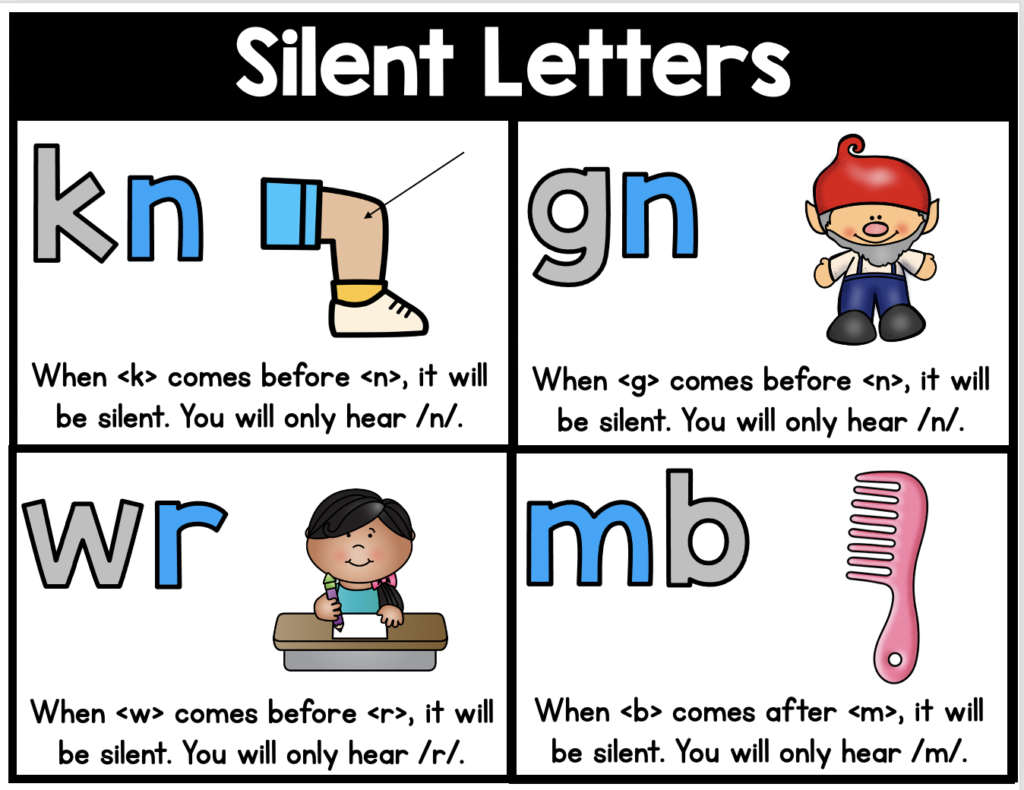

Teaching silent letters can be tricky! Silent letters appear all throughout the English language. The most common combinations are wr, kn, gn, and mb. Although I’ve seen that it is common to teach these all at once as “ghost letters”, I actually teach silent letters at different times. Surprisingly, students do tend to catch on very quickly to silent letters. In this blog post, we’ll explore strategies for teaching silent letters to elementary students.

What are Silent Letters?

A silent letter is a letter in a word that is not pronounced when the word is spoken aloud. Despite being present in the spelling of the word, silent letters do not contribute to the word’s pronunciation. Instead, they often serve historical or etymological purposes, reflecting changes in language over time.

Letters are written representations of sounds. When we are first teaching letter-sound correspondences, instead of saying “g says /g/”, we want to shift to saying “g can represent or spell the /g/ sound”. This leaves the door open to other pronunciations and times when it does not spell /g/. Although letters mainly represent sounds, in some cases, they can be silent markers. The most common example of this is the silent e. It is a silent marker that gives the reader information. Silent consonants can also be silent markers, but the information they are providing may not be as obvious. 😉 They are marking connections to other words or a word’s origin.

Silent consonants and vowels can occur at a word’s beginning, middle, or end. This blog post focuses on the common silent letter combinations kn, wr, gn, and mb.

- In the word “knee,” the <k> is silent, so <kn> is pronounced /n/.

- In the word “write,” the <w> is silent, so the <wr> is pronounced as /r/.

