What is Orthographic Mapping?

Have you ever wondered how students memorize sight words or why some students seem to effortlessly learn new words while others can’t seem to make them stick? This post is all about a theory called orthographic mapping, which was originally introduced by Linnea Ehri. More recently David Kilpatrick has written books about the topic that caught my interest and transformed my teaching. Orthographic mapping is the process of creating sound-symbol connections to recall the spelling, pronunciation, and the meaning of words.

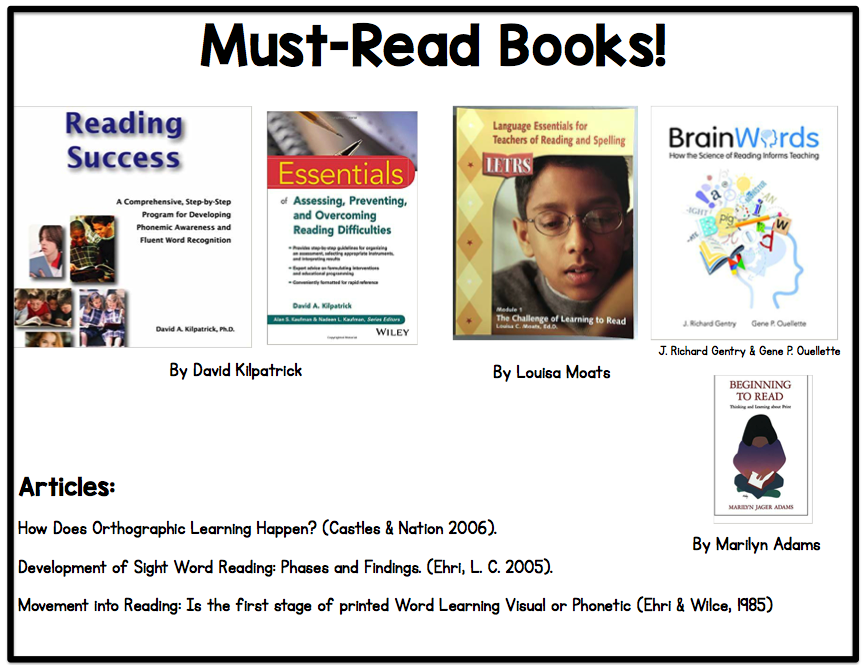

This post uses information from a few different resources, which I will list at the bottom of the post. I highly recommend reading these books when you get a chance. This is just an overview, and I’m hoping that it inspires you all to dig deeper with those books.

(Disclaimer: I do not claim to be an expert. I’m just super interested in all of this and have been studying and attempting to apply this information as best I can. This post is my attempt to summarize and break it down in a way that makes sense to me. It’s just as much for you as it is for me! I have a really hard time remembering things, so creating a post like this helps me to wrap my brain around it and hopefully remember it! Ha! I hope it can do the same for some of you.)

What Does Reading Require?

I should start with the big picture: Reading requires two skill sets: Printed Word Recognition and Language Comprehension.

This post is focusing on printed word recognition. Word recognition requires phoneme awareness (sound awareness) and phonics (alphabet awareness- which symbols link to those sounds).

This post will go into how new readers take unknown printed words and turn them into known “sight words” or words automatically recognized.

But First… What’s happening in the Brain

Research says the brain reads by breaking words into sounds. Our brains are naturally wired for speech, but not for reading! (Louisa Moats) Reading is a human invention developed over thousands of years.

- (To read about the evolution and history of reading, check out Maryanne Wolf’s book called Proust the Squid).

Our brain relies on other systems already in place mostly in the brain’s language center to work together to read. There are four systems working together when we read:

- One part of the brain (orthographic processor) identifies and processes the letters and letter patterns that our eyes see on the page. It’s what helps us remember letter sequences for spelling.

- Another part of the brain (phonological processor) identifies, remembers, interprets and produces speech sounds. Phoneme awareness is just one of the jobs of the phonological processor.

- A third part connects the word to meaning (meaning processor). When we read, the orthographic processor and phonological processor must communicate with the meaning processor to make sense of the words we are reading. Another word for this is the semantic processor.

- A fourth deals with background information and sentence context (context processor). The context processor interprets words.I find this one super interesting because it mainly supports the meaning processor. As you know, context helps us determine a word’s meaning by using the words around it. Although context is helpful with self correcting, but it is not effective alone word identification.

- (This information is from Louisa Moats: LETRS and Marilyn Adams: Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning about Print)

The phonological and orthographic processors work together for word recognition. Automatic word recognition (identifying a word “on sight”) happens after the word is read and mapped over and over and neural connections have gotten stronger and stronger. For some kids, this happens quickly after only a few repetitions, while with others, it takes seemingly endless (possibly hundreds of) exposures. (See my post on dyslexia.)

After students have mastered many words (meaning they have stored those letters patterns in their own mental lexicon), then they can begin to read using these familiar patterns. They may be quicker to read “p-an” and “m-an” because they have read “can” so many times and have “mapped” the letters a-n to the pronunciation “an”.

I always tell my kindergarten students that reading begins with our ears. This is so true, but I didn’t how true it was for a long time. They always get a kick out of this because of course they think reading begins with their eyes, looking at print. Reminding myself of this has really shaped how I teach reading and spelling. Read on to learn more!

Orthographic Mapping: How words become “sight words”

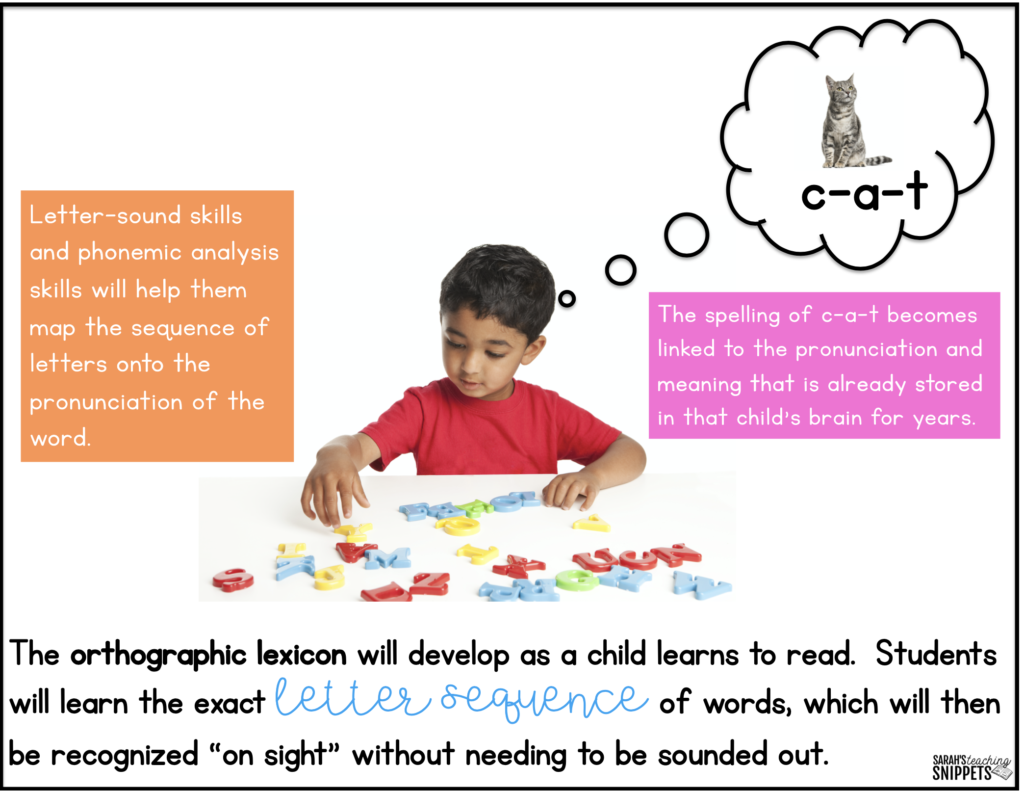

When students are first learning to read, they are sounding out most words. As they read more, they start to recognize words “on sight” without having to decode. But how does this happen? They need to store these letter sequences correctly (for word recognition) through orthographic mapping.

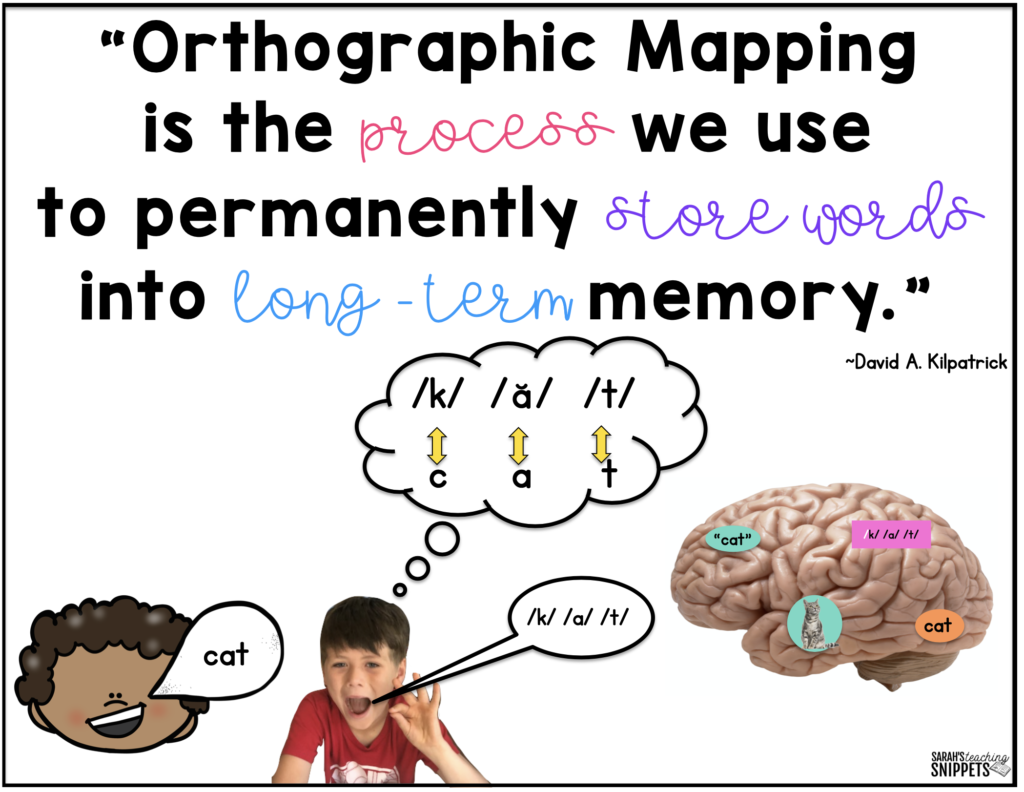

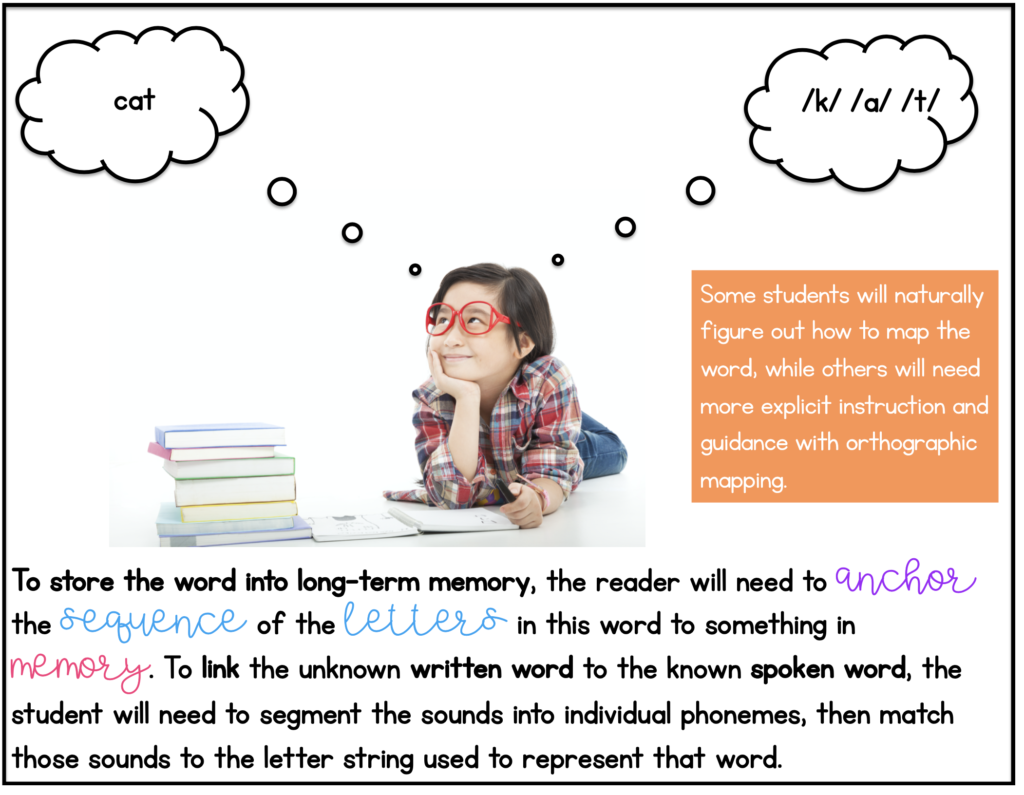

Orthographic Mapping is the process we use to store words into long term memory. (David Kilpatrick) These stored words are words that are recognized instantly without decoding. Skilled readers may develop orthographic mapping skills naturally, while others need more explicit instruction, guidance, and repetition to do so.

