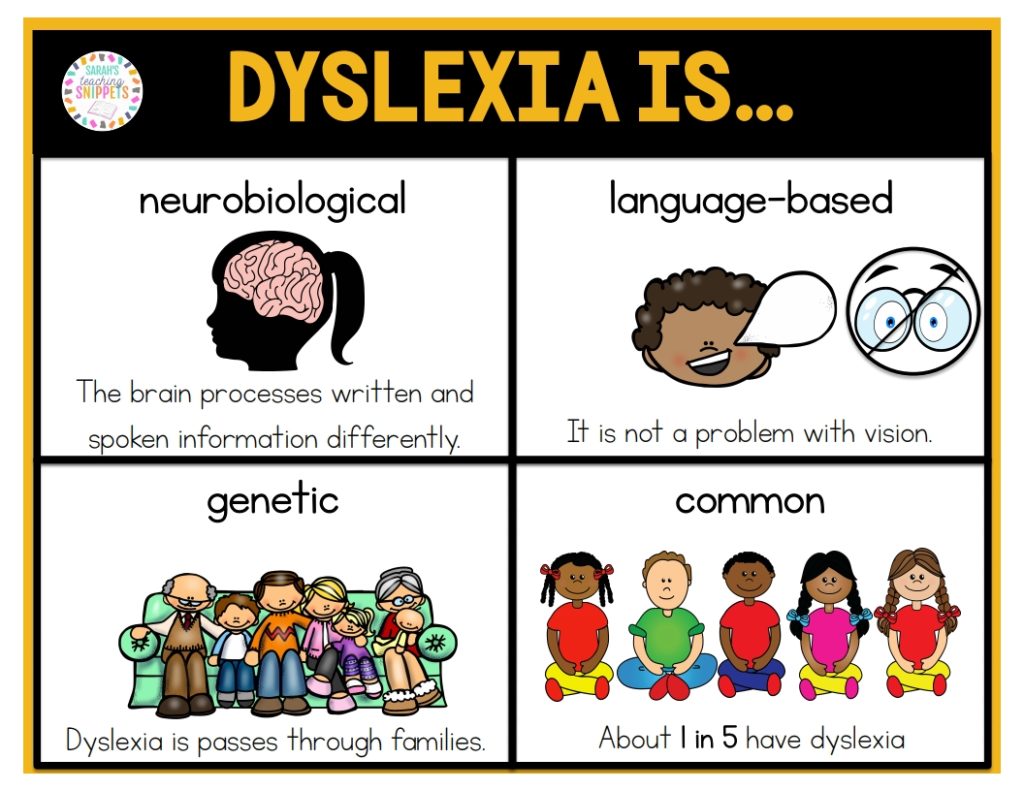

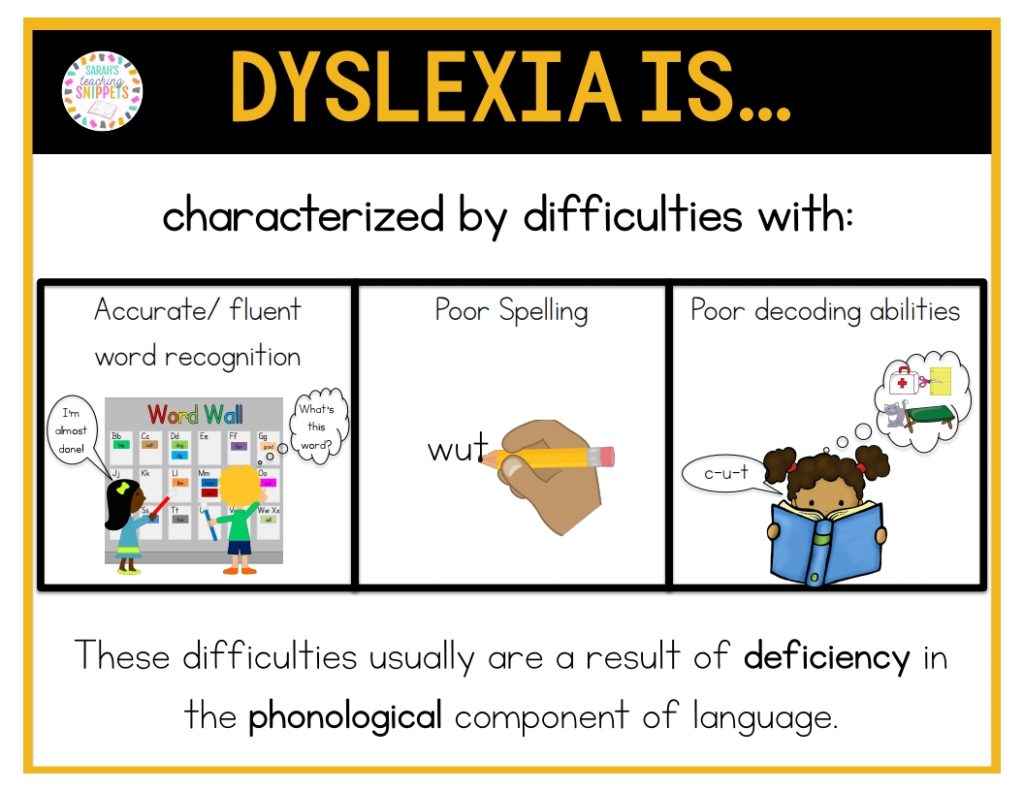

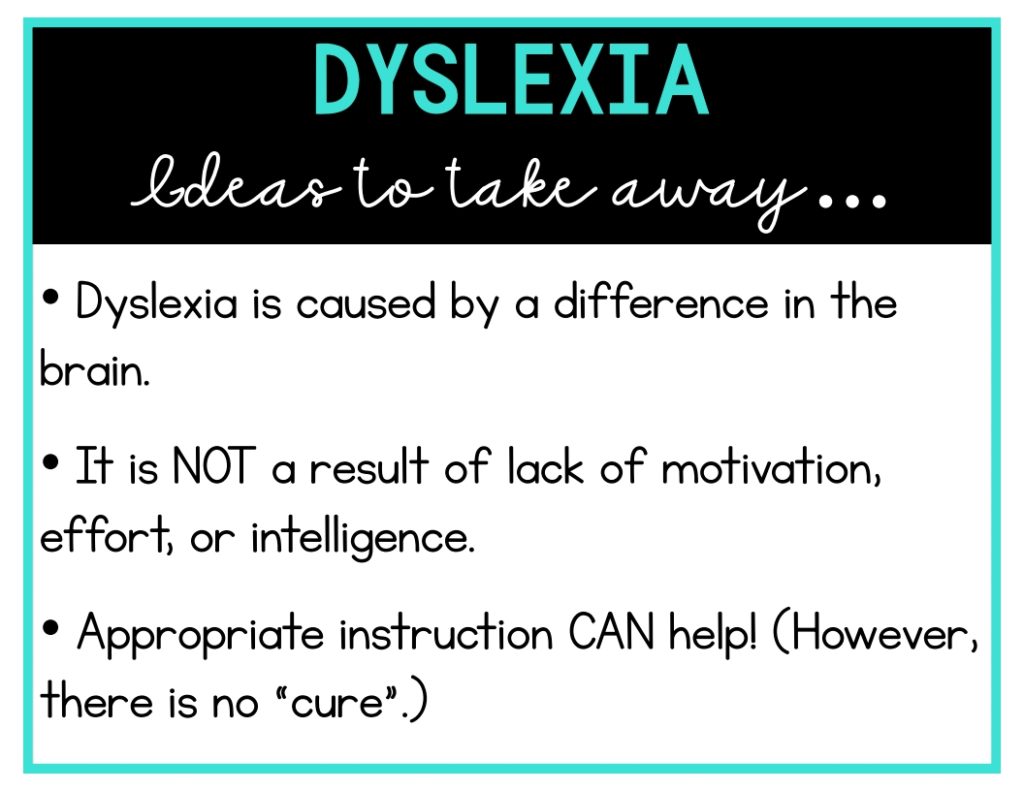

I made this visual to quickly get out a few things that are important to know about dyslexia. It is inspired by this definition from the International Dyslexia Association: Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. (IDA)

1. First, it is neurobiological. It is NOT from lack of effort or intelligence. There is a difference in the brain that develops before any formal instruction ever takes place. You will see below more about this.

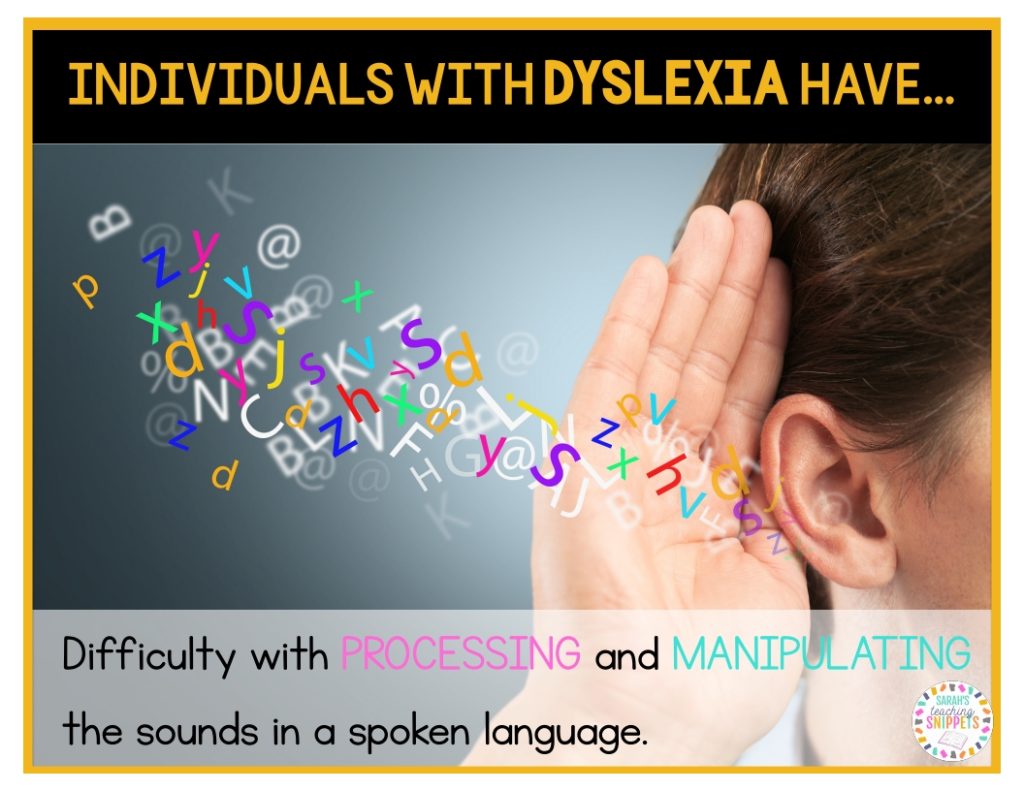

2. It is a language based disability. It is not a problem with vision. People with dyslexia have difficulty with language skills, including reading, spelling, writing, and in some cases, even pronouncing words.

3. Dyslexia is passed through families. When a child is struggling with reading, this is one of the first things I look for- family history. Many parents/grandparents might not know they have dyslexia but they will say they “had a hard time in school” or “don’t like reading” or “aren’t great readers.

- From Understood.org: “About 40% of the siblings of a person with dyslexia may have similar reading issues. Scientists have also located several genes associated with reading and language processing issues.”