- In the word “gnome,” the <g> is silent, so the <gn> is pronounced as /n/.

- In the word “comb”, the <b> is silent, so the <mb> is pronounced as /m/.

Why are these letters silent?

Before teaching these silent letter combinations, let’s provide a little background about why these letters are silent. It’s really interesting, and it shows that English isn’t as “crazy” as it seems. Explaining to students why certain letters are silent can make it more accessible to them because it doesn’t feel so random.

At one time, they may not have been silent

In many cases, silent letters were at one time not silent! They DID represent a sound. These common letter combinations were not consonant digraphs (where two letters represent one sound). They were consonant clusters, where both consonants represented a sound. Over time, one of the sounds was dropped, but by that point the spelling was set. Pronunciation shifts are very common over time.

I always tell my students that when they see a word with a silent letter, that usually means the word is very very old! For example, <wr> was a “common Germanic consonantal combination” (etymonline), especially with words implying twisting or turning (see below). In Old English, the /w/ sound was pronounced. Eventually, it faded away, but the spelling was intact.

The <k> is <kn> was also a common consonant cluster where the /k/ was fully pronounced in Old and Middle English. (Interestingly, it was <cn> in Old English and changed to <kn>.) Again, we see an example of a sound fading away but the spelling was already in place.

One way to explain why maybe these sounds faded over time is to challenge my students to say these words with both consonant sounds. It is quite difficult!

Silent Letters give us insight into a word’s meaning or origin.

Silent letters can give insight into a word’s meaning or origin. For example, the word “doubt” comes from Latin’s “dubitare” and is related to “dubious.” Around the 15th century (when many English spellings were not yet solidified), writers and printers wanted to show readers that most words originated in Latin and Greek, so they inserted these silent letters. On the History of English Podcast (episode 153), Kevin Stroud explains that many writers and printers were interested in where words came from and how they were related to each other. These writers and printers knew the Latin origins of words, and they wanted the spellings to reflect the etymology of a word. For this reason, they would sometimes add in a letter to represent a sound that had disappeared over time.

Silent Letters show us connections to related words

Silent letters may also show us connections to related words that may share a root. For example, in “sign”, we do not pronounce the /g/ sound, but we do in “signal” and “signature”. We also do not hear the /b/ in “crumb,” but we do in “crumble”. (Side note that <b> is only silent in <mb> combination when it comes at the end of a word.) It is helpful to show our students these connections. These silent letters are considered “marker letters” because they mark the relationship to other words.

The Word may come from another language

English has borrowed many words from other languages. The word “yacht” is the perfect example. The English language has been very open to adopting words from other languages and sometimes the spelling remains in tact with no changes.

Mystery Reasons

According to Etymoline, “the unetymological -b began to appear late 1500s for no etymological reason. So it seems we may not have all the answers yet. According to Kevin Stroud, one of the theories is that “thumb”, “limb”, and “crumb” got their silent b because the word “dumb” (which was from Old English) had a <b>. Scholars may have just assumed those letters needed the <b> for etymological reasons when, in reality, they did not.

Some Silent Letter Combinations Hold Meaning

Interestingly, the silent letters <wr> and <kn> not only contribute to the pronunciation of words but also hold meaning themselves. The <wr> combination often (but not always) indicates twisting or turning (wrench, wring, wrap, write, wrestle, wrinkle, wry, wreath). The <kn> combination has words related to the meaning sharp or pointy (knife, knit, knight, knee, knuckle) or they have to do with body joints (knee, knickers, kneel, knuckle, knock, knead, knelt, knit). Explaining this to your students can help them possibly distinguish when to use these silent letters in spelling. At the very least, it’s just an interesting tidbit to share with them!

When you are working on words with these silent letters, it is fun to challenge your students to think about connections to these meanings.

How to Teach Silent Letters:

Connect to the sound and Set the stage: I begin by orally saying some familiar words that use that grapheme. I may say, “What sound is in all of these words: wrestle, wreath, wrap, write”. They will say /r/. Then, I will say that these words all begin with the /r/ sound, but they do not begin with the letter <r>. I tell them that today we will learn another way to spell the /r/ sound.