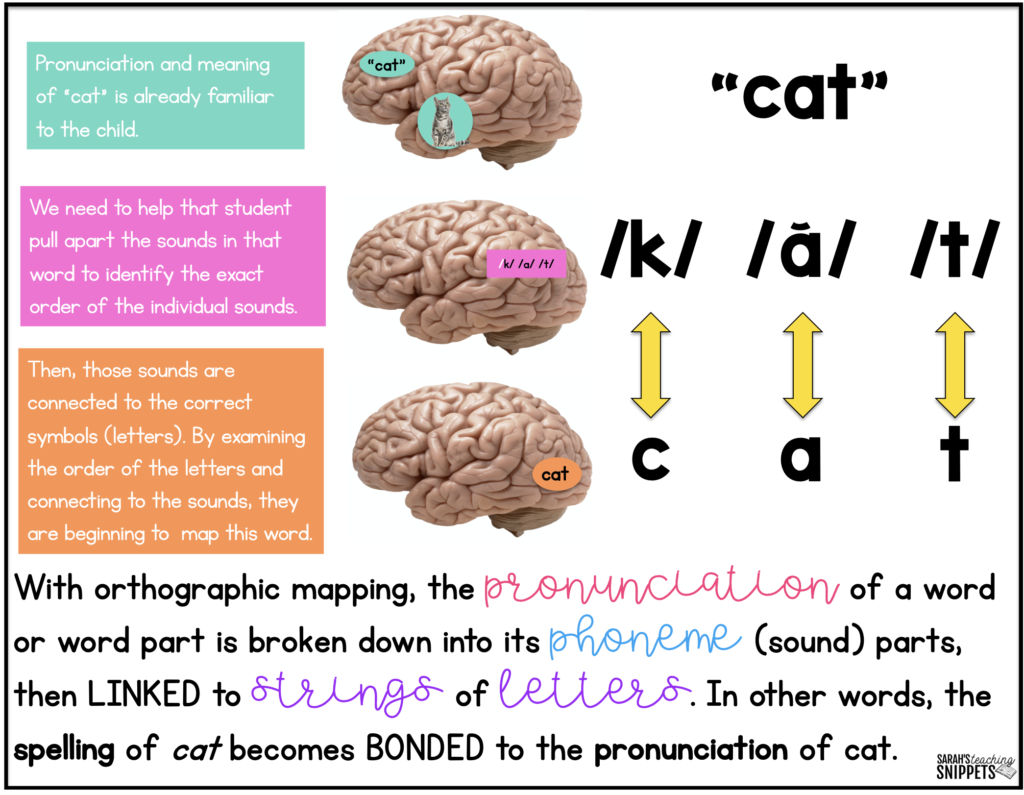

In his books Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties and Equipped for Reading Success, David Kilpatrick explains that with orthographic mapping, a reader is using the oral pronunciation of words that is already stored in memory with the correct letter (orthographic) sequences. He goes on to say the sequence of letters are anchored to the pronunciation of words. These pronunciations are already stored in our long term memory because we learn to speak well before we learn to read. I tried to break it down as I understand it here:

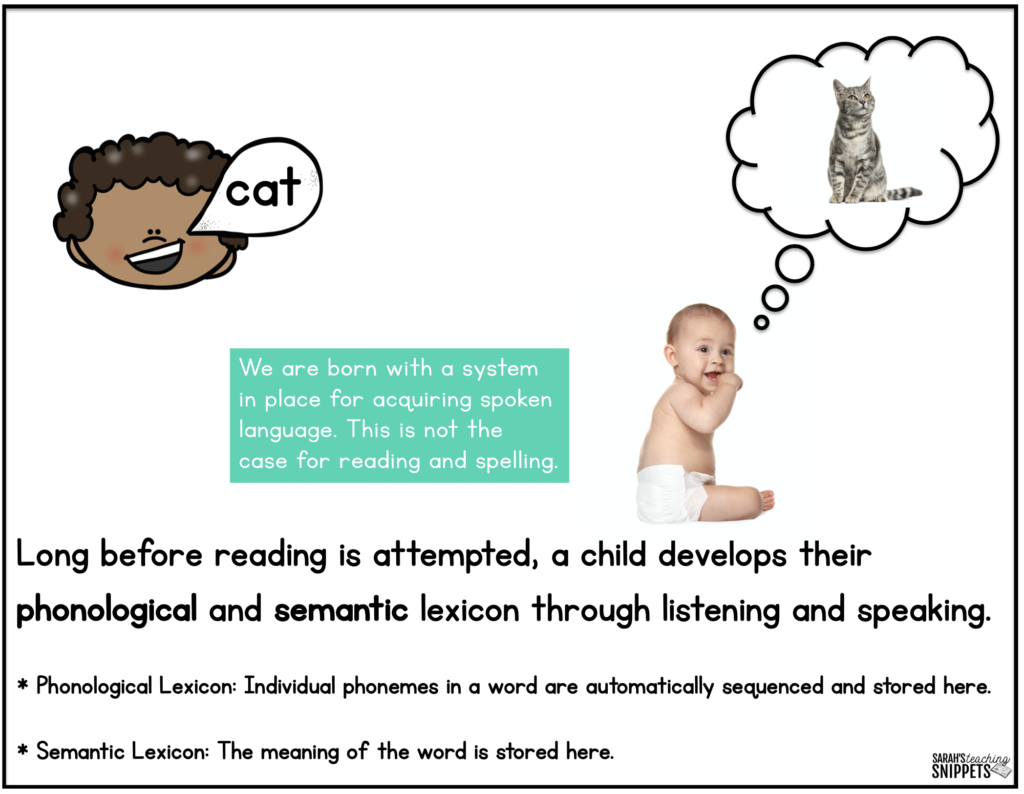

Developing a Phonological Lexicon

When toddlers learn to speak, each individual phoneme (sound) of a word is sequenced automatically, then stored in the brain’s phonological lexicon. Basically, that word is in that child’s word bank.

They can tell the difference between a cat and a hat, even though they only differ by one sound.

They recognize and interpret the sounds in those words and connect it to meaning (a furry animal or a thing you put on your head).

The phonological lexicon also includes word parts! (This will be relevant later in my post.) Once a child is ready to read, it’s time to develop the orthographic lexicon.

Let’s look at how this orthographic lexicon is developed.

Turning Unknown words into Sight Words

Remember that reading is a man-made skill and there is not a specific part of the brain that is designed solely for reading. Our brains use other systems in place together to make it all happen. It really is quite amazing!

The first few steps explain how phonic decoding works:

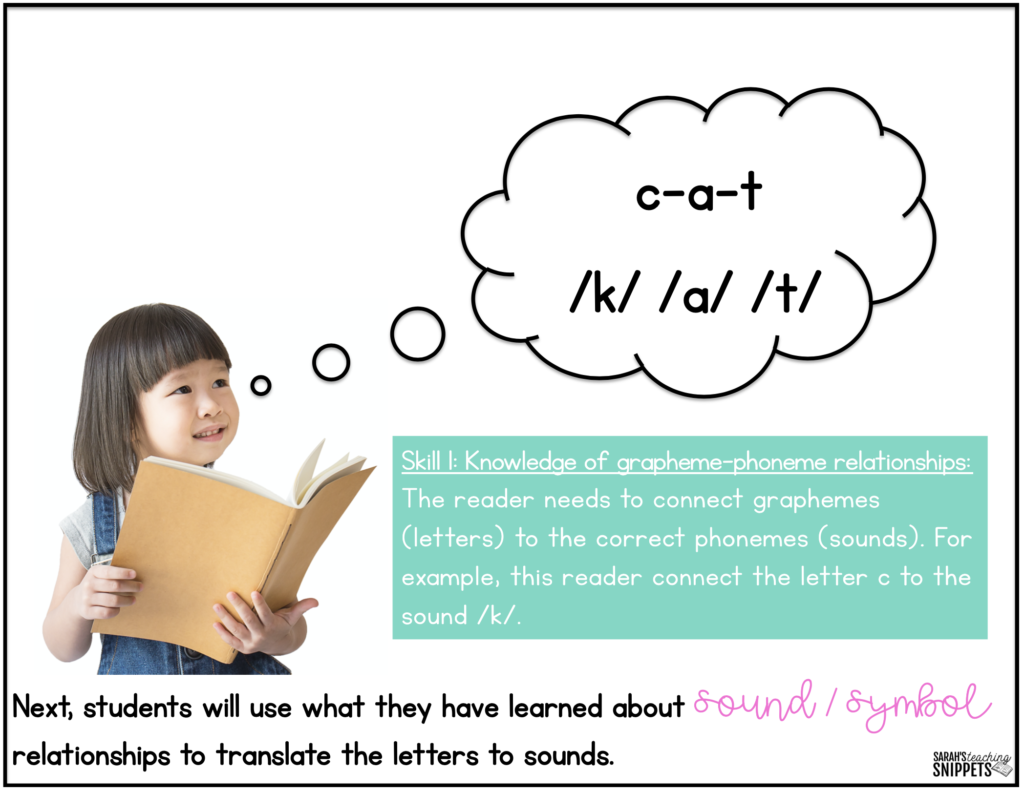

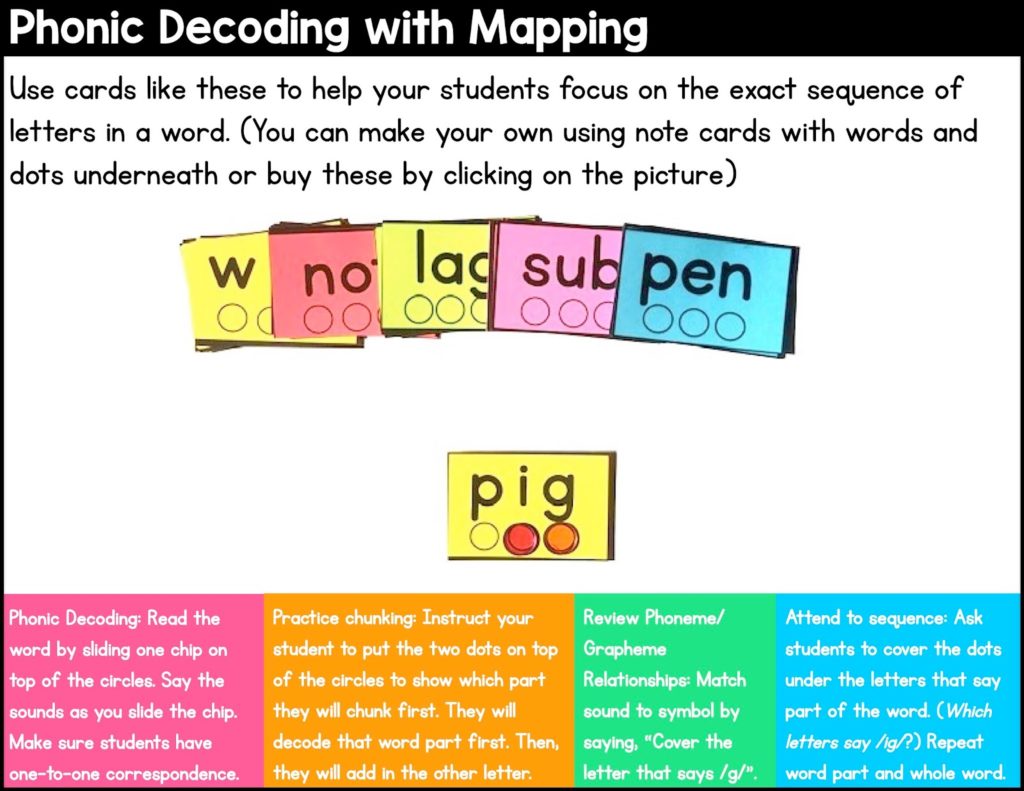

The following slide demonstrates how decoding (phonics) works. Keep in mind, this is only one piece of the puzzle. Keep reading to see what piece of the puzzle leads to word recognition!