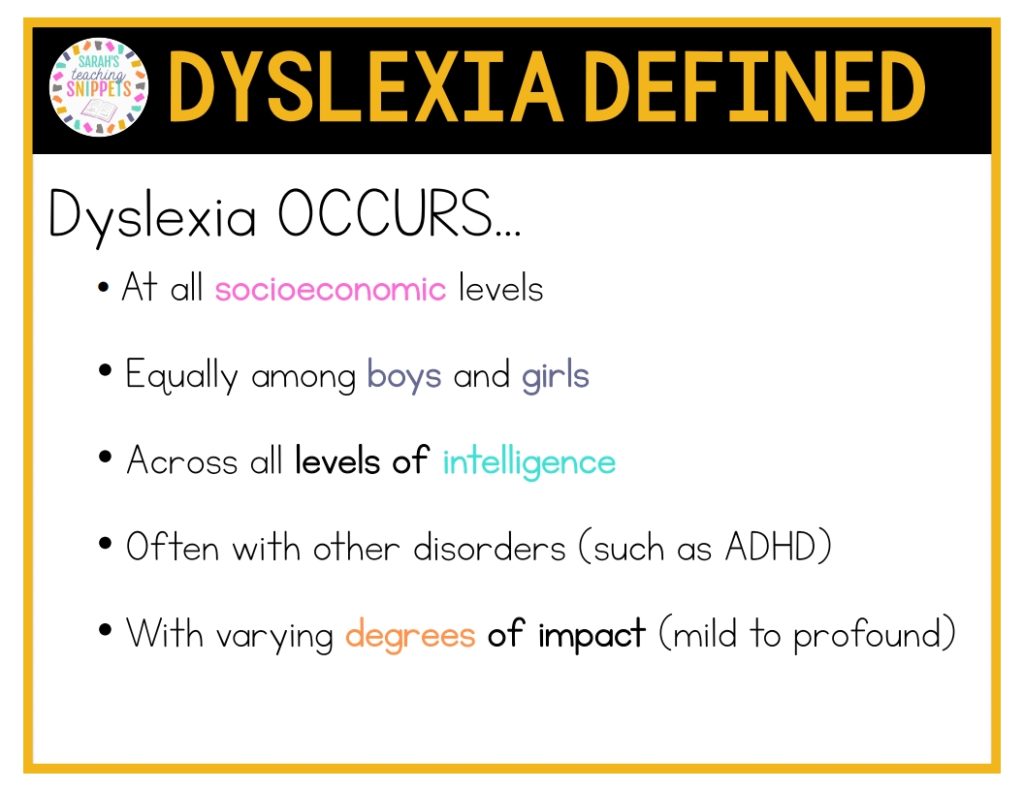

4. Dyslexia is more common than you realize. About 1 in 5 students have dyslexia. That means you most likely DO have a dyslexic student in your class. There is a wide spectrum of abilities and symptoms, so it is not always an obvious case. The more I learn about dyslexia, the more I see it. Think about it: If you have a class of 20, that means statistically, you have 4 kids who are struggling with this disability on some level. That’s pretty significant!

As I mentioned above, there is a pretty wide spectrum when it comes to the severity of symptoms. I started studying dyslexia when I had a student who was/is profoundly dyslexic. It couldn’t be ignored, even if I didn’t know what I was dealing with. By studying his severe symptoms of dyslexia, I started to see the same symptoms in students who weren’t struggling as much as he was. Now after years of knowing what to look for, I can see how truly common it is.

This is the first thing I look for. When a student is struggling with phonemic awareness in kindergarten/early 1st grade, that is a red flag for you. I start working with kids in kindergarten who are struggling with phonemic awareness. Some of them turn out to be totally normal readers. Others improve with intervention, but are identified later with dyslexia. The early intervention is significant for students with and without dyslexia because phonemic awareness is one of the main indicators of reading success. (See my post on phonemic awareness.)

I think sometimes people think since I work at a private school, there must be no struggling readers. WRONG! Since dyslexia is the result of a difference in the brain, it can affect people from all backgrounds and economic situations.

- It does not go away just because your family has read to you since birth. I’m going to repeat that one because I have many parents who say, “But I read to them every night of their whole lives!”

- Reading to your child does not prevent dyslexia. It is neurobiological, remember?

- Let me be clear though- being read to as a child is still incredibly important. It develops comprehension, vocabulary, language skills, and (hopefully) a love of literature and learning. From what I understand, it won’t prevent dyslexia, though.

- There is a difference between children struggling to learn to read because of background, opportunity, instruction, or circumstance and children struggling because they have dyslexia.

I was also surprised to learn that dyslexia is equal among boys and girls.

- *Update*: I recently read an article that is disputing this fact, saying that actually, boys are more likely to have dyslexia. Sounds like more research is needed on this one because I’ve read conflicting research now. In my own experience, it’s been pretty equal among boys and girls.

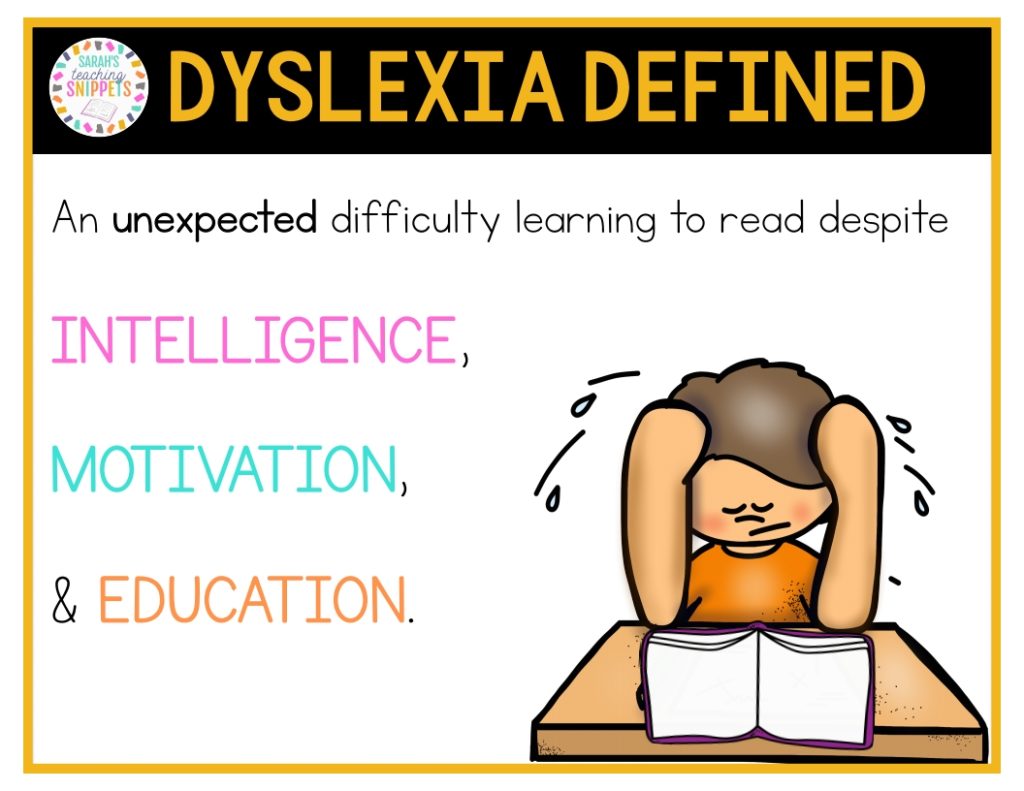

It’s also important to remember that dyslexia has nothing to do with intelligence!

- In fact, dyslexics have average to above average intelligence. That’s actually part of the definition. The best simple definition I heard was from PDX Reading Specialist. I don’t know if she made this up or heard it somewhere else, but I’m giving her credit. This definition is simple and really sums it up.