Introduce Grapheme: At this point, I point to each consonant and ask for the sounds they usually represent. (For example, I would point to <w> and <r> and students would say /w/ /r/.) Then, I tell them that when these two letters are next to each other in this order, they will represent one sound: /r/. I explain that this is a common grapheme that represents the /r/ sound. The <w> is silent. I display a new tile with both of the letters together. Since they make one sound, they share a tile.

I like to spend a couple of minutes telling my students that the <w> was not silent long ago. We get a chuckle about how difficult it is to pronounce those two sounds together and say, “No wonder one of the sounds got dropped!” I push the <w> and <r> tiles aside and introduce the new tile, <wr>. I reinforce by saying, “When you see <wr> next to each other in this order, it will spell /r/.

At this point, I also tell them the cool “secret” that lots of words with <wr> have a meaning that has to do with twisting or bending. I challenge them to find those connections with the words we read and spell.

Spell Words with the New Grapheme

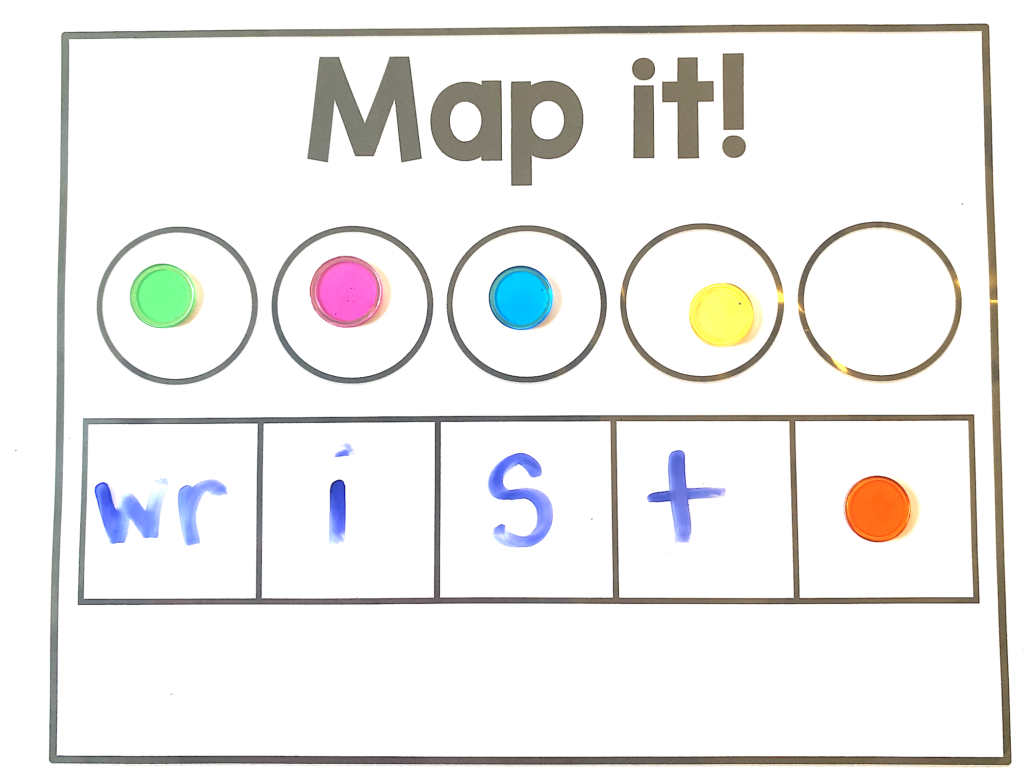

Next, we spell some familiar words with this grapheme. I use steps for phoneme-grapheme mapping to show how the sounds and letters match up. Begin with a word like “wrap”. (When I’m modeling for my students I like to use magnets to represent sounds. I tap the magnets as I say each sound.) I am explicit while I’m modeling by saying, “Normally, when we hear the /r/ sound, we use the letter <r>. This is one of the words where the grapheme <wr> is used instead.” After spelling the word, I point out the connection to twisting or bending. (When you wrap something, you are twisting and bending something around something else.)