Although phonic decoding is an essential skill for reading, it alone may not lead to future word recognition (knowing the word by sight) for all of our students. This is where orthographic mapping comes in! Think of it as going backward from phonic decoding.

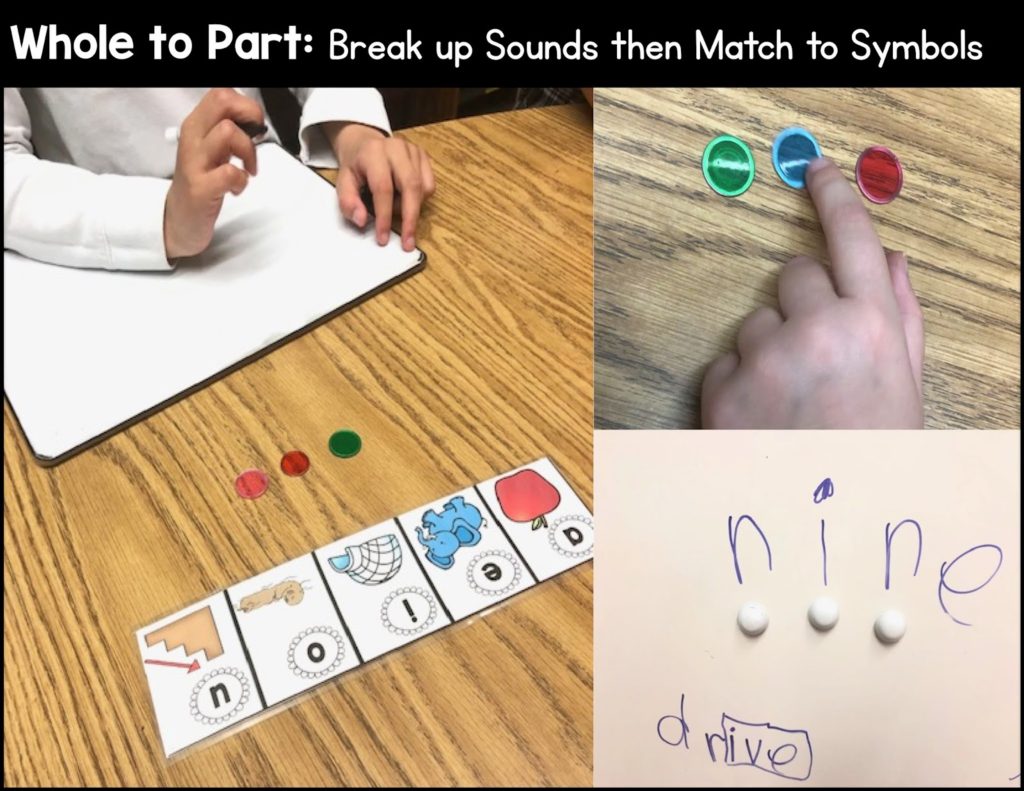

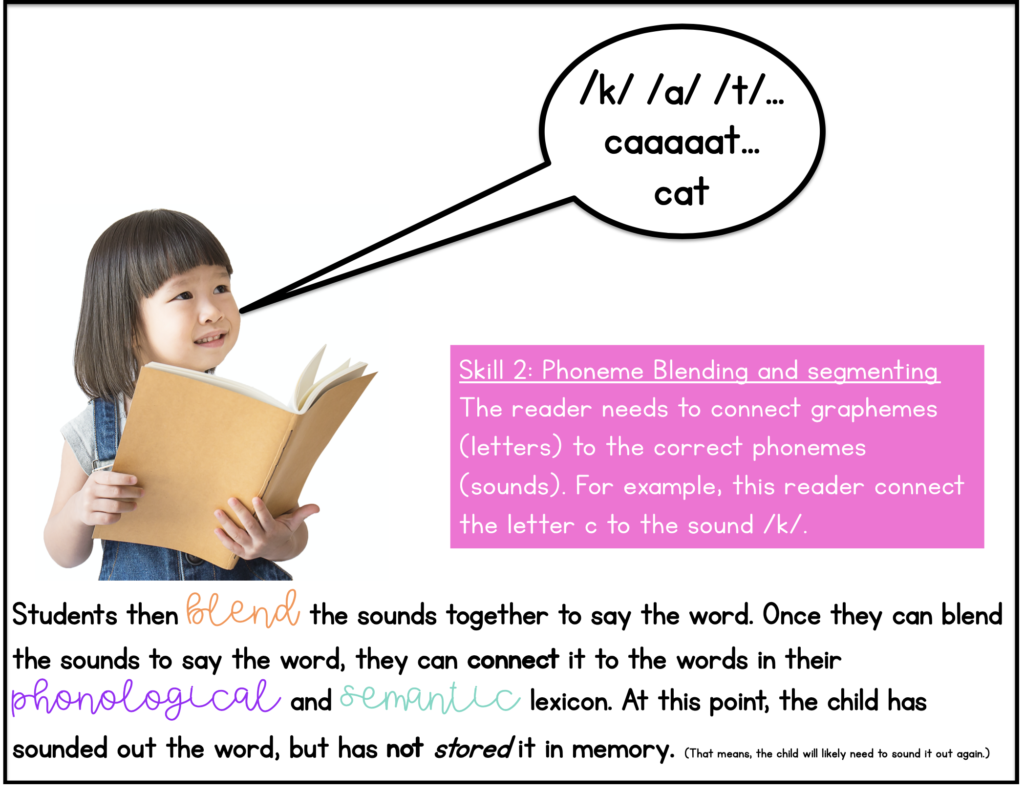

- With phonic decoding, students are taking the individual sounds (that they have translated from the letters) and blending them to make a whole word. (Part to whole.)

- With orthographic mapping, students will take a whole word and break it into its sound parts and connect to the correct graphemes (letters or letter combinations), paying special attention to the exact sequence of letters and how it connects to the sounds. (Whole to parts.) It’s this process that helps get the word stored in long-term memory.

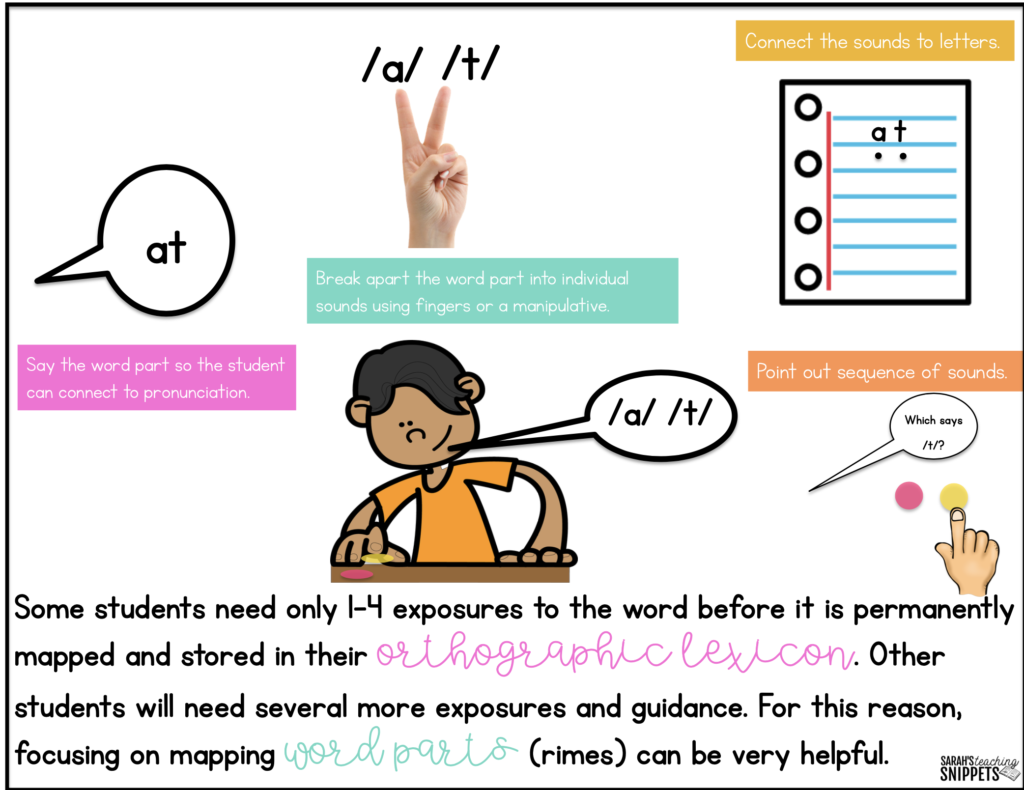

Remember above when I said that our phonological lexicon also involves word parts? That’s good news for our struggling readers because they can map common word parts and apply them to new words. Here is an illustration of how it’s done:

Common Reading Practices to Reconsider

Using Context and other Strategies to “Read” Words

I was trained on guided reading and balanced literacy with an emphasis on reading strategies, mastering “sight words”, and the belief that simply exposing kids to literacy (no matter how implicitly) would lead to successful and strategic readers. Except after a few years I realized that this worked for many of my readers (likely the ones that would learn to read in spite of their teacher or the instruction). However, this wasn’t enough for some of my students.

I realized that the strategies (without explicit word study instruction) were actually just helping them compensate and cover up the fact that they couldn’t decode. This was leading to constant guessing.

Turns out that contextual guessing not only doesn’t help our struggling reader store the unknown word in memory, but it actually hinders them from learning the word. If they can guess, then they are not actually attending to the sequence of letters in the word. (Archer& Bryant 2001; Landi 2007)

Without strong foundational skills, these students were left to guess and use context. This is not enough. I couldn’t figure out why they weren’t applying certain rules that I “went over” during shared reading or for a few minutes during word work. Remember above when I talked about the phonological and orthographic processors that are in charge of word identification? These processors are linked to the context processor through the meaning processor. So that means word recognition does not happen through context.

Context does help once a word has been decoded. If a new reader decodes an unfamiliar word and doesn’t get the stress right or gets one sound wrong, often then the context can help the student self correct that word. But context alone should not be the main tool in our students’ reading tool belts.

Using Leveled Readers

So here’s where I’m really going out onto a limb and I may ruffle some feathers. I no longer use leveled books and the traditional guided reading method with my beginning readers. Eek! I said it! Hear me out though. Think about those beginning leveled readers (levels A-D). What are your kids mainly doing? They are using the picture, looking at the first letter and guessing. Context plays a big part, too. There are few if any opportunities for students to actually apply phonic decoding skills with words they can actually be successful with. This goes against all of the research on how we learn to read.

That isn’t to say that there isn’t a place for leveled books later. I do use them once my students have a stronger foundation. In kindergarten, I would only use those leveled readers for those kids who can map more effortlessly. You know who they are. They are the ones who can learn sight words easily and who decode quickly. They are the exception though. I would still not use those alone, even with those kids. I want to make sure those kids who can seemingly read, have a strong foundation too. I would still spend a lot of time on phonics and morphology skills. I would also check their spelling skills! (See this post about spelling instruction.)

With the average kindergartener, I would not rush those sight word flash cards or the leveled readers. I would spend more time giving them opportunities to apply their newfound phonics skills in context using controlled texts. More about that below under Implications for Teaching. I do think there is a time and place for guided reading. I just think if we rush it too soon before foundational skills are in place and before they have had time to map words and word parts, we are setting some of our readers up for failure or for bad reading habits.