Causes of Dyslexia

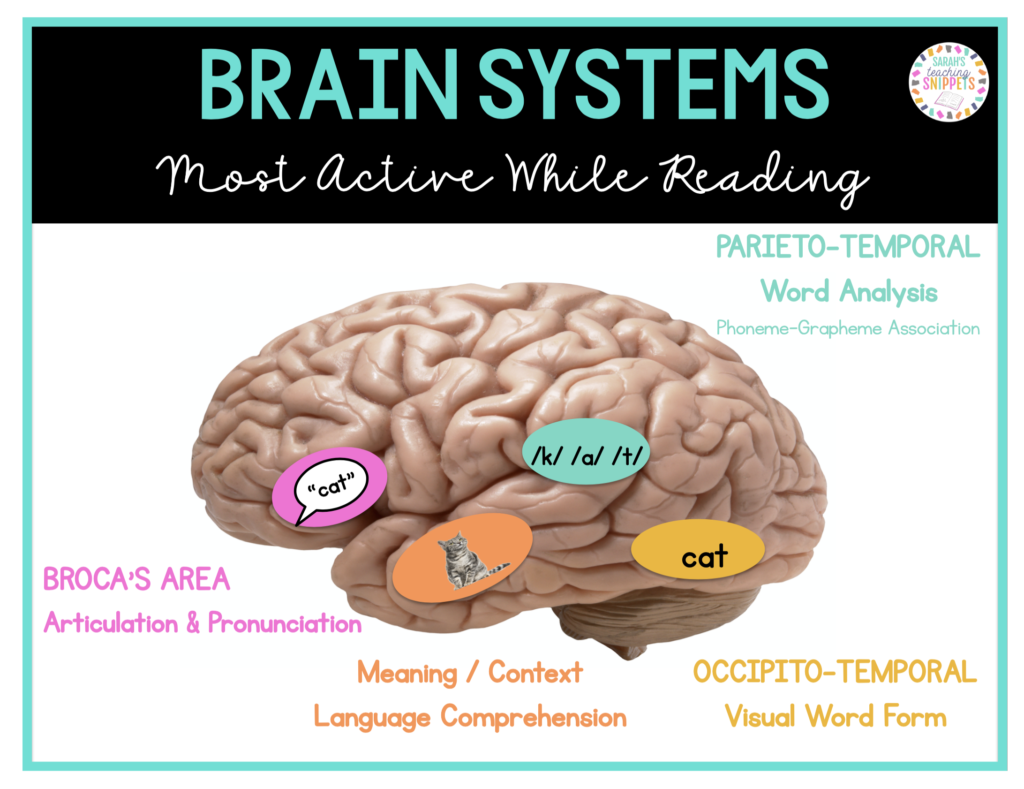

Now that we’ve looked at what dyslexia is, we can look at some of the reasons why students struggle with this disability. Let’s look at the brain! Disclaimer: I am not a brain scientist or an expert in any way. I’m simply taking information I’ve learned and sharing it with you all. First, let’s review one slide from my last post. Make sure you read that one first.

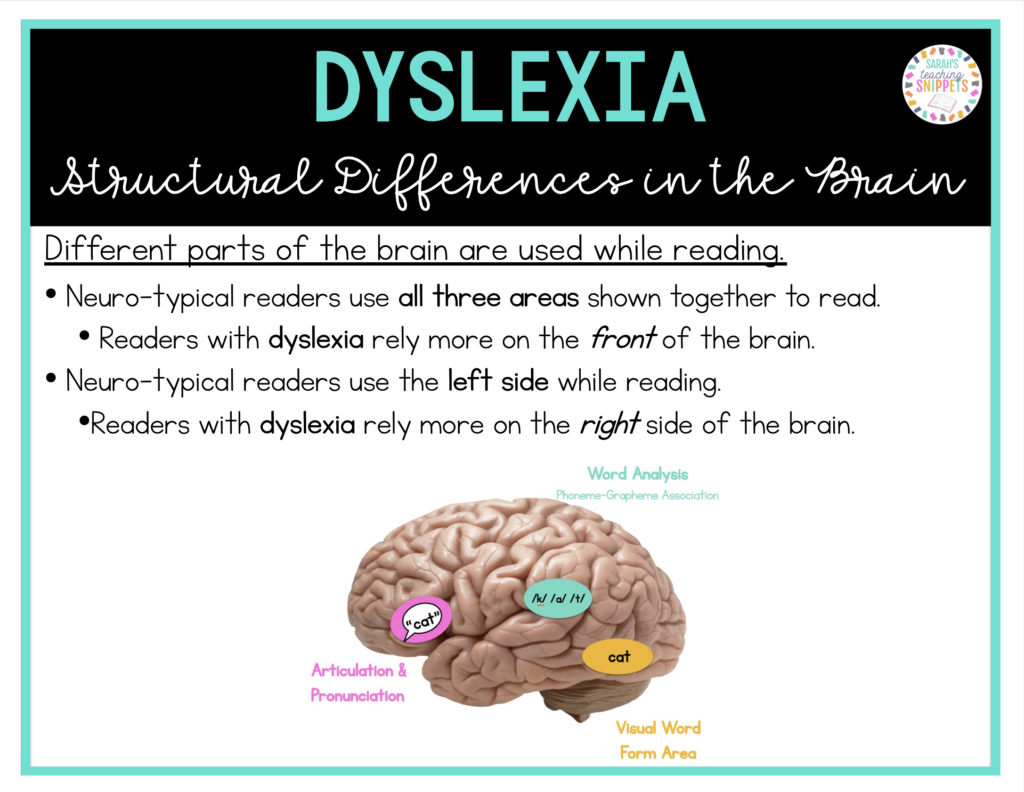

My previous post talked about the different roles each of these systems play. To explain what happens in the brain of a dyslexic reader, I am focusing on the three that have to do with decoding.

(Sorry, these two slides basically say the same thing, but I’m so visual and indecisive about which is better.)

Remember that each system plays a part. They all work together to make reading a smooth process.