After modeling, I do guided practice with my students. They use white boards or a sound box board like this one (placed in a sleeve protector so they can easily erase). I say a word, and together, we segment the sounds. I tap my magnets and students move the chips out of the squares and into the circles. (If you don’t want to mess with chips, kids can simply tap the circles with their finger.) Then I ask, “What is the first sound you hear? If it is not the letter <r> on its own, how can you spell /r/?” Students will write <wr> in their box and then they will finish the word. I continue in this way with more words.

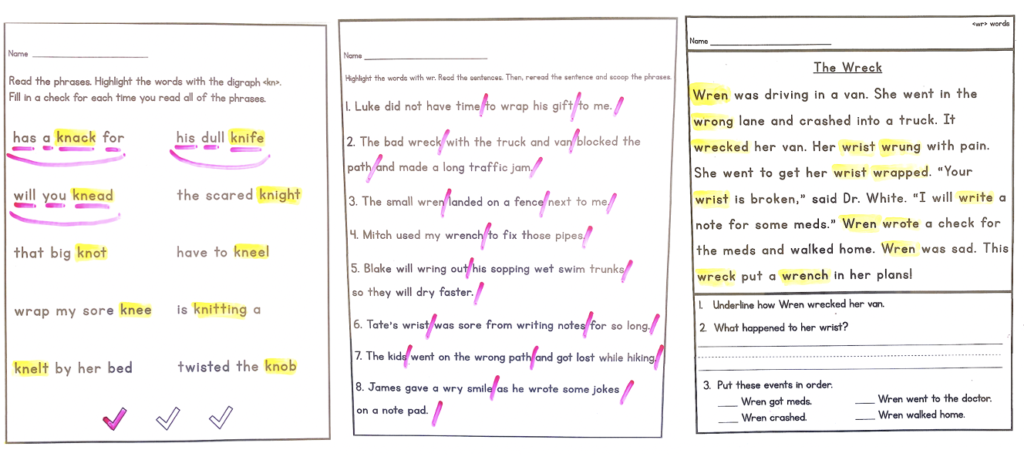

Practice Decoding Words with Silent Letters

After introducing the grapheme with a silent letter and spelling a few words with that grapheme, model and provide practice with decoding words. Write a word. Before reading it, ask “What sound will the letters <wr> make?” To make sure you have full participation, have students “whisper read” the word on their own first. Then give a signal for everyone to say the word.

After reading the word, go back and underline the graphemes in that word as you say the sounds.

Reinforcing Through Practice

As with any new concept, practice is key to mastery. Provide students with plenty of opportunities to practice reading and spelling words with the silent letters. I do not expect my students to be able to distinguish between <r> and <wr> or <kn> and <n>. Instead, I practice those in isolation (so my students know the words will be <kn> and not <n>). You can, however, practice spelling with <wr> and <kn> together since they represent different sounds. By the time you teach <kn>, it will have been a while since you’ve taught <wr>, so you can add those in during spelling as a review!