The Sight Word Myth

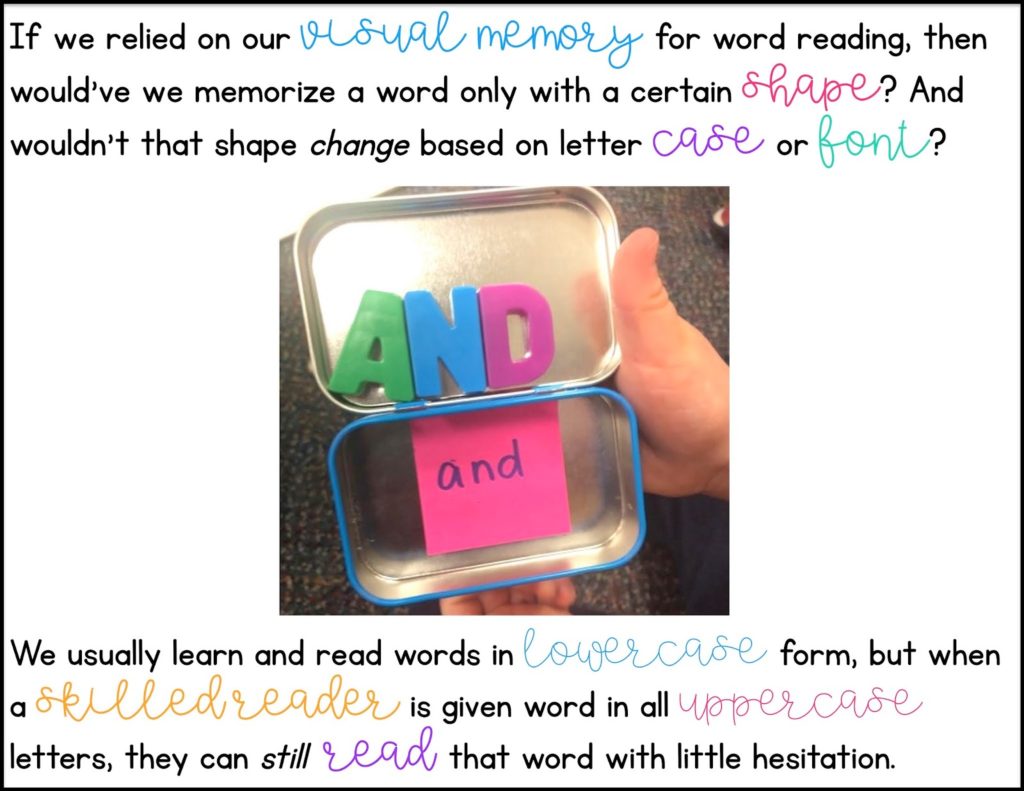

When I began teaching, I was taught (or maybe I inferred based on the methods I was taught) that good readers simply see a whole word and memorize it. Give ’em a set of flashcards and have at it. This is based on the assumption that we memorize words using our visual memory. Turns out, when we see a word, the input is visual but we do not store them visually.

Written words are actually stored (for later recall and recognition) on many levels at the same time: Phonologically (pronunciation), orthographically (spelling), and semantically (meaning). According to David Kilpatrick (and other researchers), there is actually a small correlation between sight word vocabulary and visual memory (although it does help with letter identification). There IS a strong correlation between sight vocabulary and phonemic awareness. As I explained above, to store a word permanently, students need to use phonemic awareness and letter knowledge to “map” that word’s orthography (spelling).

If that’s all too much to take in now, just think about this:

The whole language theory rests on this idea of using visual memory to store words. For years, I assigned sight words without any teaching behind them. I didn’t think I was practicing whole language techniques, but actually, I was just by doing this. For years, I guided my kids to rely on context and other strategies that did not require them to really dissect the word. These strategies are fine to use as long as strong foundational skills about our language are explicitly taught. I was sort of missing that last part though. 😉 And a big reason I didn’t dedicate more time to phonics and morphology is because I believed that English didn’t make sense (and quite frankly I didn’t know anything about it!) That’s the second myth– that sight words are mostly irregular and don’t make any sense. More about that in this post about English orthography.)

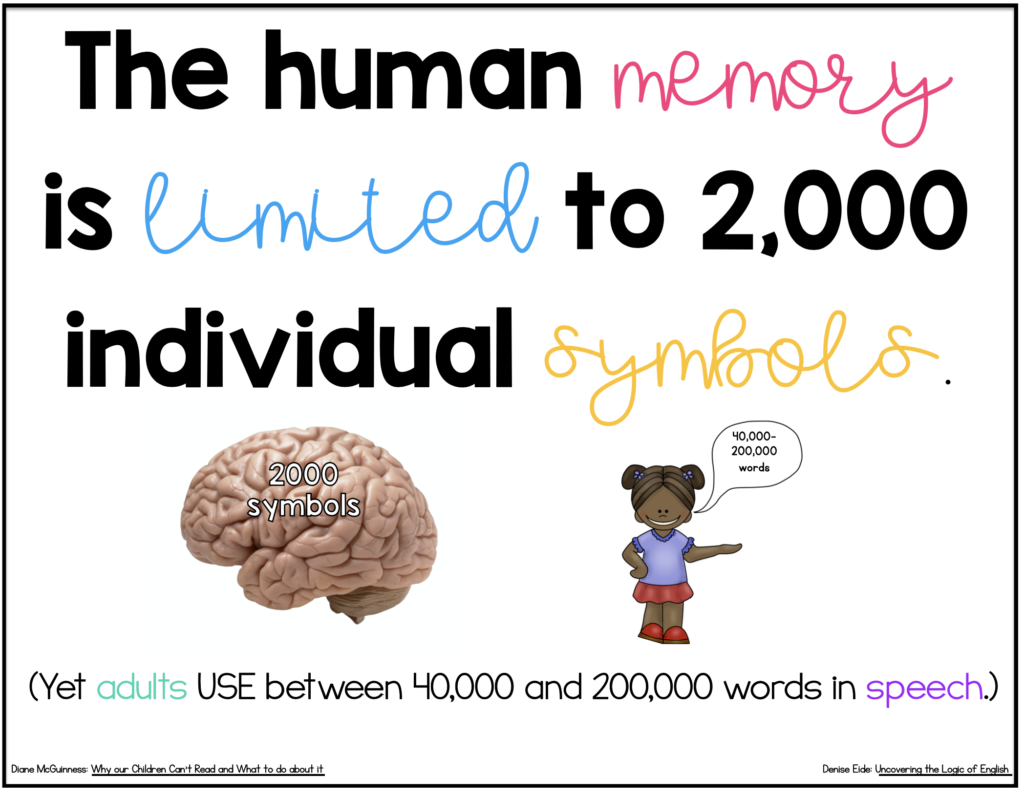

One more thing that I thought was really interesting is that the average human memory can only actually hold 2000 individual symbols (Diane McGuinness: Why our Children Can’t Read and What to do about it), yet the average adult knows 40-60,000 words (and a well-educated adults knows 200,000). (Denise Eide: Uncovering the Logic or English) That’s quite the discrepancy between how many words our oral language uses vs. how many words our brain can memorize.

This is a big hole in the whole-language/memorize-sight-words-without -phonics approach. I cringe when I think about how I “coached” my students to just see it and say it when I showed them a “sight word”. I actually told them not to sound it out! AGH! I was under the impression that they had seen this word enough time and it should just be popping into their head. But guess what Sarah from the past… if it didn’t pop out of their mouths, then it wasn’t properly mapped in their memory. What I was doing was encouraging them to guess the first thing that looked like that word.

Now I know that with guidance, my students can and should “sound out” these high-frequency words instead of guessing. Now I know what you’re thinking. Many kids do seem to just memorize those sight words pretty effortlessly. That’s true enough, but they are still using the same process of mapping word parts and words, just faster. I think of those kids as the kids that will learn to read in spite of teaching methods or proper instruction. There are definitely those kids. But what about the 20% or more that don’t?

The science tells us that skilled readers (like you) read words on a page effortlessly because you are “matching the words with spelling images that have been mapped or stored in your brain”…”Your reading circuitry is in place.”. (Brain Words How the Science of Reading Informs Teaching by J. Richard Gentry and Gene P. Ouellette) Our brain has a lot of work to do to get to that point though. We need to listen to the science of reading and apply it to our teaching practice.

How To Teach High-Frequency “Sight” Words?

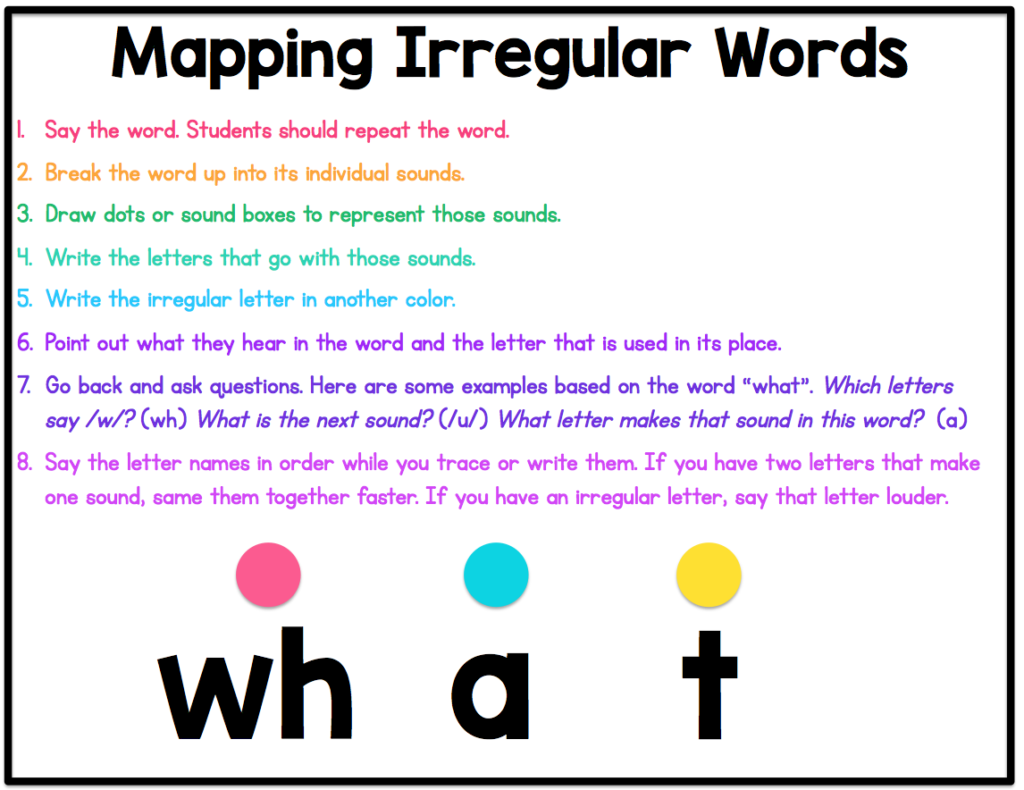

We map them the same way we would any other word. If it is “irregular”, we point the irregular part(s) out and still map it. There are a few high frequency words that really don’t make sense (could is one I still can’t figure out), but most are either off by one sound or they can be explained by a “generalization” or morphological connection. (Read more here)

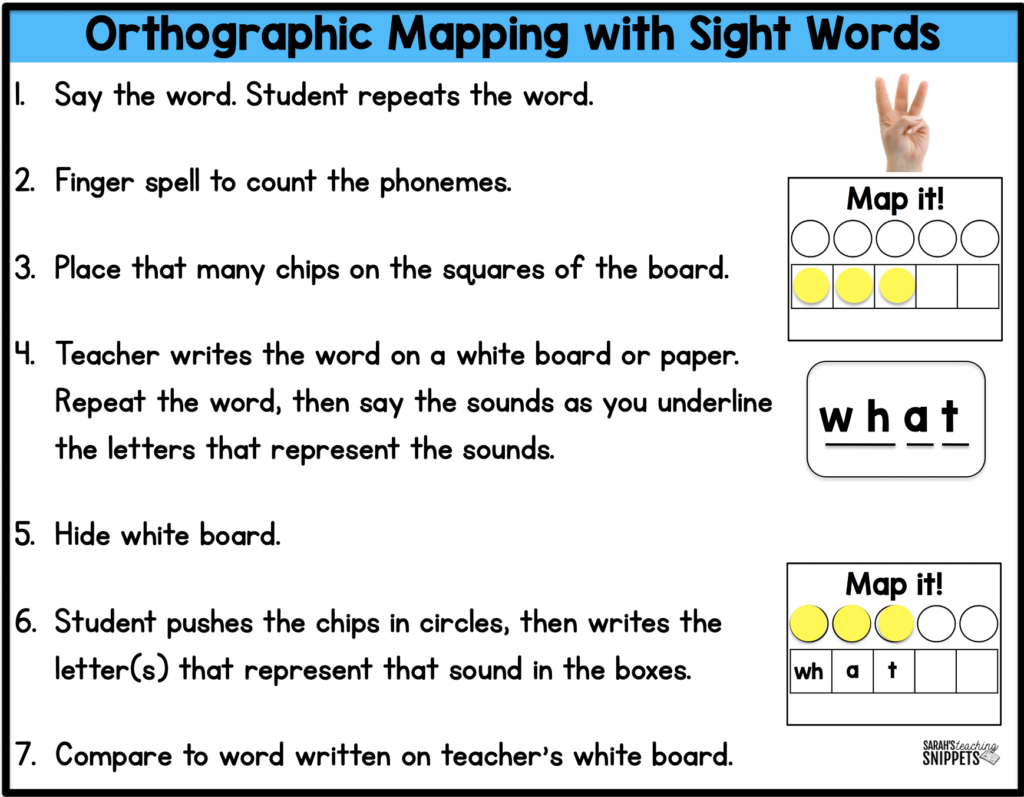

Here is another visual that you can download.