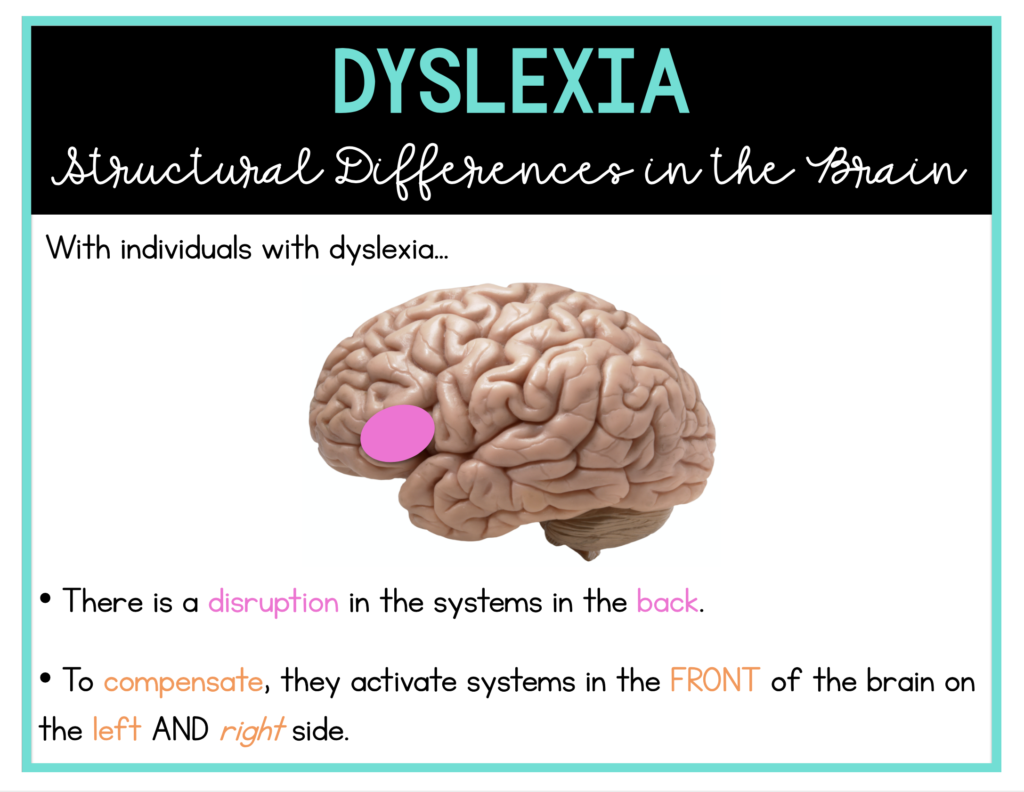

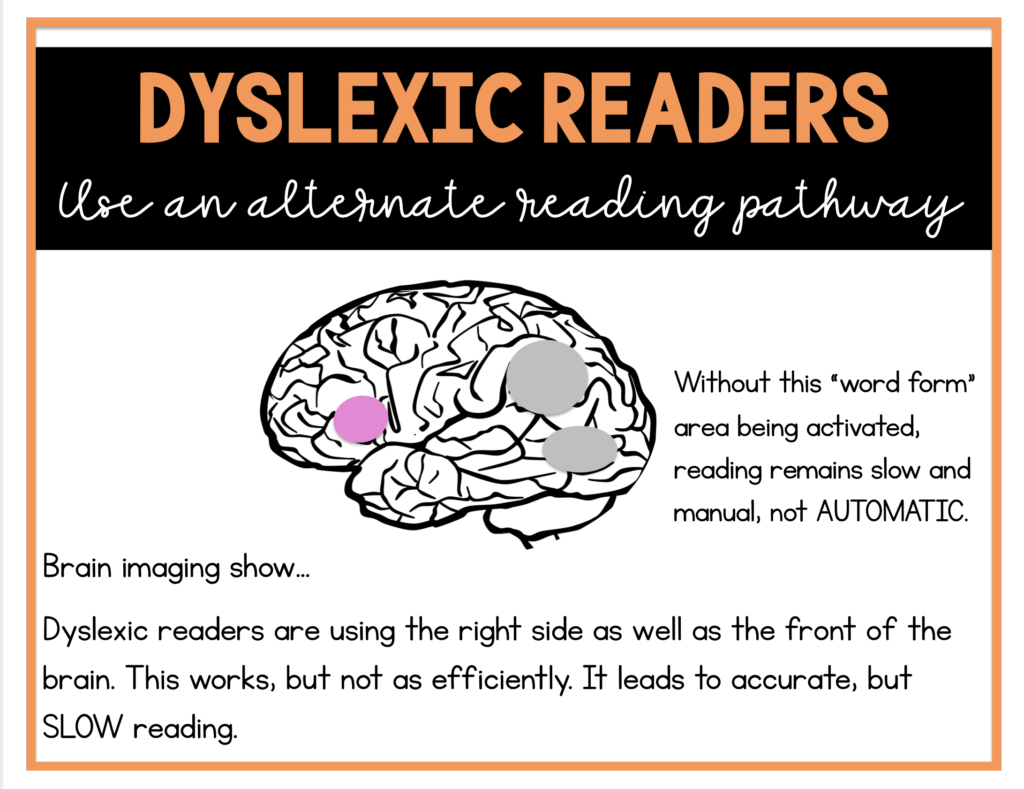

Notice how they don’t develop that left-side word form area, which leads to fluent reading. This area is the place where word retrieval becomes automatic.

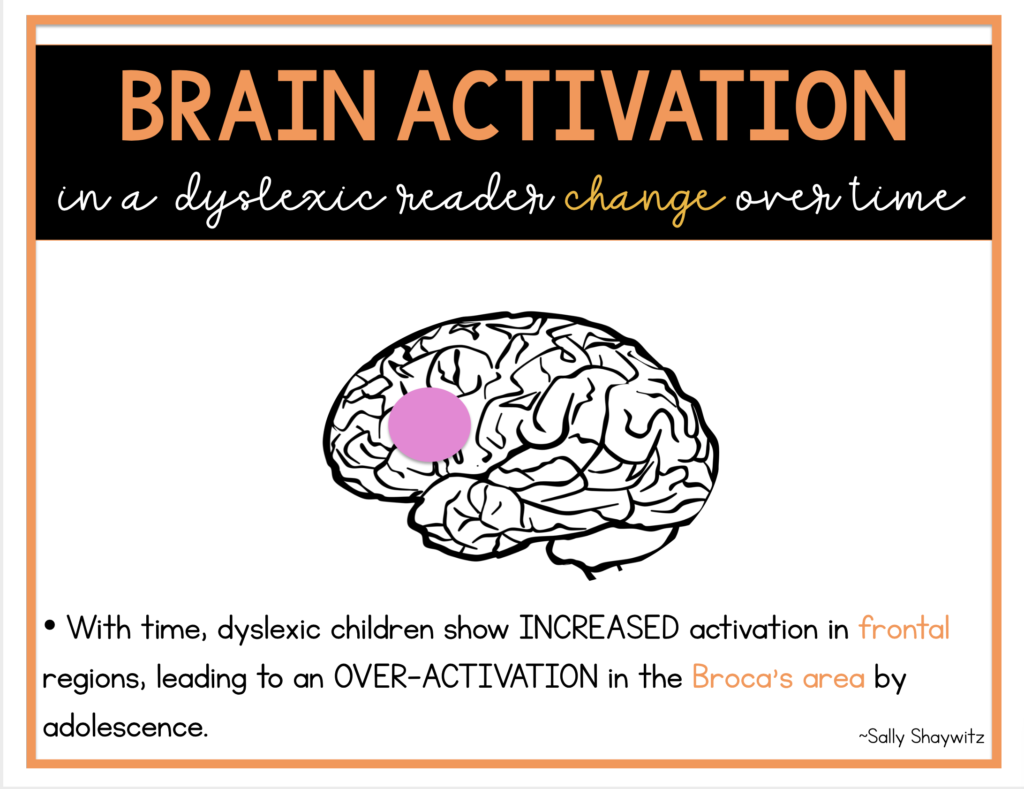

To read a word, individuals with dyslexia take a longer path through the brain. They can get delayed in that slow, analytic frontal part of the brain.