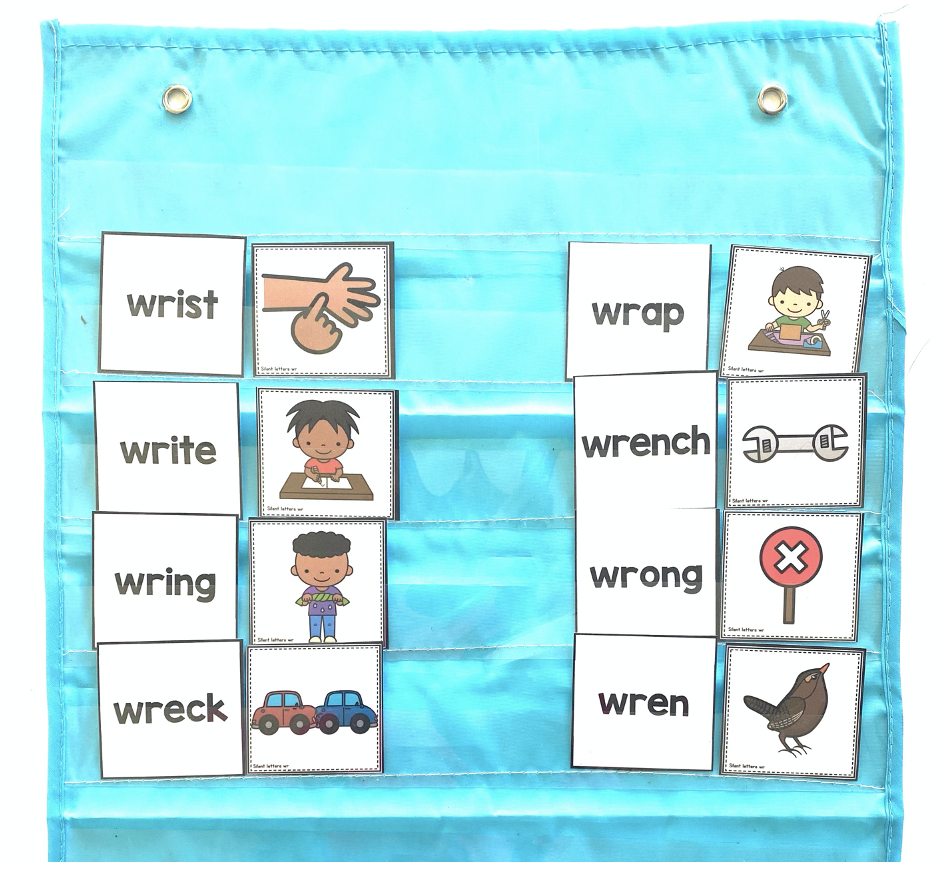

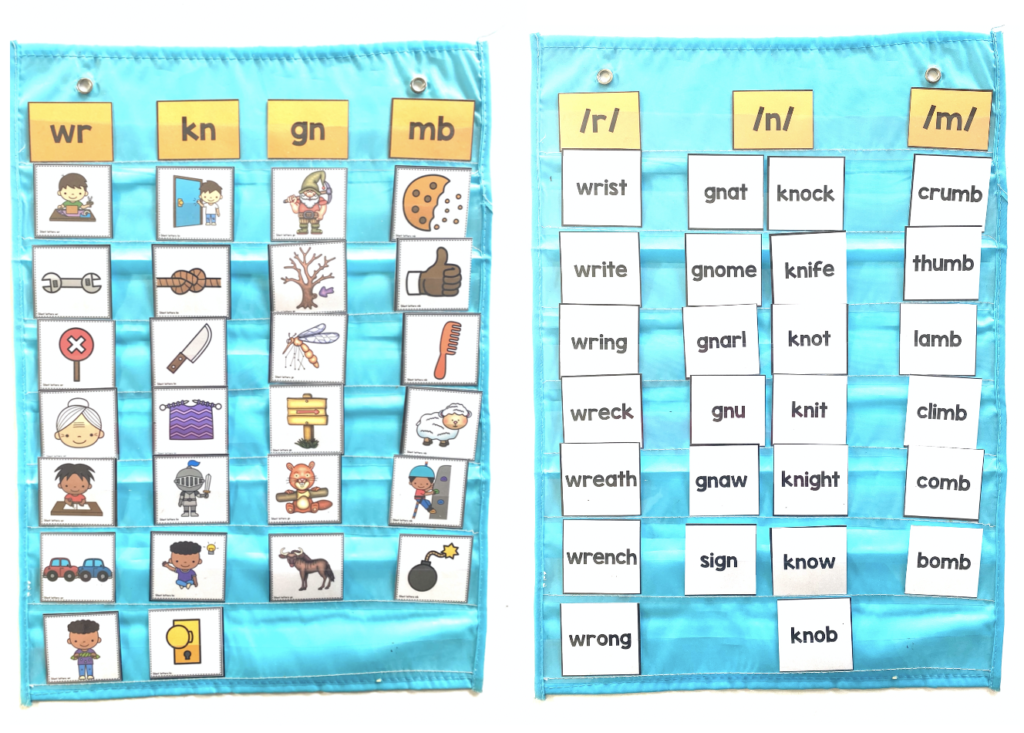

This simple activity is great for a small group of independent practice. Begin with the picture cards in the pocket chart. Have your word cards in a pile. Choose a word card and show the group. Instruct them to whisper read the word. Then, when you give the signal, have them say the word out loud. Find the matching picture and set it in the pocket chart. Connect to meaning by using the word ina sentence. You can also use this opportunity to connect to the meaning of “twist” or “turn”. You can discuss how the word’s meaning may involve the twisting and turning of something. (Note that not all are connected, like “wren”.)