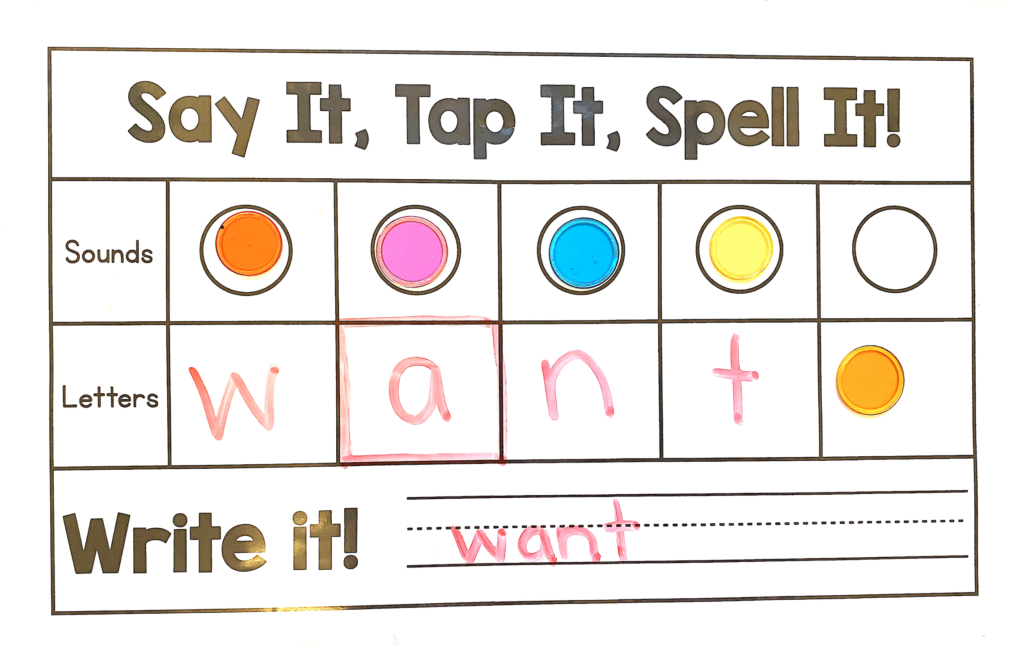

Here’s another example with the word “want”.

Implications for Teaching

All of the technical and scientific stuff here is interesting and relevant to understanding how our students learn to read and, perhaps more importantly, why some kids struggle so much. So now, it’s our job as teachers to take this information that has been given to us by these amazing researchers and apply it to our teaching practices in the classroom.

I explain below a few ways that I’ve done that, but one thing I want you to walk away with is spelling. I know a trend is to throw spelling out the window. Heck, I even believed in that trend for a while. Here’s what you should throw out the window: (1) Spelling lists that are random. (2) Spelling tests that just promote memorization. (3) Spelling lists that put too many spelling patterns at once.

As you will see below, spelling should be integrated into your instruction and can be done with your reading instruction. Encoding and decoding go hand and hand. Asking our students to hear a word, think about knowledge of spelling patterns, and then attempt to write that word is actually very helpful and fits in with all of this research. The key is to follow up with the correct spelling, pointing out the correct sound-symbol correspondence using the methods shown below. Hope this helps!

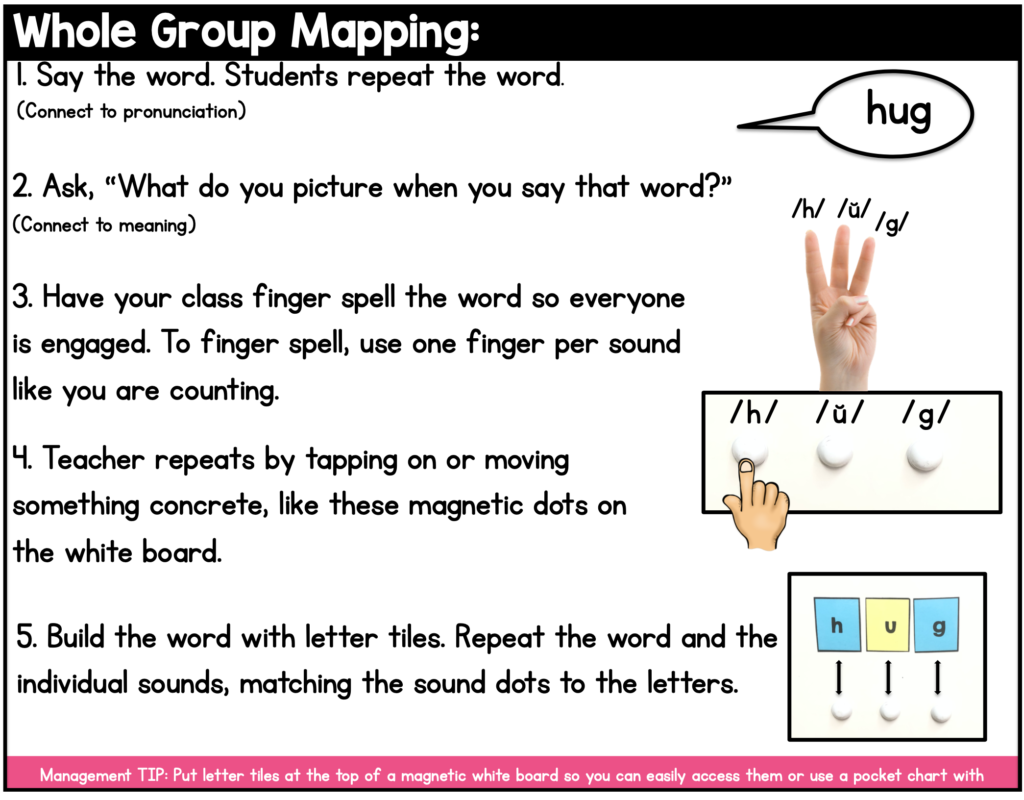

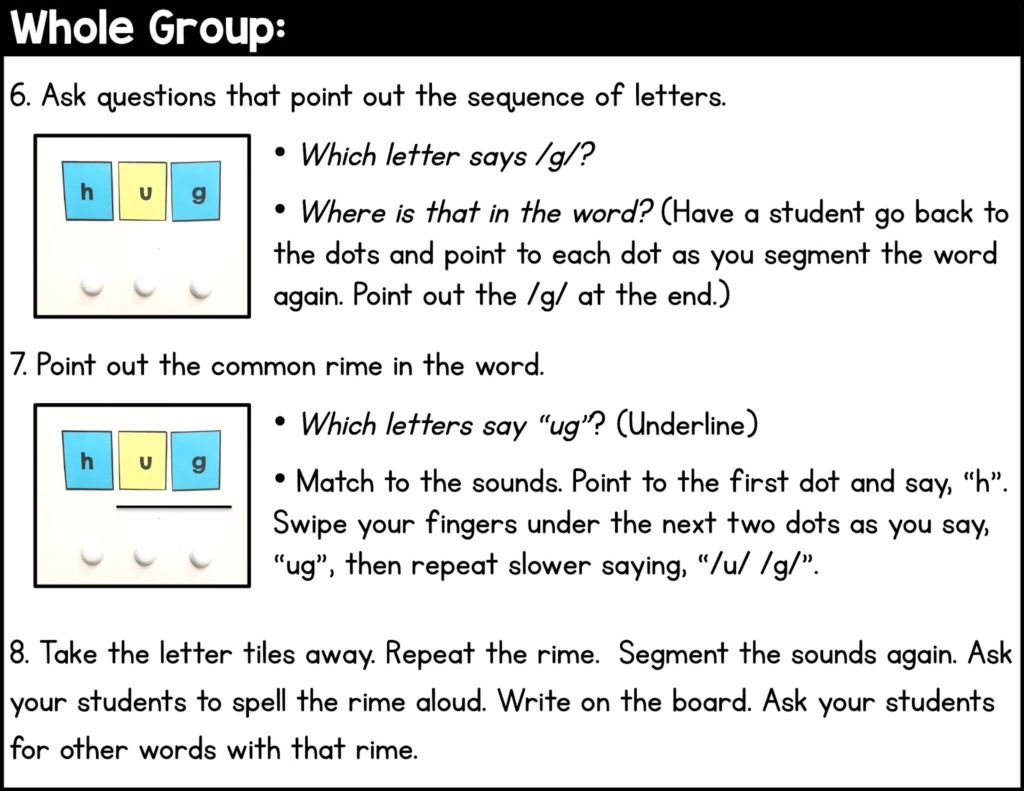

Process for Orthographic Mapping

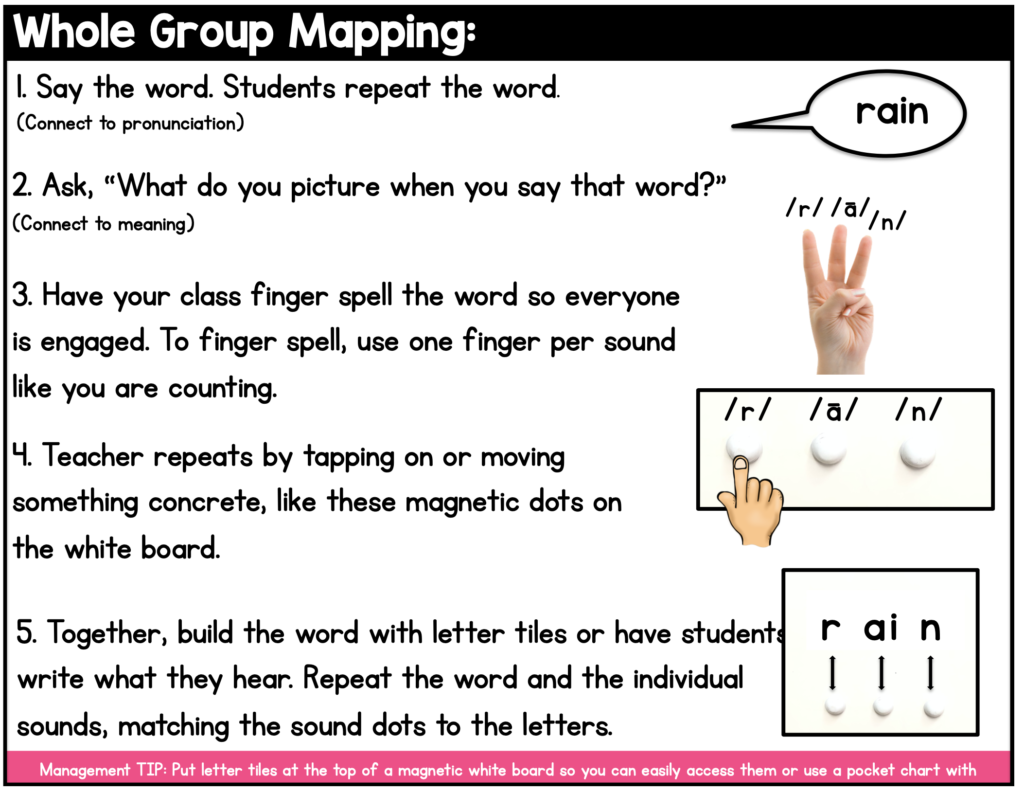

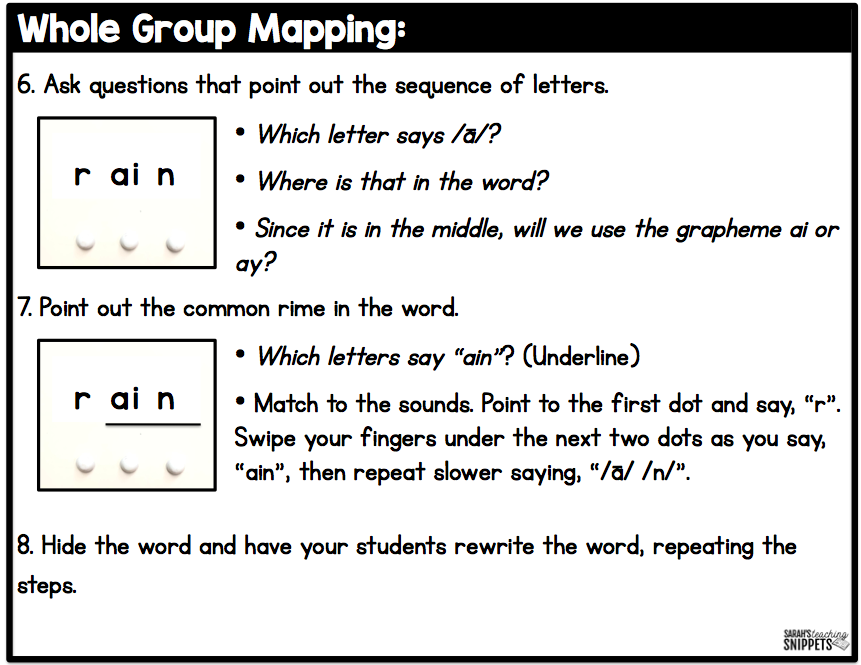

Here is an example that you may do in late 1st grade or early 2nd grade:

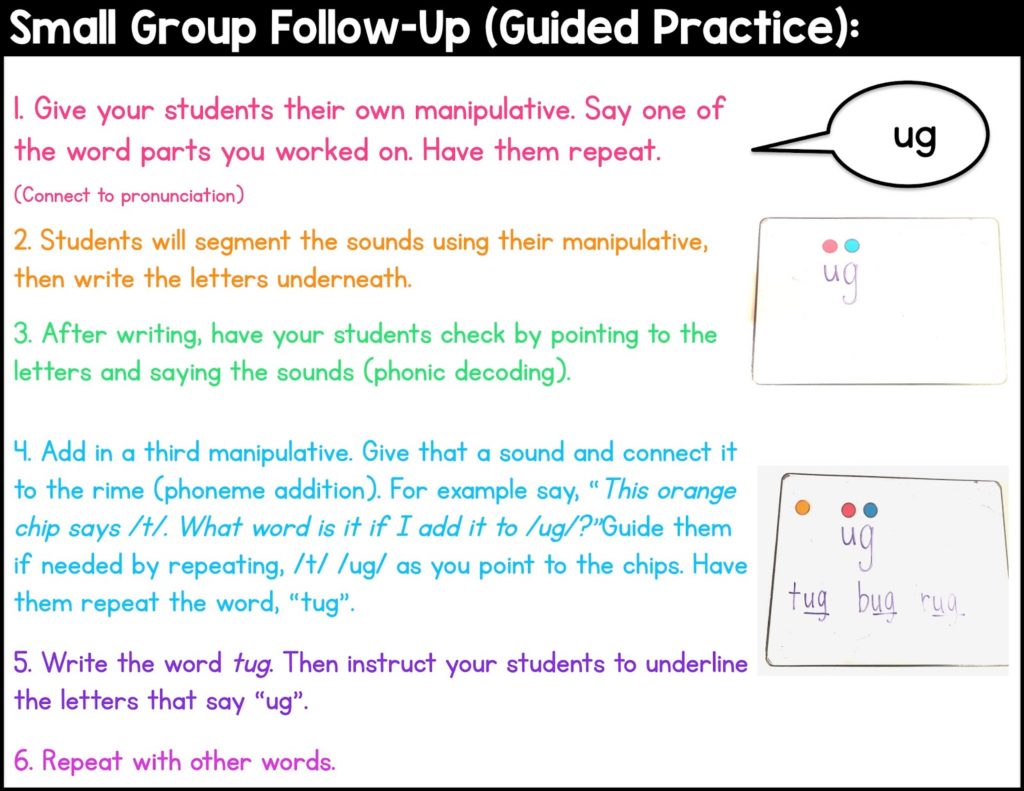

Here is what a small group follow up lesson may look like:

The Role of Phonemic Awareness with Orthographic Mapping

Kilpatrick talks a lot about the importance of advanced phonemic awareness skills with orthographic mapping, like phoneme addition, deletion, and substituting. You will not need to continue this with all of your students. Kilpatrick says that “Typically developing readers will naturally analyze any whole word phonemically and establish an orthographic representation of that word.” However, you will have students who do require this guided practice with advanced phonemic analysis.

Kilpatrick states that weak readers do not naturally engage in orthographic mapping because they lack those advanced phonemic awareness skills.

Below are some pictures from my small group work. We do a lot of phonemic segmenting with bingo chips and, when they are ready, continue with advanced phonemic skills.

- For a kindergartener, I would say “Break up the word map“. They would push the chips as they say /m/ /a/ /p/. Then I would say, “Take away the /m/. What do you have now?” (ap). Then I would slide over a new bingo chip and say, “This is /s/.” I would place it where the /m/ was and ask, “now what is the word?” (sap).

- For first and second graders, it gets a little tricker. You may ask your students to break up sled, then ask them to take away the /l/ and add in /p/. That takes phonological working memory (they are holding those sounds in their head long enough to do something with them) and phonological awareness/analysis.

Kilpatrick recommends doing more advanced phonemic awareness activities as students get older. Admittedly, I was not doing enough of this. I did a ton with kinder and beginning first, but then I focused on phonics and didn’t put time into advanced phonemic awareness. Now that I do put time into it, I really see the value!

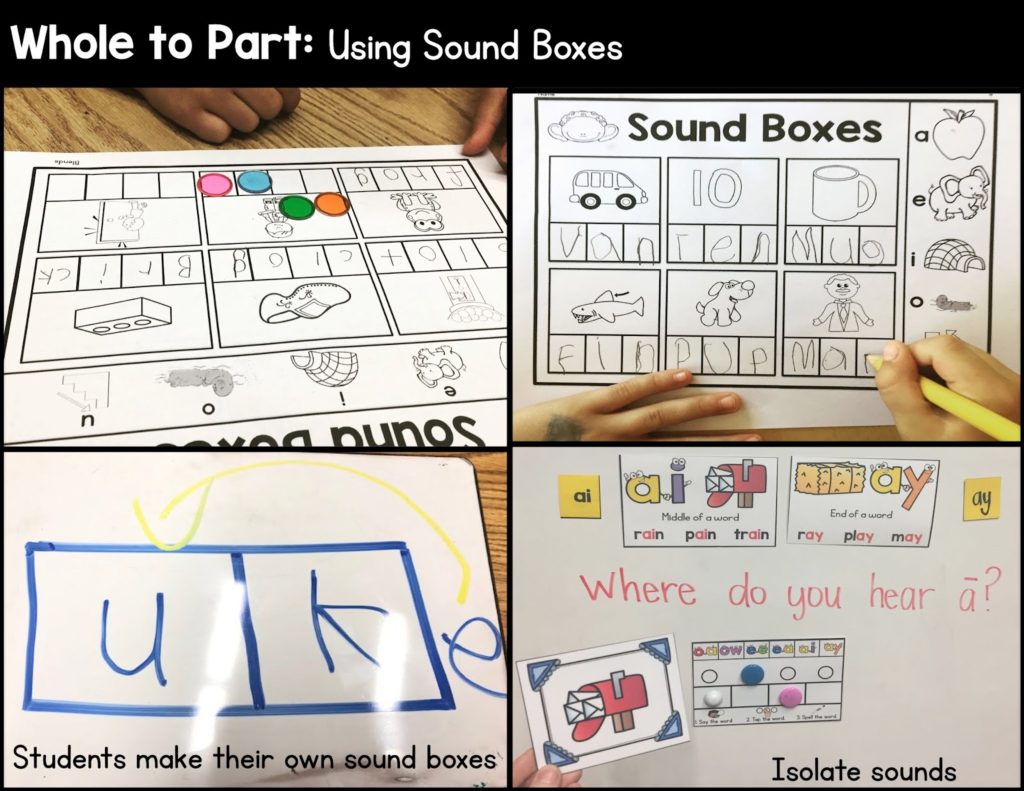

Below is just regular phoneme segmenting and connecting to graphemes. I have a set of sound boxes for several phonetic elements.

You can grab printable Sound Boxes here and digital sound boxes here.