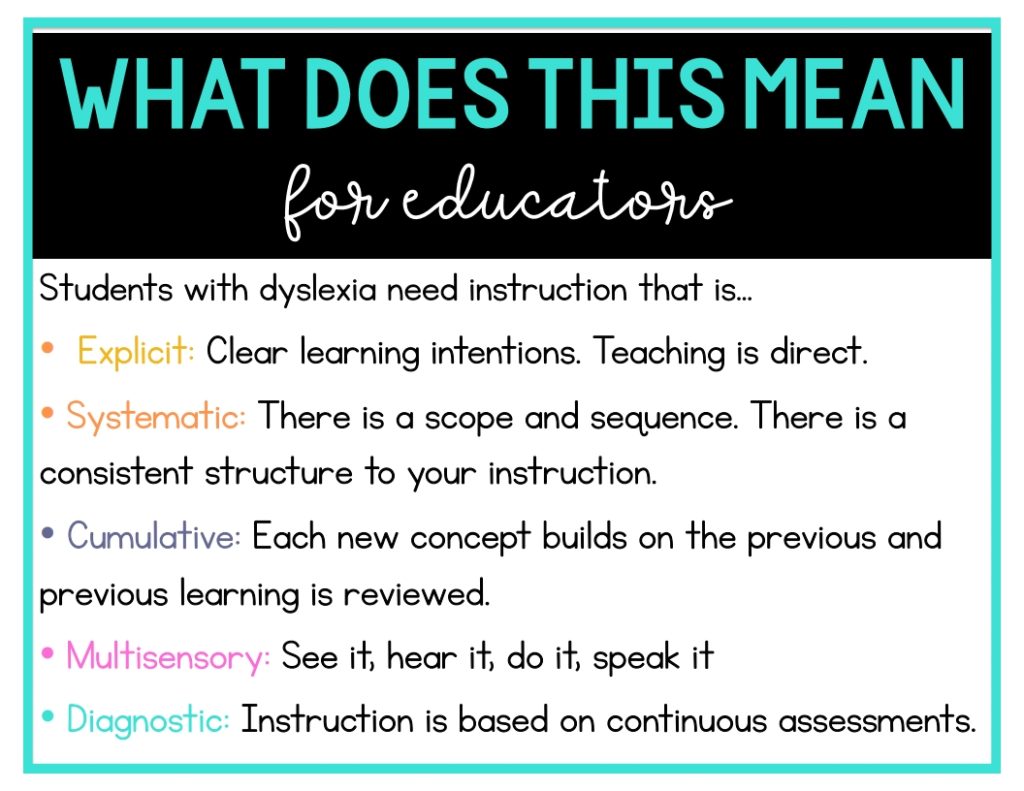

New research has found that with appropriate instruction, we can begin to form new pathways for our dyslexic readers. That’s why appropriate instruction is so important. (My next post will go into this more.)

Signs of Dyslexia

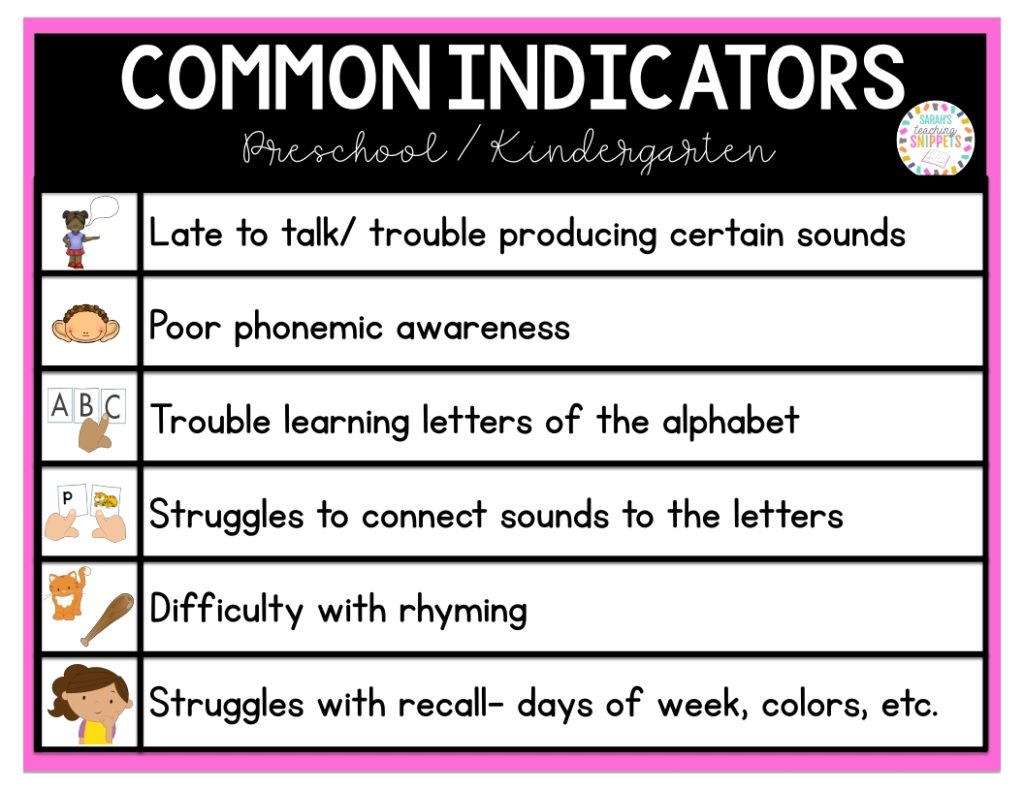

Now let’s look at the warning signs of dyslexia. When I see these symptoms, I’m not about to go diagnosing anything. (There are specialists for that.) I will, however, start giving them support they need. Early intervention is key!