As with every new phonics skill, we begin at the word level but quickly move to reading phrases, then sentences and passages or books.

These are examples from my Silent Letters resource.

Bring in Word Relatives

As I mentioned earlier, some of these silent letters show the reader relationships to other words. For example, crumb has a silent <b> but you hear that /b/ sound in related words crumble, crumbling, crumbles. It can be so helpful to point this out to students. It may help them remember that silent letter!

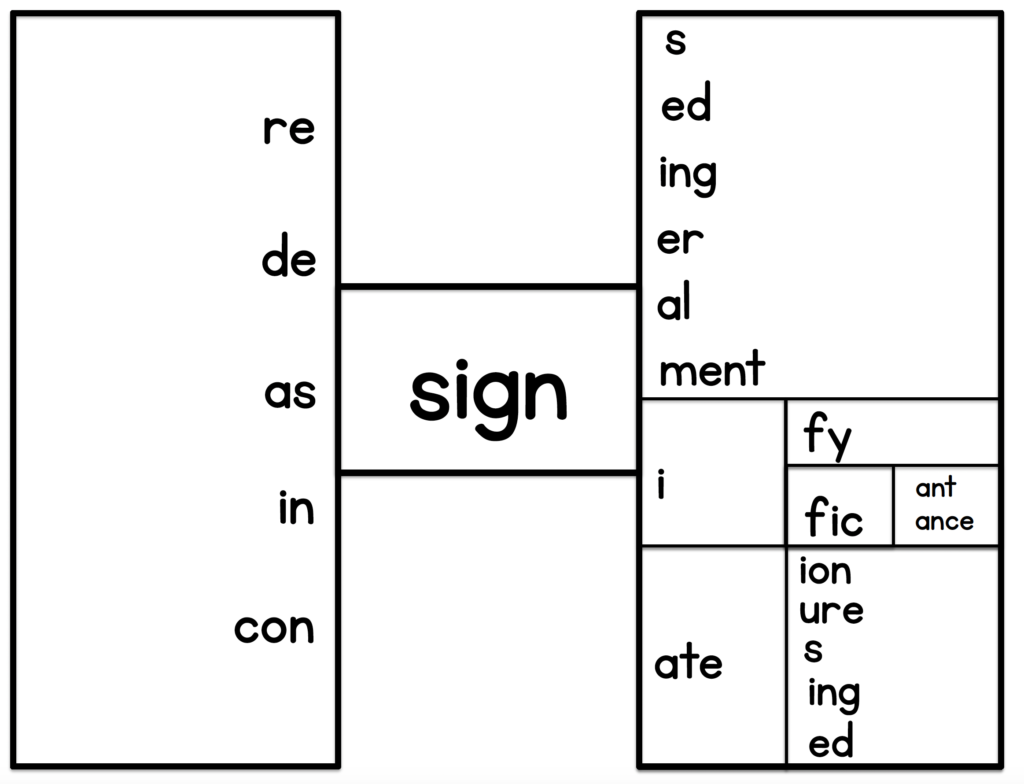

Another example of this is with the word “sign”. We do not hear the <g> in “sign” but we do hear it in related words “signal”, “signature”, and “significant”. These words all share a root. According to etymonline.com, “sign” comes from Latin’s “signare” (where I’m assuming the <g> was pronounced). This is a great time to create a word matrix for your students like the one shown below. (Note that depending on the age you teach, you can include fewer prefixes or suffixes and still show lots of word relatives!)

Click here to download a digital version of this matrix.

Click here to see a video explaining this matrix.

Putting It All Together (Practicing All of the Silent Letters):

As I mentioned, I do not teach these all at the same time.

- I teach <wr> after silent e because most of the single-syllable words with <wr> have short vowels or silent e words. I want to wait until there are enough words they can read and spell.

- I recently moved <kn> to after vowel teams because when I taught it any earlier, there were not very many words to choose from!

- I teach <gn> much later after Unit 6 where all syllable types have been introduced units because there are not that many single-syllable words with gn.