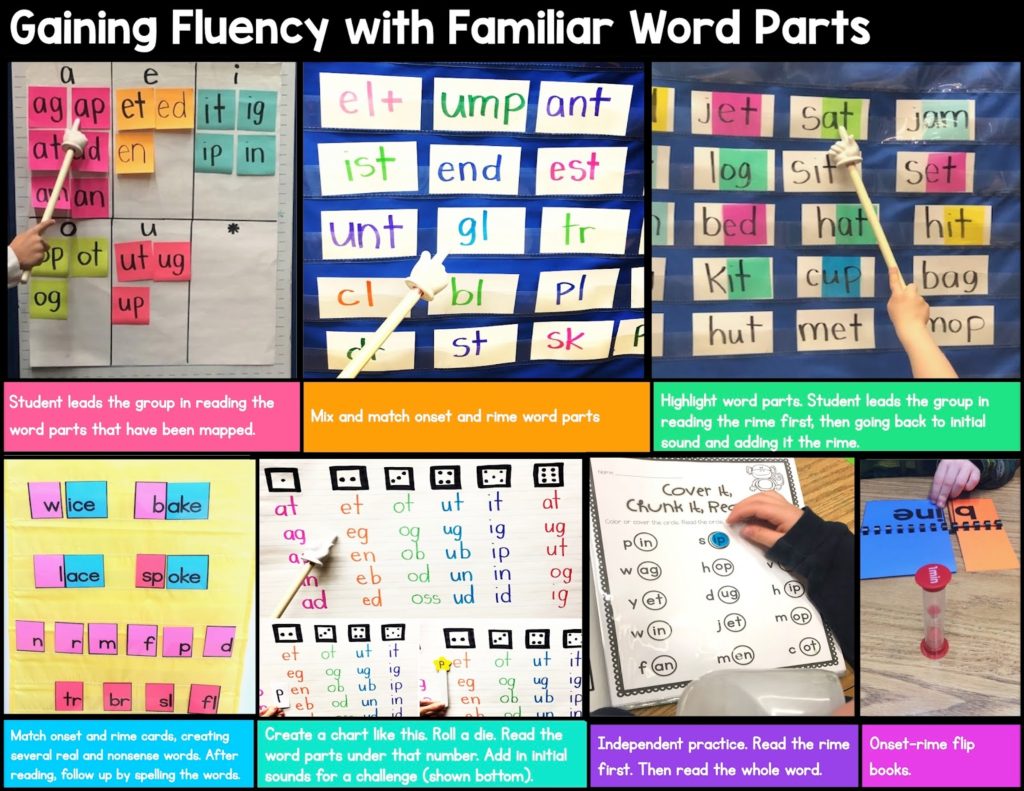

After Mapping: Gaining Automaticity with Word Parts

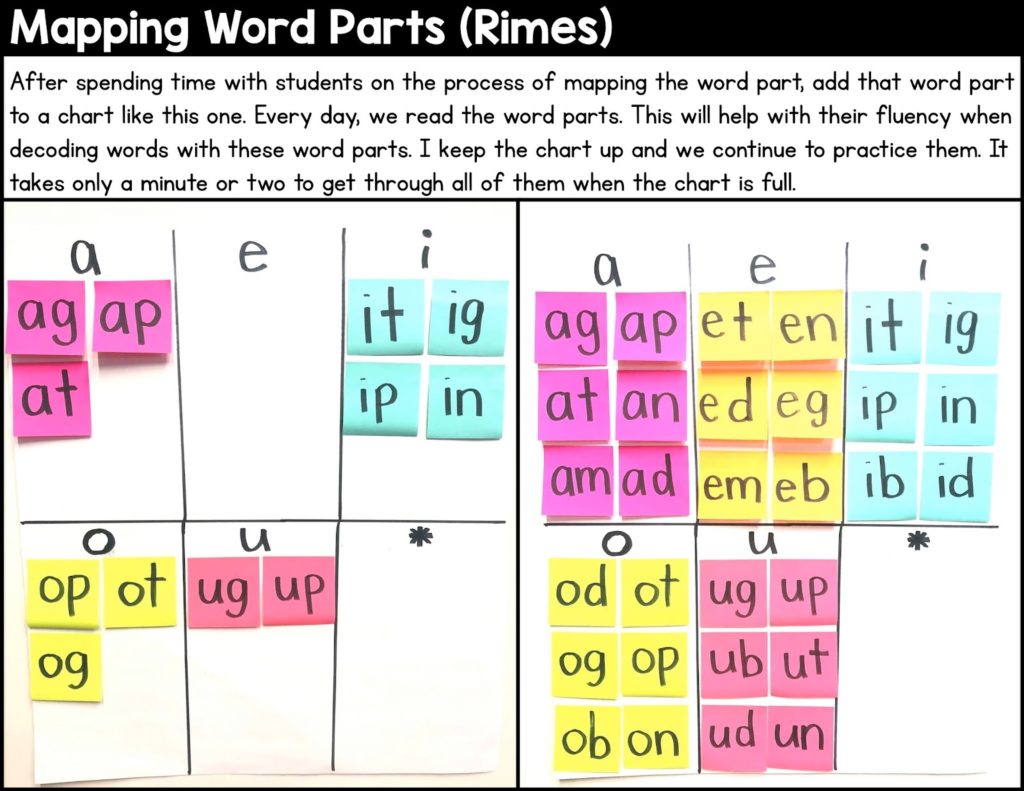

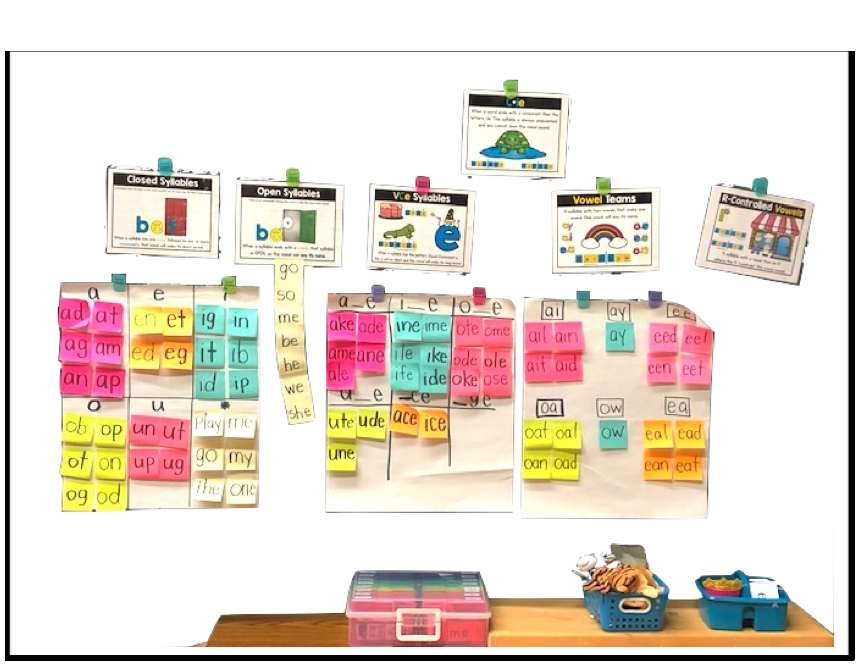

Below is a chart I used after mapping word parts. I had a similar chart for my first and second graders once they learned silent e, vowel teams, r-controlled vowels, etc.

Under that star on the chart above, put irregular words that you have taught. For example, is, has, and was could go there. Map it first for your students, then add it to your chart.

Below shows some charts for silent e and vowel teams.

Here are some activities I’ve done with my students after word parts have been mapped:

I’ve used this activity as a follow-up after we have initially mapped a word:

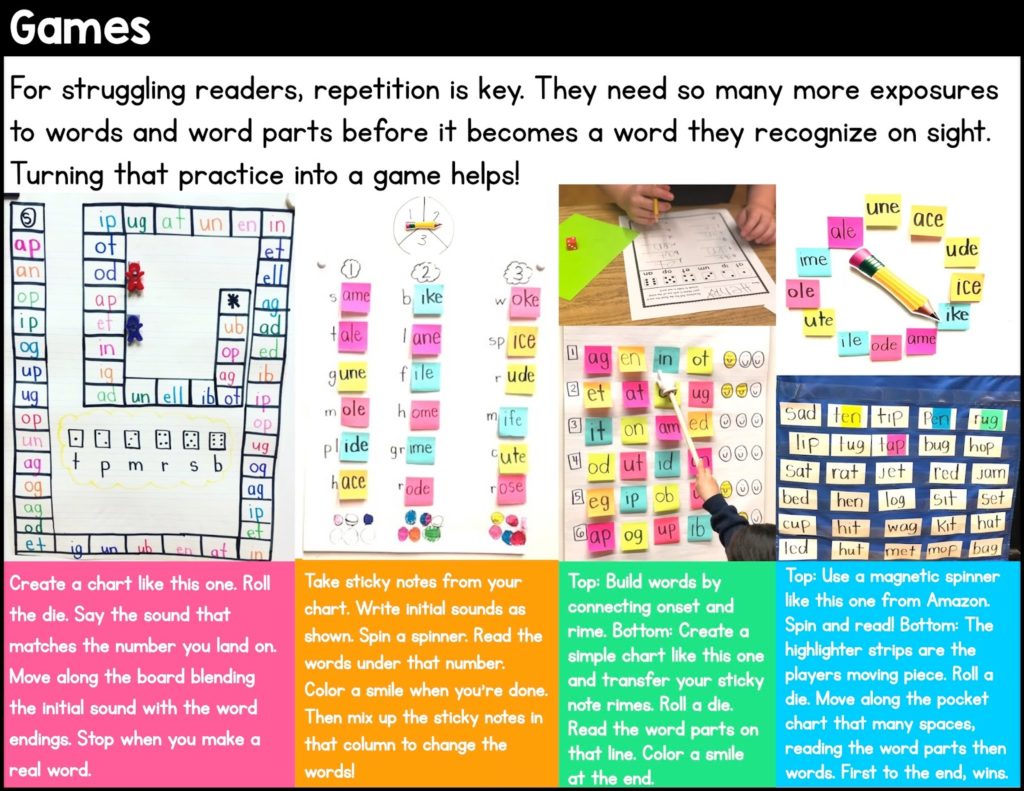

And of course sometimes you just have to mix it up with phonics games! Our students work so hard and often need soooooo much repetition, so making it a game whenever possible is huge!

Click here to download a free template to make a Word Part Race as shown below:

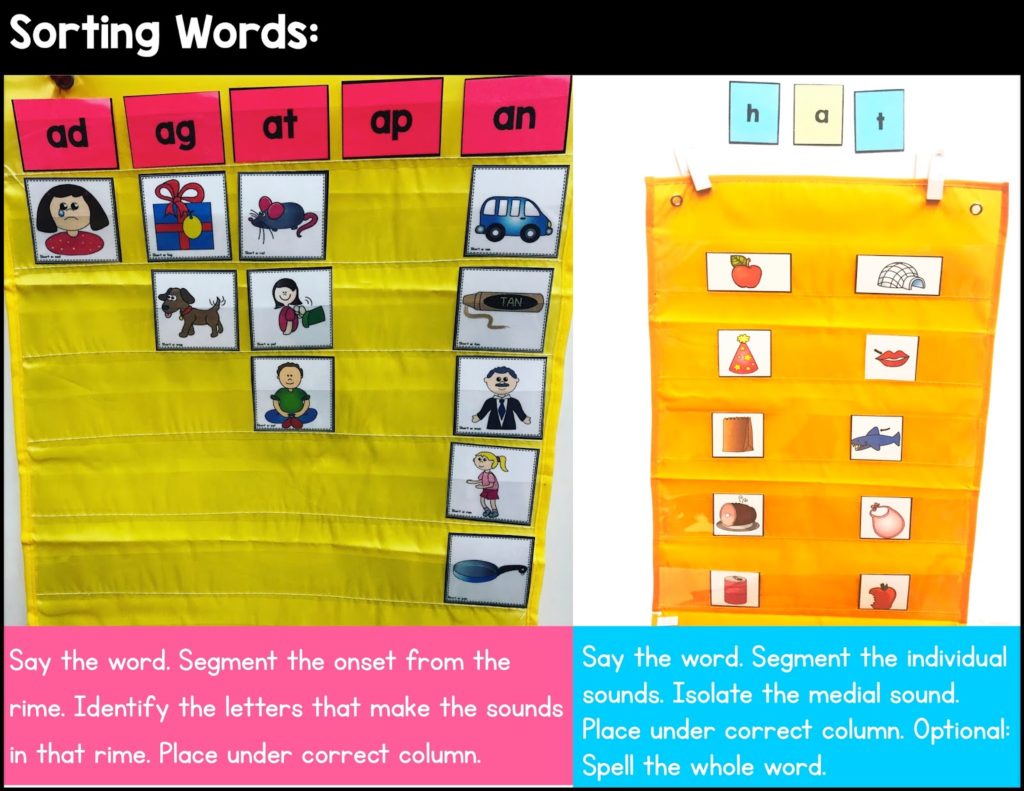

Making your Word Sort Meaningful:

I used to think word sorts were a waste of time because I saw students just looking at the spelling of the word and matching it without reading it. Now I see how valuable they are as long as the right delivery is there. 😉 Below shows a picture of ways that I use sorting that I feel does support orthographic mapping.

Here, they are taking the whole word (the picture card) and they must first use phonemic awareness skills to segment the onset and the rime. Then they have to isolate that rime (for example, “ad”) and match it to the correct letter sequence. This may be easy for some, but let me tell you, it is a challenge for many! That means it’s worth doing!

If you are using word cards instead of picture cards, you just need to make sure they are reading them. If they are doing it as an independent activity, they likely will just try to match without reading. But if you do it as a small group activity, where they are whisper reading the word card and you are guiding, it can be quite effective.

Click here for picture and word cards (Print /laminate and Google Slides).

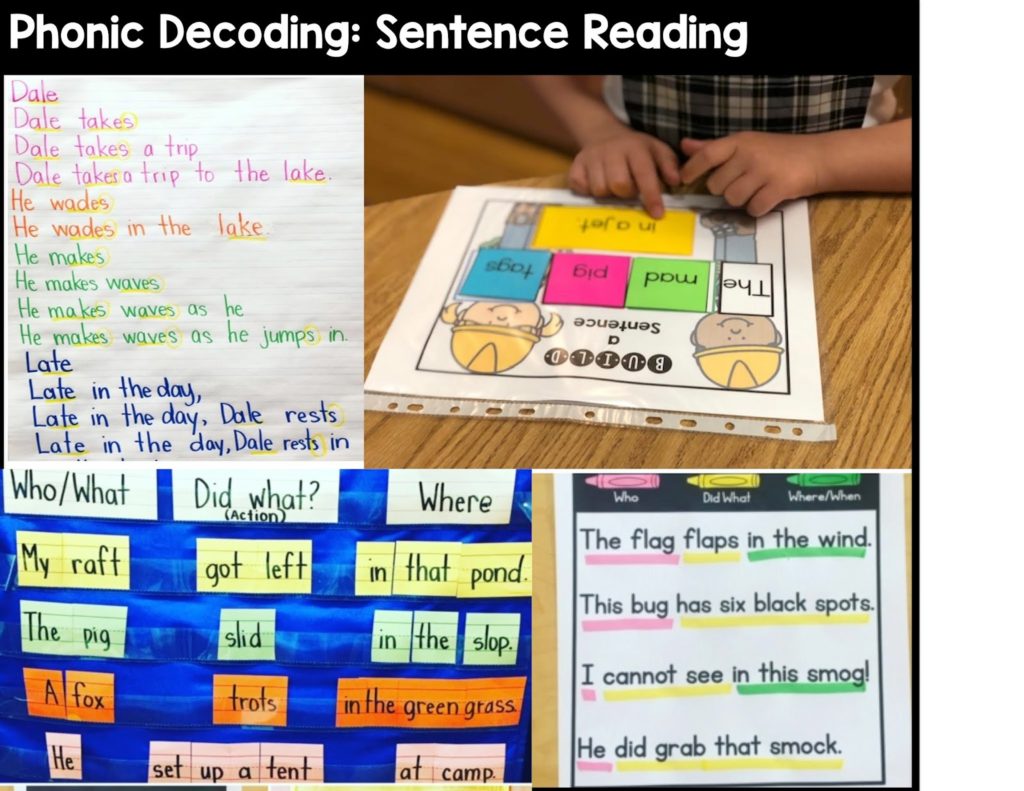

Next Steps: Phonic Decoding with Controlled Texts

After all the mapping, give your students opportunities to practice phonic decoding in context. Here are a few ways I provide controlled decodable texts.

In that first picture (the sentence ladders), I had them identify familiar rimes before reading. This group was working on silent e and we had mapped several word endings (rimes) with silent e.

- First, I had students whisper read word endings that they spotted.

- Then I called on students to share one they found.

- I instruct them to say, “a-l-e, ale”.

- I would underline those word endings as they read them to me.

The other pictures just show normal decoding with sentences, but you can connect by asking, What ending do you see in the word pig? or Which word has the ending et?

Click here for decodable sentence resources.

I also use decodable short stories. You can find some decodable passages (also available as Google Slides) here.

What Skills Are Needed For Orthographic Mapping?

1. Sound-Symbol Awareness: Explicitly teaching and reviewing graphemes (letter or groups of letters that represent a sound) is the first important step.

As I’ve mentioned before, students need to recognize and produce the sound associated with a symbol with automaticity. This begins in kindergarten with the alphabet. (To read a blog post about systematic alphabet instruction, click here. To get resources for systematic alphabet instruction, click here.)