I don’t work with preschoolers, but I do work with kindergartners. When a student is struggling to learn the alphabet and seems to forget a letter from one day to the next, I start intervention.

When a student struggles with phonemic awareness, I start doing activities right away to develop that. Phonemic awareness activities should be fun! Every kindergarten classroom needs to have daily activities. These are simple and short activities. If a student isn’t picking up these skills by mid-kinder, that’s when I start intervention with them. It’s still fun, simple activities though.

I think the biggest warning sign for me is a student in mid-kinder who seems very bright and interested in learning, but struggles to remember their letters, days of the week, and other common things like that. If they are doing their little kinder journal and you see that they avoid sounding out words (instead they look around and only write words they can copy) or if they do try but it seems very difficult despite many opportunities to practice, I would look more into that.

(Note: If kids come into your kinder class without literacy at home- no books, not read to, no instruction with letters prior- that is a different story usually. They need more exposure first before you can decide if it’s a red flag. However, you would give them the same RTI at this point because you need to get them exposure.) The intervention for a student who potentially has dyslexia is the same as the intervention you would give any student who is behind with reading or pre-reading skills. In fact, that type of instruction is good for all readers.

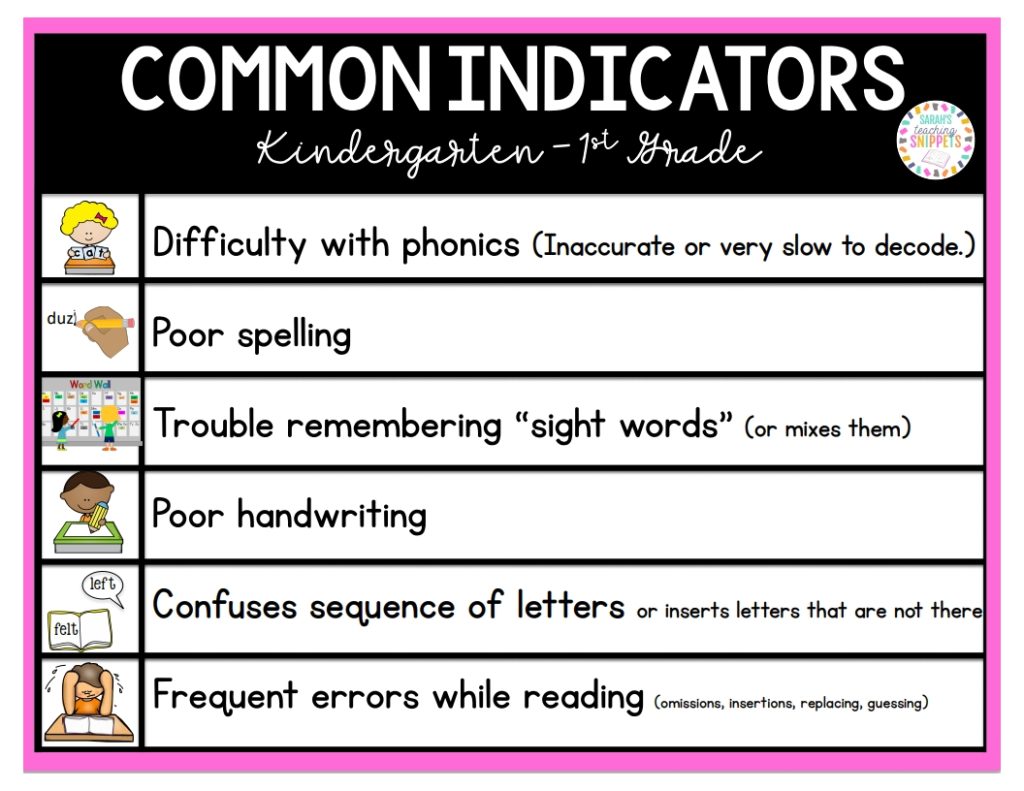

I can usually tell that a student may be struggling with dyslexia by mid/late first grade.

- If they are still really struggling with decoding or remembering sight words, that is a huge red flag.

- Poor spelling is still pretty common in first grade, but becomes a bigger red flag later.

- One of two of these signs alone are not red flags.

- Many kids have poor handwriting. This alone is not an indicator.

- Also, it’s important to note that when kids are first learning to read, they will make errors. However, frequent errors after the student has been working on reading for a while (mid-usually late first grade) may be an indicator.

- I just look at all of these signs when I’m starting to wonder about a student. The biggest thing to look for is difficultly with phonics and/or learning sight words.

- I also look out for those kids who can memorize any sight word you put in front of them so they “word call” while they read. They can mask their disability. They sound like they are reading, but then you give them a word they don’t know and their decoding skills are very poor. That is a red flag. They are memorizers, but are not actually reading. They must decode.

- These kids tend to have poor spelling because they can read those sight words well, but usually mix up letters when spelling those same words.

- I think the most common symptom is the problems with decoding. You’ll get those kids who (by first grade) know their letters and the rules of phonics but they decode SO slowly. They sound out the same word on every page. They don’t notice word families and other patterns that may help them. This is a red flag (after proper instruction and exposure.)