- I must admit that I have not been consistent with mb! I used to teach it with <gn>, but then I realized I could teach it right after closed syllables because most of the single-syllable words with mb are closed syllables. I find that you don’t have to spend a lot of time on <mb> because they sort of adjust easily to that sone since it’s tricky to make that final /b/ sound anyway. I think it’s more about awareness and acknowledgment that there is this silent letter!

After you’ve taught all of them, you can spend a day reviewing by sorting words by sound: /n/, /r/, and /m/. Write words on note cards and use those sounds as headers. Read the words and sort them into the correct category.

Encourage students to be curious about words they encounter outside of the classroom. Encourage them to look for silent letters in books, signs, and any other printed text.

Resources

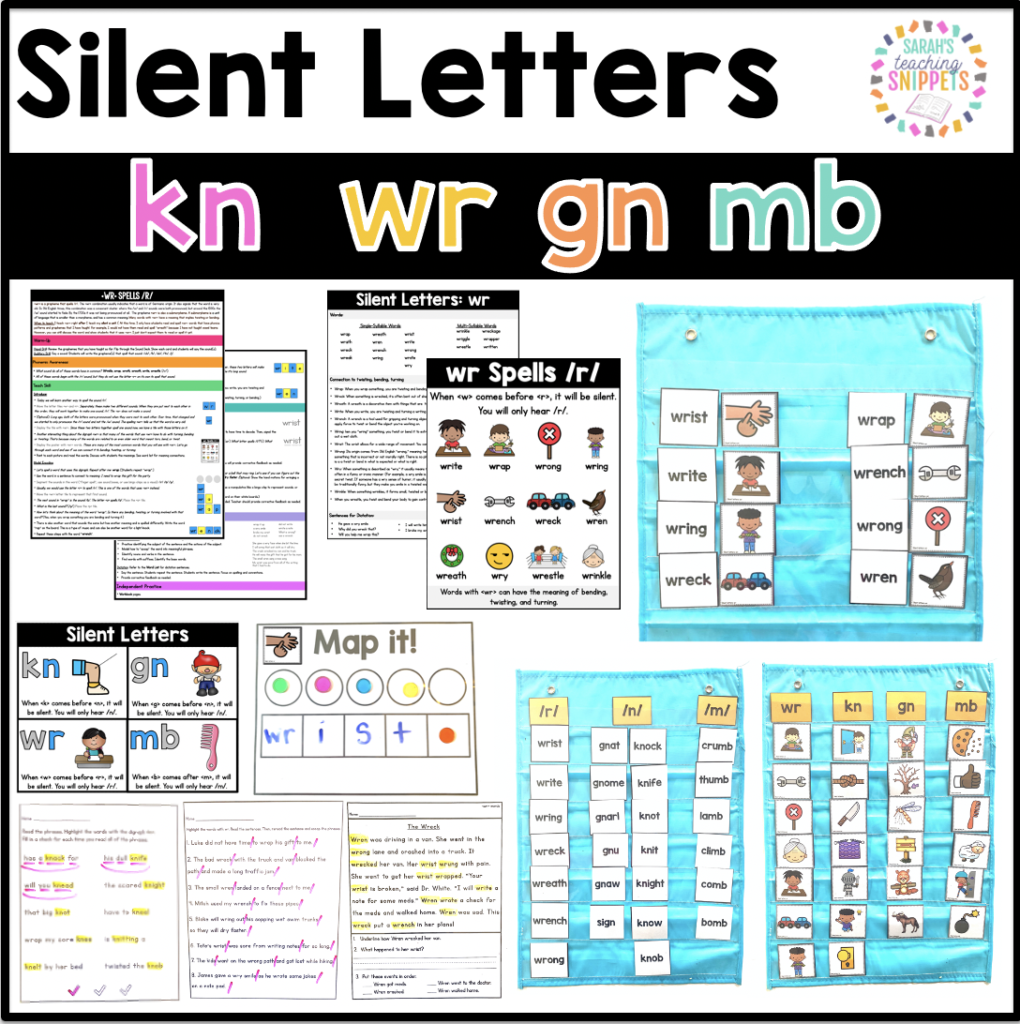

If you’re looking for resources to teach these silent letter combinations, you may want to check out this:

You can find this silent letters resource here.