2. Phonemic awareness: I can’t say it enough how important this is. Integrate it into you classroom daily!

Start with rhyming and isolating initial sounds (integrate into alphabet instruction), then move on to stretching words to hear medial sounds and ending sounds.

Next, you can move into phoneme segmenting (breaking words into individual sounds). You can easily do this with the whole class by finger spelling words. You don’t need to wait for students to learn letters before doing this. Students may know one letter or all their letters, but they may (or may not) be equally good at this skill. You can start phonemic awareness activities day 1 in kindergarten!

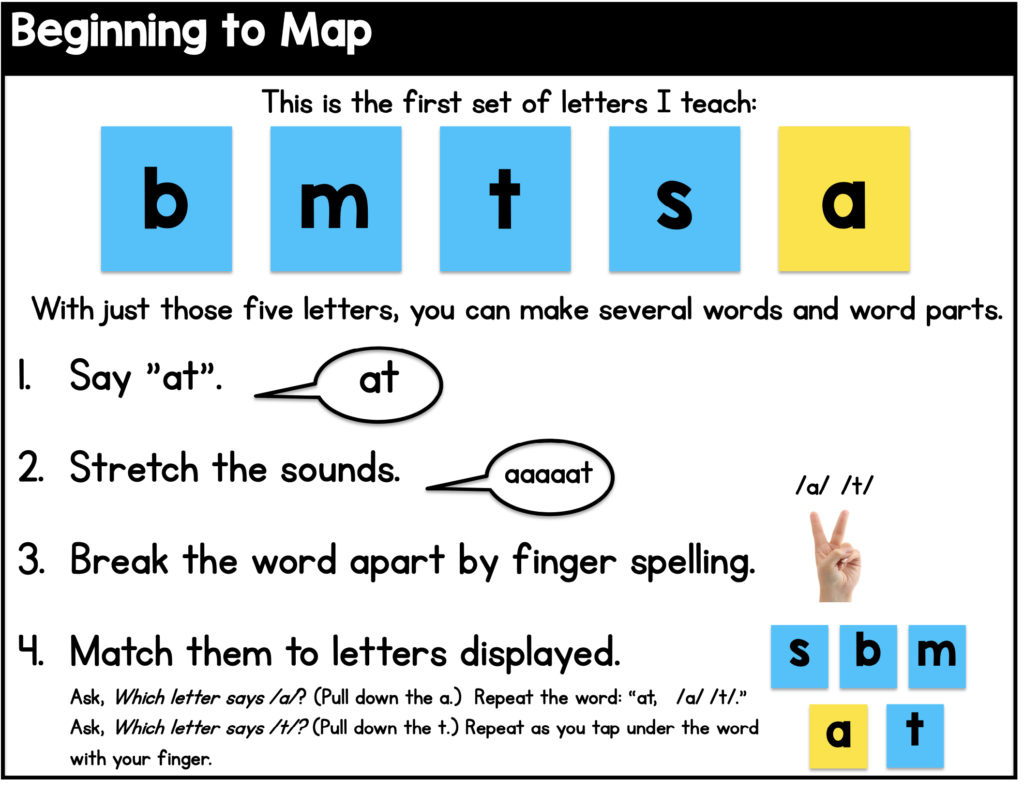

Eventually you merge these two skills and that’s when the magic happens. Since I’ve already been working on phoneme segmenting with finger spelling, they will be ready to start orthographic mapping using word parts or words with familiar letters they have learned. You can even start mapping when your students only know a few letters! Once I’ve taught my first set of letters, I start modeling phoneme segmenting. Some students are not ready to do this one their own, but others are. At this point, I’m modeling these skills.

As you map these word parts, add them to your chart of sticky notes shown above. Then review them daily. This can be done with the whole class, then you can reinforce as needed with small groups. Some kids might be ready to read more words, while others may need more time with each word part. Make a clear sequence to follow to keep you on track.

3. Phonological Long Term Memory: This is that phonological lexicon I was talking about earlier. Interestingly enough, dyslexic students can have a great phonological long-term memory but not have adequate phoneme awareness/analysis skills to effectively map the printed version of these words into long-term memory. You’ll have to read Kirkpatrick’s book to learn more!

Advanced Phonemic Awareness

One thing that I was missing when I originally wrote this blog post was the importance of continuing to do advanced phonemic drills with students beyond first and second grade. Kilpatrick’s book Equipped for Reading Success has a whole section dedicated to drills you can use with. your students. He also provides a free assessment so you know where you need to begin with your students. How does this relate to learning new words? Kilpatrick talks about how typically developing readers may naturally engage in the process of mapping words. However, weaker readers will not naturally engage in this process because they lack the phonemic awareness skills.

References for Orthographic Mapping

The majority of information from this post can be found in David Kilpatrick’s books, which I highly recommend. This blog post is just the tip of the iceberg. Reading his books will give you a deeper understanding and provide a lot more background as well as examples of how to teach.

After reading his book, I went back and read articles and research studies that he recommended. Dr. Louisa Moats has a whole series called ” target=”_blank” aria-label=”undefined (opens in a new tab)” rel=”noreferrer noopener”>LETRS, which I also highly recommend. I went to a presentation of her several years ago and that was a game changer for me. It led me to all of this. Her books are easy to understand and so thorough! This one shown below is the first. If you are pressed for time, simply google her name and read the free articles she’s written.

I also highly recommend Brain Words How the Science of Reading Informs Teaching. So much great information.

Here is research by Linnea Ehri: click here

Related Blog Posts

For more about how to teach reading, click here.

For more about the Science of Reading, click here.

For more about dyslexia, click here.

Resources

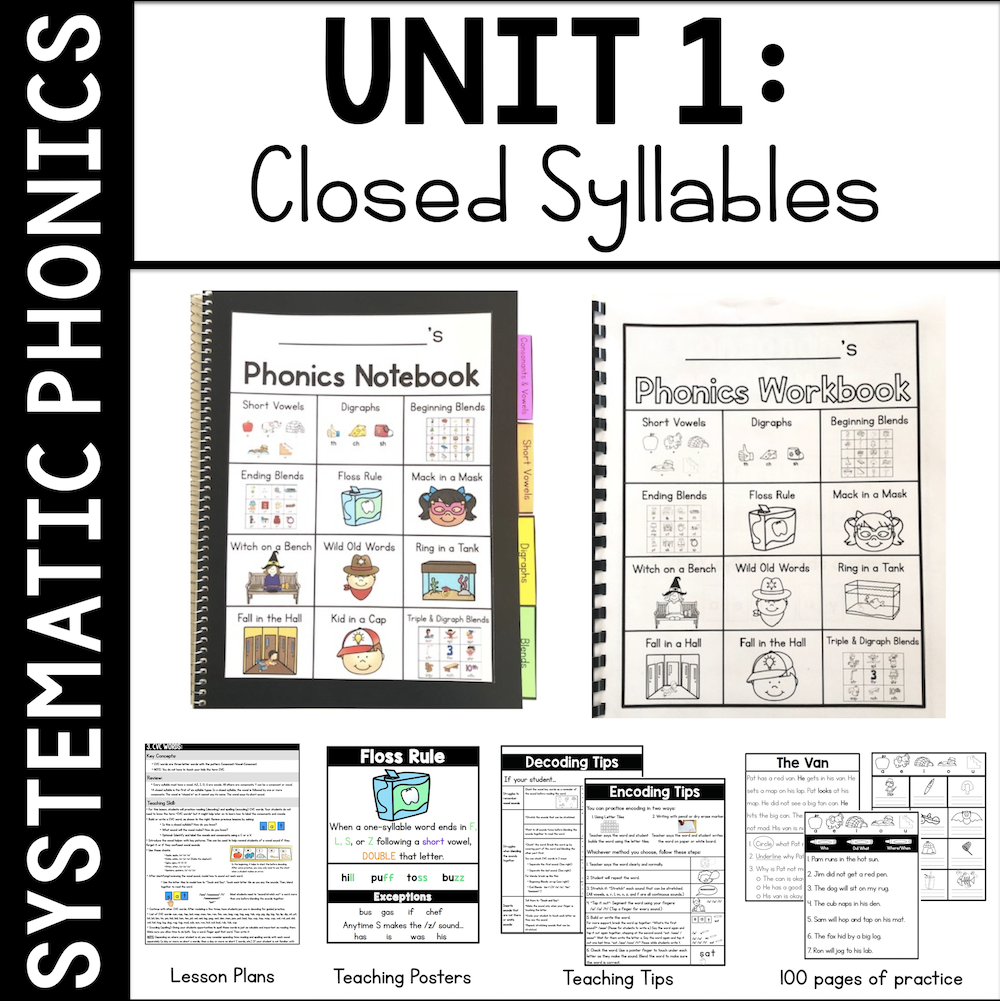

I have tons of resources for phonic decoding and spelling!

If you’re looking for a systematic approach to reading and spelling, click HERE to check out these units.

I also have a few different phonemic awareness resources (printable and hands on). Click here for those.

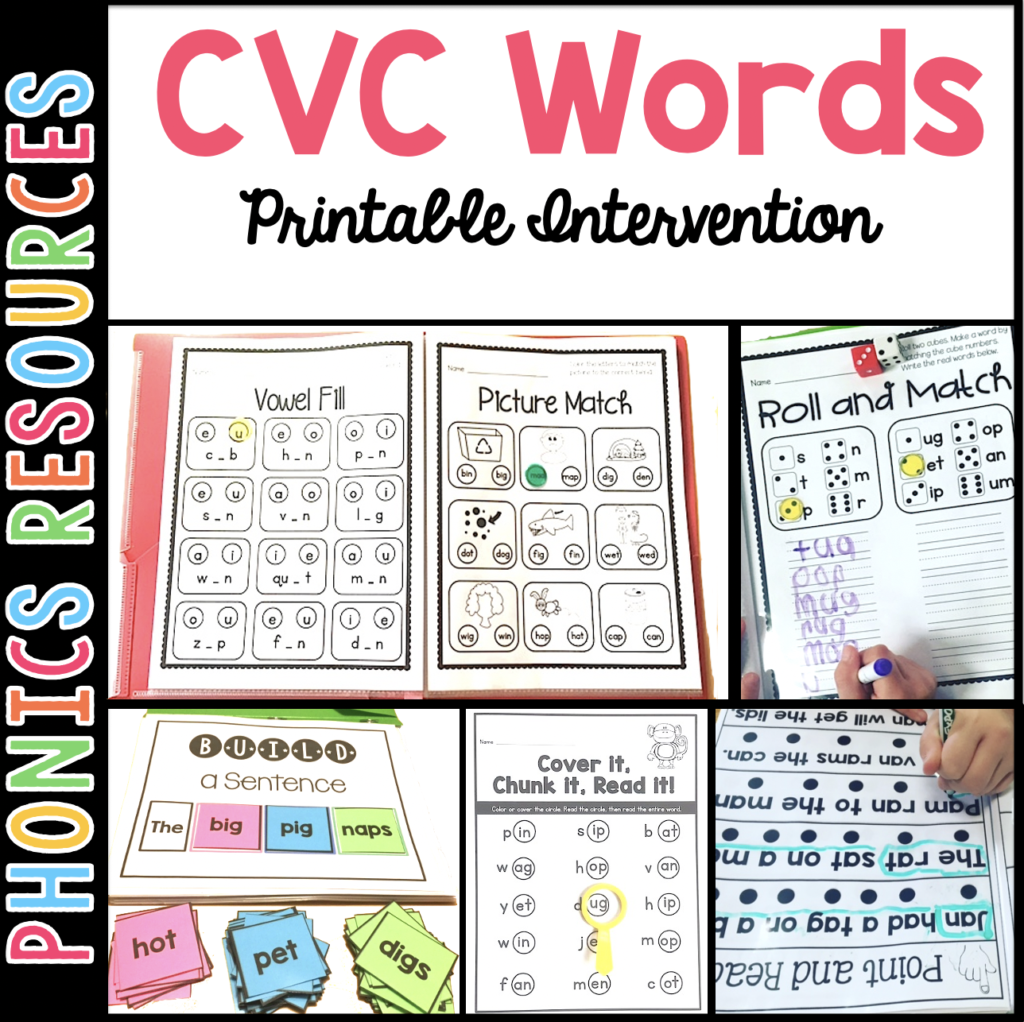

I also have several printable intervention packs, like the one shown below. Click here to get to those.

Digital Resources

I have several Boom decks for word building including cvc words, digraphs, consonant blends, silent e, vowel teams, ck words, bossy r, and diphthongs. I set these up to be like sound boxes. With this resource, students can tap the picture to hear the word, then they drag the letters to the empty boxes to spell the word. These are self-checking, which is great because then students can try again if they make an error.

Click HERE to see all of the digital word building decks.