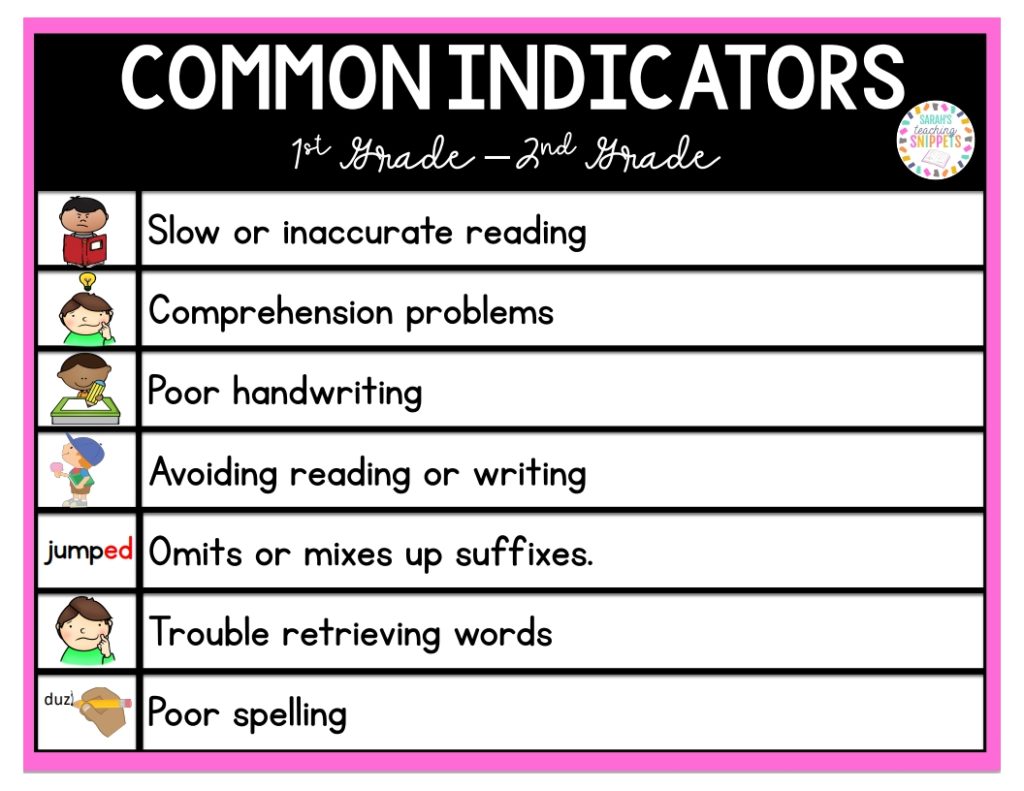

This is when spelling becomes a bigger red flag. Fluency is also a biggie. Comprehension problems are usually a result of the slow or inaccurate reading. These are kids that may have excellent comprehension during read-alouds but not when they read on their own.

Third grade is usually the time where dyslexics hit a wall. If they were able to compensate with or hide their disability in the earlier grades, they usually can’t anymore. That’s because there are so many more words! They can’t memorize every word anymore. Multi-syllable words become common. So many words look the same. Advanced decoding is necessary.

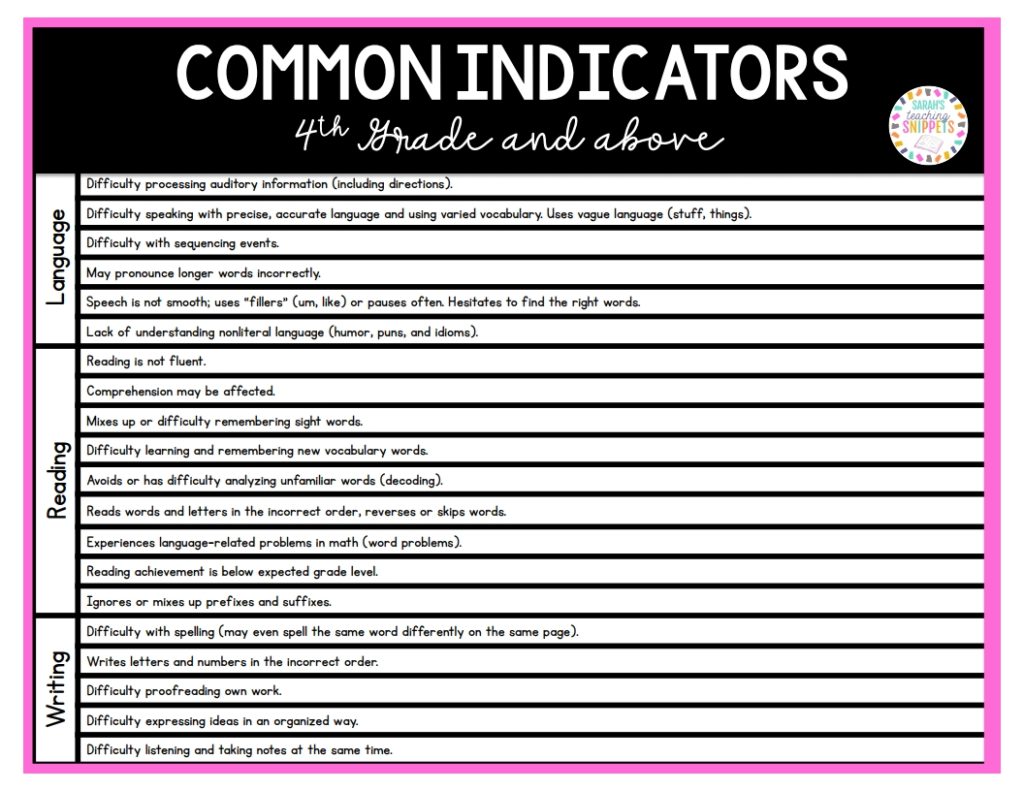

It’s important to remember that dyslexia is not a one-size-fits-all. If you have met one student with dyslexia, then you have met one student with dyslexia. Dyslexia can look so different with each student. Remember there is also a spectrum, mild to more severe. By the time a student is in 5th grade, if they have mild dyslexia, they may be reading okay, but they may really struggle with spelling or their reading might be slower still.

Testing for Dyslexia

The good news is you don’t have to be the one who determines if a student is dyslexic. It’s important that you know what to look for so that you can recommend further testing and evaluation, if needed.

The International Dyslexia Association has information about testing and evaluation. You can read that here.

Learning Ally is a wonderful website that provides audiobooks for students with dyslexia to give them access to books at their intellectual and interest level. They have a way to search for reading specialist in your state that have experience with dyslexia.

I think it’s also important to note that you shouldn’t need a “diagnosis” to provide accommodations and support for a student who is struggling with reading, writing, and/or spelling.

Although as teachers we cannot diagnose dyslexia, there are screeners that we can use to see who may be at risk for reading difficulties. I’ve always used DIBELS.

Recap

Click here to learn more about Structured Literacy, an instructional approach to teaching students to read that encompasses all of the elements of language and has key principles that guide how it is taught. Initially I started using a Structured Literacy approach for my students with dyslexia, then I quickly realized this is the best way to teach ALL students.

More about Dyslexia

International Dyslexia Association

Click HERE to visit the website for the International Dyslexia Association.

UPDATE: I just found this handbook created by the IDA. Great resource for families!

Free Printable About Dyslexia

Click HERE to join my newsletter to grab these FREE printable resources.

To read more about dyslexia click here.

More Posts about Dyslexia

This will lead you to all of my posts relating to dyslexia, including myths about dyslexia, how the brain reads, and effective strategies for teaching students with dyslexia.

Acknowledgements

I hope this post was helpful! My information came from these resources.

Posts Coming Soon…I would love to do a post on this book once I’m done with it:

In the meantime, check out this blog: The Dyslexic Advantage.

The mission of Dyslexic Advantage is to promote the positive identity, community, and achievement of dyslexic people by focusing on their strengths.

Um, yes please! I LOVE that research is coming out about all the strengths associated with dyslexia. I definitely need to work on a blog post about that!